Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog (1999): Criterion Blu-ray review

Jim Jarmusch, like his near contemporary David Lynch, came to film obliquely and has produced a distinctive, idiosyncratic body of work which reflects but steadfastly refuses to adhere to the models of the commercial mainstream. While Lynch began as a painter and sculptor, Jarmusch initially set out to be a poet, getting a BA in English at Columbia before taking up cinema. Having been exposed to a broad variety of films at the Cinematheque Francaise during an extended stay in Paris, he attended a film program at NYU where, in his final year, he became assistant to Nicholas Ray, who was teaching at the school and also working with Wim Wenders on the personal documentary Lightning Over Water (1980) about Ray’s final years as he fought terminal cancer.

By the time Jarmusch set out to make his own ultra-low-budget first feature, Permanent Vacation (1980), he was steeped in literature, music and the counter-culture, resulting in a rough punk aesthetic. That film drew on many of the connections he had made at film school and on the music scene – Sara Driver, Tom DiCillo and, crucially, John Lurie. But it was four years later, with those same collaborators, that Jarmusch really found his cinematic voice. His second feature, Stranger Than Paradise (1984), also made for very little money, was a critical and festival hit, garnering numerous awards in multiple countries; it was also a modest commercial success.

Stranger Than Paradise established many of the key elements of Jarmusch’s distinctive style. Its attention to the minutiae of human behaviour, its narrative ellipses, its refusal to offer the conventions of mainstream storytelling while providing other, unexpected satisfactions. With assurance, Jarmusch was training his audience to look at the world differently – each scene is a single shot taken from a fixed camera position, the characters moving in and out of frame, clashing in ways which trigger a constant stream of small recognitions. The trio of characters, friends who banter, irritate and confound one another, behave not like characters in a story, but rather like people getting on with their aimless lives.

The film also established what would become a familiar structure more akin to the movements of a musical composition than a three-act drama, built from rhymes and repetitions and counterpoint. Stranger Than Paradise and the two films which followed, Down By Law (1988) and Mystery Train (1989), use this three-part composition, while his fourth feature, Night On Earth (1991), expanded it to five parts. But even as the films got bigger and more complex, they retained that narrative obliqueness and fascination with seemingly extraneous details.

Jarmusch was sometimes dismissed as being too self-consciously cool, a hipster playing at movies, but that accusation misses not only the richness of his characters – and his obvious deep affection for them, an embrace of both their virtues and their flaws – but also his exploration and critique of the various genres which make up so much of mainstream cinema. His method was often to embed those characters in a familiar form and then strip away the rigid superstructure of genre. Down By Law is a prison break movie, but we never actually see how the three characters break out. What’s important to Jarmusch is the ways in which the three men, so unlike one another, play off each other as they go on the run and hide out. Every time I see the film, I find myself not liking the characters in the first movement as they are each introduced separately, but once they are together in jail and even more so after their escape, they begin to emerge from their original solipsistic egoism and become social creatures whose interactions generate increasing emotional warmth.

Jarmusch made a quantum leap with his sixth feature, Dead Man (1995), which took on not simply the western genre, but the whole sweep of mid-19th Century American history, the intersection of Manifest Destiny and industrial development with the wilderness and indigenous peoples which westward expansion was steadily erasing. Jarmusch wove so many threads into a superficially familiar narrative – a man on the run through the wilderness pursued by bounty hunters – that the film becomes a richly layered meditation on the genocidal inevitability of white society’s expropriation of the continent through violence. The vehicle for this meditation is a character antithetical to the classical western hero (or villain), a hapless accountant who is essentially already dead (hence the title), carrying a bullet in his heart but stubbornly refusing to lie down and give up. Even more important in some ways is the companion he finds along the way, a Native American named Nobody (Gary Farmer) who is caught between native and white worlds, observing conquest and resistance from an untenable position between those two overwhelming historical and cultural forces.

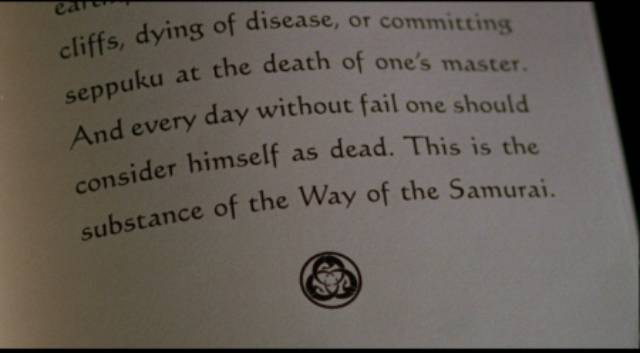

In his seventh feature, Jarmusch expanded on many of these themes and brought them into a contemporary world, a world in which Manifest Destiny had long-since fulfilled its purpose. Wilderness has been replaced by urban expanses falling into decay, and many of this world’s inhabitants have lost their sense of purpose. Like Dead Man’s William Blake, the protagonist of Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999) is already a dead man, but he clings to life by adhering to the code of loyalty defined by the 18th Century practical and spiritual guide Hagakure compiled by Yamamoto Tsunetomo, which sets out the nature and responsibilities of the Samurai, a warrior-retainer to a master to whom he owes everything, including his life.

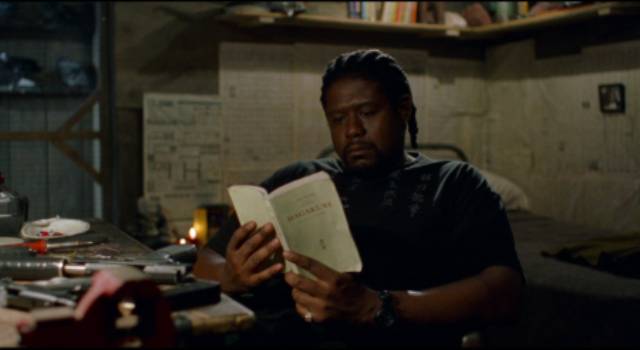

Ghost Dog (Forest Whitaker) takes his role very seriously even though his master is not exactly worthy of his devotion. Louie (John Tormey) is a low-level mafioso in the Vargo crime family, who some years ago saved Ghost Dog’s life in a back alley; in debt to Louie for this, Ghost Dog became his “retainer”, performing a series of hits efficiently and without question. Being a “dead man” has endowed Ghost Dog with an almost mystical presence – as he walks down the street he goes unnoticed by those he passes. Between jobs, he lives in a rooftop hovel and tends a flock of pigeons, taking pleasure in their flight and communicating with Louie by sending bird-borne messages.

His latest contract is a member of the family who has unwisely started an affair with the boss’s young daughter Louise (Tricia Vessey). Things go wrong because Louise was supposed to be on a bus out of town, but she’s there in the room when Ghost Dog makes the hit. He doesn’t kill her because she’s not part of the contract and she gives him the book she was reading, Rashomon and Other Tales by Akutagawa. This is one of a number of books explicitly referenced throughout the film, along with the Hagakure.

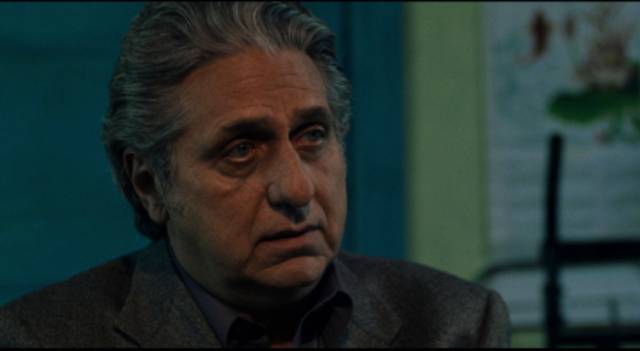

Because Louise witnessed the killing, boss Ray Vargo (Henry Silva) orders that Ghost Dog be eliminated, despite Louie’s insistence that he’s a valuable asset. As genre convention would have it, when Ghost Dog is targeted he sets out to fight back by killing all the members of the family except Louie and Louise. But his sense of honour ultimately brings about his own end – the death forestalled by Louie in that back alley finally catches up with him and he accepts it willingly as the inevitable self-sacrifice of the Samurai fulfilling the role defined by the code.

But none of this plays out with the narrative momentum of a typical gangster movie. As always, Jarmusch is more interested in the narrative interstices, the odd tangential bits of behaviour which illuminate character. Ghost Dog’s best friend is a Haitian immigrant who has an ice cream truck parked in the neighbourhood. Raymond (Isaach De Bankolé) speaks only French while Ghost Dog speaks only English and yet they each understand what the other is saying, sharing a harmony beyond language. While Ghost Dog is a centre of stillness, silent and contained, Raymond is effusively outgoing, brimming with life.

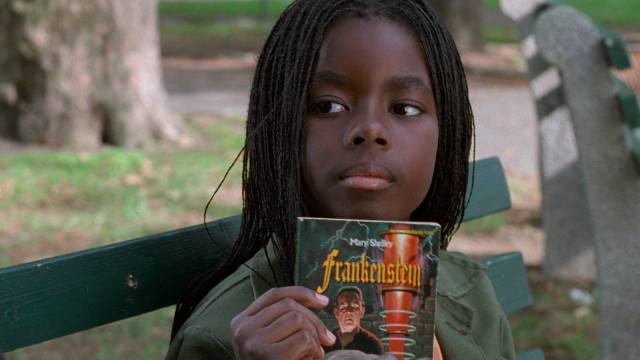

While sitting on a park bench, Ghost Dog listens to a group of freestyle rappers whose lyrics seem to comment on his situation. A young girl, Pearline (Camille Winbush), sits down and starts to talk to him. Like him, she’s dressed in fatigues. Like him, always carrying his briefcase filled with the lethal tools of his trade, she always carries a colourful lunchbox filled with the books she reads – Frankenstein (they agree that it’s “better than the movie”), The Wind in the Willows, W.E.B. Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk. He gives her Rashomon and asks her to come back and tell him what she thinks. When she does, they both declare “In the Grove” their favourite story, the one in which a single event is seen very differently by the three characters involved. This is echoed in the film when we see two different versions of that back alley scene in flashbacks from both Ghost Dog’s and Louie’s perspective: Louie recalls that when he interrupted the beating, one of the gang turned a gun on him, thus he inadvertently saved Ghost Dog’s life in protecting himself, while Ghost Dog remembers the gang member’s gun pointed at his own head. For Ghost Dog, Louie saved him from imminent death, necessitating the payment of a debt through loyalty, while for Louie his bond with Ghost Dog is much less consequential.

This imbalance is crucial to one of the film’s main themes. Ghost Dog has dug far into the past to find a code to which he adheres with unwavering commitment, but the family to which Louie belongs has largely forgotten its own code. Ghost Dog is a tragic character, his story a tragedy – adhering to the code of the Samurai, committed to serving an unworthy master, leads inevitably to his own destruction… But this being a Jarmusch film, the tragedy is counterbalanced by comedy in the form of the Vargo family, ageing, unhealthy gangsters who go through gangster motions, remembering that they had their own code but no longer having any real sense of what it’s for. They hang out in their clubhouse behind a Chinese restaurant, owing rent, threatened with eviction; they play cards and read newspapers. Vargo himself watches old cartoons on TV, staring intently at the absurd reality-defying antics of Betty Boop, Felix the Cat, even The Simpsons’ Itchy and Scratchy, as if they hold some important clue – and in a way they do, as they reflect on and prefigure what Ghost Dog does and what happens to him. But this gang doesn’t actually seem to be doing much crime any more, except for senseless killings in the name of “honour”. Their code is mere habit, its meaning and purpose forgotten…

What’s remarkable about Jarmusch is the way he manages to combine Ghost Dog’s dark narrative trajectory with the ensemble comedy of the gang – a collection of wonderfully talented actors led by Henry Silva and Cliff Gorman – into something complex yet unified, an elegy to a lost sense of honour in a morally corrupt world. When Cliff Gorman breaks out into rap at the meeting where Louie is ordered to eliminate Ghost Dog, it seems both ridiculous and natural, a moment which ties these out-of-date gangsters unselfconsciously to the world of the man they’re condemning. Later, Gorman sings rap and dances ecstatically the moment before he dies – the blending of cultural cross-currents is not enough to keep these characters from destroying one another.

The possibility of a world in which these fatal conflicts might be neutralized is suggested by the chain of literary exchange which flows through Ghost Dog. History, philosophy, spirituality and storytelling itself are transmitted via him from Louise to Pearline and back, and even on to Louie, who seems incapable of comprehending them. In the end, it’s the two female characters who seem to understand what Ghost Dog’s life means, but they come away with contradictory conclusions which will only continue rather than bring an end to the destructive cycle of violence.

Jarmusch’s work is observant and exploratory rather than predetermined and declaratory; he doesn’t so much tell a story as allow a story to emerge from character and situation … and what emerges in Ghost Dog, as in Dead Man, is so rich and far-reaching that it gives the lie to that facile image of Jarmusch as nothing more than a cool hipster. He is, rather, one of the masters of independent filmmaking, an artist who reshapes the terrain of popular cinema to change the way his audience sees what they have come to take for granted. What is familiar becomes in his hands unfamiliar and produces a simultaneous shock of recognition and revelation.

*

The disk

Criterion’s 4K restoration is a big improvement over the old Artisan DVD, with improved colour and contrast providing a film-like image rich in detail.

The supplements

There are more than three hours of new and archival extras, with a certain amount of repetition as several featurettes make use of the same interviews with Jarmusch, Whitaker and the RZA (who contributed the eclectic, evocative score) from 1999 – these cover Jarmusch’s writing process, his work with the actors, and the evolution of the music (15:08, 21:30, 14:47). There’s a brief interview with martial arts master Shifu Shi Yan Ming (5:37), something of a spiritual mentor to Jarmusch, who has a brief appearance in the film, and another with casting director Ellen Lewis (15:32).

There’s also a brief collection of deleted scenes and outtakes (5:25) and a trailer (1:06).

The most substantial extras are a three-way conversation (29:57) between Whitaker, co-star Isaach De Bankolé and Michael B. Gillespie, who discuss the making of the film, Jarmusch’s process as writer and director, and the cultural implications of the film’s mix of genres; and a Q&A (1:24:08) in which Jarmusch answers questions submitted to Criterion by fans from around the world (similar to the one on Criterion’s Dead Man Blu-ray). This is casual and discursive, prompting memories and observations which stray from the movie itself into Jarmusch’s thoughts about life, philosophy, art and music, revealing him to be a thoughtful and self-aware artist.

The booklet includes essays by critics Jonathan Rosenbaum and Greg Tate, an interview with Jarmusch from the time of the film’s release, and the aphorisms from the Hagakure which are quoted in the movie.

Comments