Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man (1995): Criterion Blu-ray review

The idea that death is a journey was common in pre-modern societies; it was a crossing of boundaries, often involving tests and obstacles, even the paying of a price to guardians at the border. This mythology is the essence of Jim Jarmusch’s sixth – best and most complex – feature, Dead Man (1995). The personal story of an unexceptional man making that journey, the film also embodies larger themes about the transition from a pre-industrial to an industrial world, and about the consequences of Manifest Destiny in the formation of the United States.

In a prologue set on a train heading west, accountant William Blake (Johnny Depp) drifts in and out of sleep, at each waking finding himself surrounded by harsher, less developed fellow passengers. The film’s first dialogue comes as the train’s fireman (Crispin Glover) comes back and sits facing Blake, asking personal questions and making cryptic remarks. We learn that Blake is heading from Cleveland to a town called Machine, where a job awaits him at the Dickinson Metal Works. We also learn that his trip has been delayed by the death of his parents; that his fiancee has broken off their relationship. Already, he is leaving behind an entire life, heading towards something unknown. While this suggests the central American myth of regeneration and second chances, in the event it becomes something much darker.

Through the train’s windows, Blake sees vast empty landscapes, occasional signs of human presence, though these are already abandoned. The prologue ends with the rough-hewn passengers suddenly blasting through the windows with their big rifles, senselessly slaughtering buffalo just for the fun of it. These white men bring death with them into the wilderness and when the train finally arrives in Machine (“the end of the line,” the fireman emphasizes) the town is steeped in death and hopelessness, piles of animal skins and mounds of bones, walls decorated with countless skulls, empty-eyed people staring at the stranger walking along the muddy street, his bright plaid suit ridiculously out of place.

Passing through the arched gate of the Dickinson Metal Works, Blake is entering a vision of Hell filled with grimy men enslaved to pounding machines, surrounded by fire and smoke and steam (here Jarmusch seems to be channeling David Lynch, the phantasmagoric imagery combined with menacing industrial sounds which evoke memories of Eraserhead and The Elephant Man). In the company office, Blake is met with contempt and ridicule by the chief clerk (John Hurt) who tells him he’s too late, the job has gone to another man. Desperate, all his money spent on the trip, Blake insists on seeing the owner; the staff laugh derisively, but he is pointed towards the door to an inner office.

Inside, he faces a life-size portrait of John Dickinson behind a desk on which sits a human skull, a huge taxidermied bear looming in a corner, teeth and claws bared. Turning back from the bear, Blake finds Dickinson (Robert Mitchum) pointing a shotgun at him and demanding to know what the hell he’s doing here. Blake tries to explain, but the cigar-chomping industrialist isn’t interested; Blake beats a hasty retreat and almost gets lost in the factory before he finds his way back to the muddy street and a saloon, where he spends his last few coins on a bottle of whisky.

Outside the saloon, he sees a young woman named Thel (Mili Avital), a seller of paper flowers, tossed out into the mud; he helps her up and she takes him back to her room. For a brief, gently romantic moment, he can forget the nightmare situation he’s landed in. But then Thel’s former lover Charlie (Gabriel Byrne) arrives to find them in bed together; she tells him to get out and he draws a gun. Thel throws herself in front of Blake and the bullet passes through her and into his chest. He fumbles with the gun she keeps under her pillow and shoots Charlie; Blake grabs his things and dives out the window, stealing Charlie’s horse and riding away.

With a bullet lodged by his heart, Blake is now the dead man of the title, hovering between worlds. In the woods beyond the town, he meets his spirit guide for the journey, an Indian who tries but fails to dig the bullet out with a knife. This is Nobody (Gary Farmer). It’s immediately apparent that Nobody is more cultured than Blake; when he learns Blake’s name, he is startled – “you are indeed a dead man” – and quotes lines from Blake’s “Auguries of Innocence”, puzzled that this man has forgotten his own poetry.

Nobody is himself a man caught between worlds, belonging nowhere. As a boy, with parents from two tribes which were hostile to each other, he was an outsider, left to fend for himself. He was captured by British soldiers, put in a cage and sent East, moving from city to city and then crossing the ocean. In England, he took advantage of his status as an exotic exhibit and gained an education, discovering the poetry of Blake which reflected and echoed his own indigenous view of the world. He brought this experience and the knowledge he had gained with him when he escaped back to America, but his people didn’t believe any of it, mocking him as “he who speaks much but says nothing”. But now he’s found this William Blake and he takes it on himself to guide the “dead man” to the far western shore of the land and set him on his journey beyond the ocean’s horizon.

The film continues as a dreamlike stream of vignettes and episodes as Blake and Nobody pass through spectacular natural landscapes, the world destined to be swept away by the westward expansion of European “civilization” and industry. And their passage brings death with them, both in the form of a trio of bounty hunters hired by John Dickinson to avenge the death of his son Charlie, and as a kind of contagion being carried by Blake himself. Everyone they meet dies a violent death, even as Blake acquires a kind of serenity in acceptance of his fate.

Dead Man is remarkable in a number of ways, not least in having been written and directed by Jim Jarmusch, whose other work is quintessentially urban and contemporary. Here he transforms familiar western tropes into a contemplative epic poem on the inherent destructiveness of “progress”, a relentless process which consumes the natural world and leaves filth and wreckage in its wake. But it’s more complicated than that. Nobody, displaced by this process, has absorbed the best of the invading “civilization”; he has appropriated the alien culture, and while this has separated him from his own origins, it has deepened and enriched his understanding and equipped him to guide Blake through the natural world towards a more spiritual state.

The narrative alternates rhythmically between Blake and Nobody on their journey towards greater understanding and the pursuing bounty hunters, who learn nothing and ultimately – and literally – consume themselves in their hostility to life. What Jarmusch brings to this world from his previous work is his wonderful eye for the idiosyncrasies of behaviour and his ear for oblique, allusive speech laced with wit. For all its rich visual imagery and dark themes, Dead Man is often very funny, particularly in Nobody’s exasperated disdain for the behaviour of “stupid fucking white men”, but also in the interactions between the bounty hunters. The taciturn, quietly deadly Cole Wilson (Lance Henriksen) does an extended slow burn through much of the film as Conway Twill (Michael Wincott) never stops talking, spewing an endless stream of meaningless trivialities, the two of them observed by the ambitious kid (Eugene Byrd) who rides with them hoping to make a name for himself as a killer.

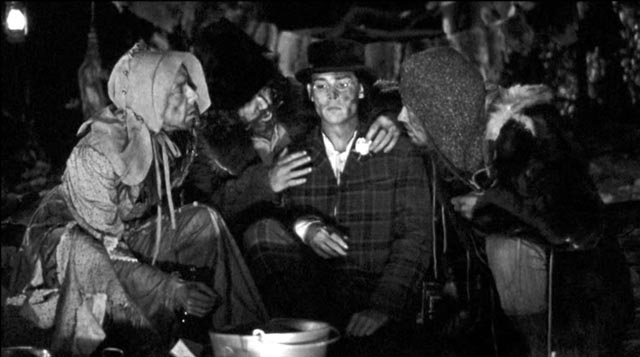

Jarmusch has always had a flair for casting, but Dead Man is perhaps his richest work in this respect, with every role no matter how small populated by distinct and quirky performers. Though each gets only a small amount of screen time relative to Blake and Nobody and Wilson and Twill, they all stand out as figures who evoke entire lives in fragmentary moments (often at the point of sudden death): Robert Mitchum in one of his final roles as the monstrous industrialist, John Hurt as his head clerk, Gabriel Byrne as his son, a disappointed lover; Mili Avital is gently romantic as a woman doomed by a place hostile to both romance and life itself, while Alfred Molina is a frontier storekeeper contemptuous of the native population, willing to sell them disease and death. There’s a strange encounter with a trio of men camped in the woods at night, Billy Bob Thornton, Jared Harris and Iggy Pop (dressed in woman’s clothes), all speaking in strangely formal language as they plan to rape and kill Blake. Finally, it’s interesting to note just how good Johnny Depp is in the tricky role of what is essentially a passive, almost inexpressive character; it’s a subtle performance which anchors the entire film, a far cry from the cartoonish self-parody he has since descended into.

Eventually, and inevitably, the journey approaches its end with a trip down a river, Blake barely clinging to life, finally reaching a native village on the Pacific Northwest coast, with great decorated wooden halls which echo the streets of Machine, but also contrast with that hell-hole by seeming to grow organically out of the forest. Here Nobody enlists aid and acquires a sea-going canoe into which he lays Blake, pushing him out into the surf; the film ends with an image of the boat disappearing towards the distant ocean horizon, carrying Blake towards a spirit world in which he has already half lived during the long journey.

Steeped in death, Dead Man is nonetheless an elegiac tone poem which asserts a continued spiritual existence against the crushing materiality of the world. Jarmusch is aided in his project by two crucial collaborators: cinematographer Robbie Müller, whose exceptional work for Wim Wenders, Lars von Trier and Jarmusch himself (previously on Down By Law and Mystery Train) was never more impressive than here. Shot in luminous black-and-white, the film recalls the look of classic Hollywood westerns while adding something new, that sense of something immaterial suffusing the landscapes through which the characters pass.

Just as important is the unconventional score composed and performed by Neil Young. While at first glance it would seem inappropriate to use solo electric guitar for a film so richly textured with period detail, Young responds emotionally to the rhythms of the imagery – the music was recorded live over a couple of days, with Young surrounded by his various instruments in a warehouse where the film played on multiple monitors uninterrupted; he watched and responded in real time, projecting his own emotional responses through his instruments. The music is so organically wedded to the images that it’s impossible to imagine Dead Man with any other score.

*

The disk

Criterion’s Blu-ray is mastered from a 4K transfer from the original camera negative and the imagery virtually glows. The amount of detail visible in both town and mountain forests gives the film a tactile quality which reinforces its thematic concerns, while the uncompressed sound reveals the subtle interaction between human voices, natural (and industrial) ambiences, and Neil Young’s textured music.

The supplements

Although it initially seems odd that Jarmusch is absent from the commentary track, production designer Bob Ziembicki and sound mixer Drew Kunin provide a great deal of detail about the production – both from a technical standpoint and also in terms of theme and narrative.

In lieu of a director’s commentary, Jarmusch is present on the disk in an audio Q&A played over an image from the film (47:42). Here he responds to questions submitted to Criterion by fans of the film. There’s an odd, random quality, with some questions unconnected with Dead Man specifically; but they provide Jarmusch with an opportunity to riff on his creative process in sometimes illuminating ways.

There’s an interview with Gary Farmer (26:47), who talks about the treatment of native Americans in the movies and his relationship with Jarmusch on the project.

Seven deleted scenes (14:59) in lower resolution are interesting, but don’t add anything crucial to the film.

Three members of the cast – Iggy Pop, Alfred Molina and Mili Avital – read excerpts from Blake’s poetry over a selection of Jarmusch’s location-scouting photos (7:30).

There is also a gallery of fifty colour photos from the production which provide an interesting contrast with the black-and-white cinematography.

Finally, the disk includes a trailer (2:37).

The booklet contains essays by film critic Amy Taubin and music journalist Ben Ratliff.

Comments

I like Jim’s pictures but I find I rarely get back to them. Usually a couple of watches are enough. Perhaps not enough time has past. Of course, there’s so many new DVDs coming in that I can’t find the time to watch the older DVDs.

I have the same problem. I have so many unwatched disks in my collection now that even if I stopped buying new ones altogether I’d be dead long before I got through them all.

Hi there,

thanks for the review. Is there a chance to post screenshots of the fan questions? I’m curious because I sent a question and would like to find out if it was answered.

Greetings from Germany!

Hi. This is an audio-only feature, so no names are shown on screen.