Exiles at war

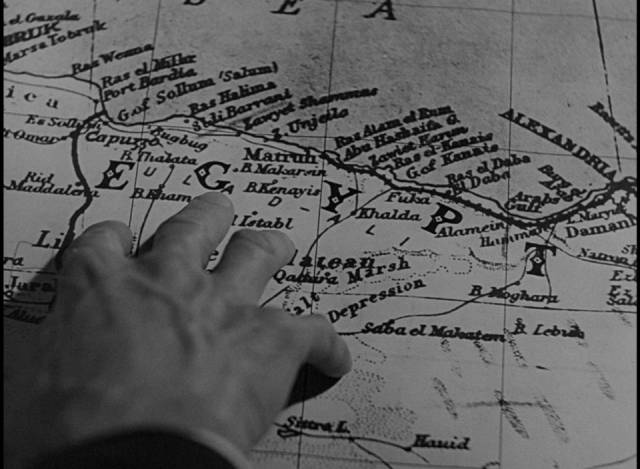

Cpl. John Bramble (Franchot Tone) stranded in the desert after a battle in Billy Wilder’s Five Graves to Cairo (1943)

With Hollywood geared up to provide uplifting propaganda for the home front audience after the U.S. entered the war at the end of 1941, did German exile filmmakers find themselves in an odd position? Directors like Fritz Lang and Billy Wilder were obviously anti-Nazi, but the industry had exercised restraint for years because Germany remained a profitable export market and the studios definitely didn’t want to alienate Hitler’s government. (Thomas Doherty provides a fascinating account of this period in his 2013 book Hollywood and Hitler 1933-1939.) There were multiple currents at work, particularly concerns about Communist influence as the nation struggled to emerge from the Depression, which created the odd category of “premature anti-Fascism”; although once the war began Fascism was the unequivocal enemy and the U.S. became allied with Stalin’s Russia, those who opposed Hitler in previous years were distrusted and many eventually fell to the Red-baiting hysteria of the post-war years.

Fritz Lang nonetheless got an early start with the release of Man Hunt (1941) six months before Pearl Harbor. Approaching the current conflict obliquely, setting its cat-and-mouse story in the late 1930s when a British big game hunter, just for sport, gets close enough to Hitler to assassinate him, although he has no intention of pulling the trigger. It’s an absurd premise, but sets in motion an espionage tale which reveals the threat the Nazis pose to unprepared democracies. In retrospect, it can be seen as both a popular entertainment and a deliberate element in the growing effort to prepare the American public for the necessity of joining the war.

By 1943, with the war at his height and the defeat of Germany by no means a certainty, it was possible to tackle the conflict head-on in Hangmen Also Die!, a rousing fictional account of the assassination by Czech partisans of Reinhard Heydrich, one of the main architects of the Holocaust and Reichsprotektor of occupied Czechoslovakia. By this point, there were no qualms about depicting the Nazis as morally corrupt monsters whose destruction warranted the high cost paid by the Czech people for this assassination.

A year later, with the war turning in the Allies favour, Lang could make Ministry of Fear (1944), an entertainment based on a Graham Greene thriller, in which a troubled hero inadvertently stumbles into a plot by Nazi spies. This was more like one of Hitchcock’s 1930s adventures than an urgent exercise in propaganda. But after the war, with the release of Cloak and Dagger (1946) just a year after the defeat of Japan, Lang was already using the spy genre to look ahead at the new threat of atomic weapons, although the story was set a year or two in the past.

*

Cloak and Dagger (Fritz Lang, 1946)

Scientist Alvah Jesper (an awkward Gary Cooper) is visited by an old friend who is now working for the OSS. Both men are involved in secretive work – Jesper as part of the massive project to develop the atom bomb, his friend coordinating espionage missions in enemy territory. The friend wants to recruit Jesper to help get a top scientist out of Europe – Katerin Lodor (Helene Thimig) has been unwillingly involved in the Nazis’ own nuclear program and is now sick in a Swiss hospital. The OSS need Jesper to convince her to come to the States because his own stature as a scientist will give credibility to the proposal.

That plan goes wrong, partly because of Jesper’s inexperience, and Lodor is killed by the Nazis. This changes the mission; now Jesper must go to Italy to try to persuade another reluctant scientist, Polda (Vladimir Sokoloff) to defect. With the help of a group of Italian partisans, including Gina (Lilli Palmer), who initially resists the American but eventually becomes a half-hearted love interest, Jesper contacts Polda who has been forced to work for the Nazis because they have his daughter as a hostage. Again things don’t go according to plan, with many partisans sacrificed in order to get Jesper and Polda away by plane, although it’s unclear whether the Italian will survive.

Cloak and Dagger is an oddly ragged film for Lang, never quite coming together, not least because of a miscast lead – Cooper isn’t very convincing as a nuclear physicist and his abrupt transformation from academic to man of action is even less convincing; he fumbles things in Switzerland, and yet in a taut montage skilfully traps a German double agent into helping him as if he’s been doing this spy stuff for years. Although Lilli Palmer is very good as Gina, serving as the symbol of those who risk everything to fight the insidious enemy, she ends up in the generic position of romantic object complete with a clumsy farewell too obviously modelled on Casablanca but without the long emotional build-up which makes that film’s climax so satisfying. In Lang’s film the couple’s farewell is an irritating obstacle which delays the obviously urgent departure of the plane.

But what really cripples the film is the fact that it doesn’t follow through on its main theme, established in that opening scene between Jesper and the OSS man. Jesper has an impassioned monologue there in which he asserts the danger of the new weapons he has helped to create – the Nazis may be facing defeat, but the Allies have built something even more dangerous in their effort to win the war, something which will inevitably be beyond anyone’s ability to control. Released just a year after the bombs were dropped on Japan, Lang and his scriptwriters Albert Maltz and Ring Lardner Jr (both soon to run afoul of the House Committee on Un-American Activities as members of the Hollywood Ten) were already looking ahead to the Cold War and the threat of nuclear annihilation.

And that was a problem. The script hadn’t ended with Jesper’s escape, but with an extended coda in which an attack on one of the Nazis’ own research facilities failed to eliminate their program, all the equipment and personnel having been spirited away, perhaps to South America, where the threat would continue. But that ending was cut off before the film’s release (and apparently destroyed), possibly due to government interference, or at least by a producer who feared such interference, because it cast a negative light on the whole idea of atomic weapons and atomic energy, which was officially being pushed by the authorities as a great boon to the country in the post-war world.

But while Cloak and Dagger falls short as one of Lang’s spy films (a genre he pretty much invented and gave all its key attributes in a series of films from 1928’s Spione to 1960’s The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse), it does have some excellent sequences – that montage in which Jesper traps the double agent; the failed attempt to rescue Professor Lodor; Jesper’s audacious visit to Professor Polda right under the noses of his Nazi guardians. But the real standout is the sequence in which Jesper is forced to dispose of a Fascist agent (Marc Lawrence) in the lobby of a building which is open to the busy street. This is a protracted and extremely brutal fight which surely must have stood as the model for the equally painful farmhouse murder which itself was the best sequence in Alfred Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain (1966). Few studio movies of the time treated violence with such realism.

*

Five Graves to Cairo (Billy Wilder, 1943)

Fritz Lang, even in his lighter entertainments, can’t be said to have had a sense of humour, something definitely not true of his fellow exile Billy Wilder, who even in his darkest, most serious movies displayed a lightness of touch and sharp wit. Having established himself as a scriptwriter in the ’30s, beginning with People on Sunday (1930) and peaking with Ninotchka (1939), he began directing in the early ’40s with a comedy, The Major and the Minor (1942), and very quickly ascended to the Hollywood heights with the quintessential noir Double Indemnity (1944), nominated for multiple Oscars, and The Lost Weekend (1945), which won him the first of two Best Director Academy Awards.

Given his stature, it seems odd that his second feature isn’t better known. Five Graves to Cairo (1943), a thriller set in the North African desert not long after the events which give the story its context, manages to avoid much of the stereotyping and cliches to which propaganda movies were prone. In some ways it’s very similar to Michael Curtiz’ Casablanca, though its potential for romance is kept in check by a harder edge of realism beneath the adventure story.

The film, adapted by Wilder and writing partner Charles Brackett from a World War One play by Hungarian author Lajos Biro, is an intricately plotted story of hidden motives, concealed identities, and ordinary lives caught up in sweeping events. Apart from a haunting opening sequence in which a British tank rolls across the dunes carrying a dead crew, with one man regaining consciousness in time to avoid succumbing to the exhaust fumes filling the vehicle, all the action takes place inside the partially ruined Empress of Britain hotel. The sole survivor from the tank, Corporal John Bramble (Franchot Tone), staggers out of the desert in a state of delirium and enters the hotel believing it’s company headquarters. There are only two people there, the owner Farid (Akim Tamiroff) and the French maid Mouche (Anne Baxter).

Bramble passes out in the lobby just as a German advance party arrives, intending to use the hotel as a base as the army advances into Egypt, pushing the retreating Allies towards Cairo. With no other option, Farid drags Bramble behind the small reception desk and in the first of many tense sequences has to distract the officer in charge, Lieutenant Schwegler (Peter van Eyck), before he can see the British soldier. Bramble comes to during this and, realizing his precarious situation, manages to slip out without being seen, much to Farid’s relief.

But that relief doesn’t last long; as the Germans take over the hotel, Farid and Mouche discover that Bramble has slipped back in and is in the office upstairs changing out of his uniform and into the clothes of the waiter, Davos, who died in a recent air raid. Awkwardly, Farid has already told Schwegler that the waiter is dead and Bramble has to quickly convince the officer that he had only been buried alive and had just managed to dig himself out. He gets an odd look from the German which is quickly explained when Field Marshall Erwin Rommel arrives and Bramble discovers that Davos was in fact a German agent who had been passing crucial information to Rommel’s forces about the British who had been based at the hotel.

Bramble, who had at first seen an opportunity to assassinate Rommel, quickly changes plans because it becomes apparent that there is some secret behind the rapid advance of the Germans; if he can obtain that information and get it back to the British in Cairo, perhaps the tide can be turned. Expecting assistance from Farid and Mouche, Bramble discovers that the French woman is hostile to the English because they had abandoned the French at Dunkirk and she lost one brother there, while another was taken prisoner. Bramble’s presence endangers her own plans to try to get Rommel to arrange for the release of her sick brother.

Wilder weaves these multiple threads together with precision, building narrative suspense while creating complex character relationships which are often rooted in deceit. The setting, the suspense, the mixture of wit and high stakes danger all reminded me of King Hu’s “Inn” films – Come Drink With Me (1966), Dragon Gate Inn (1967), The Fate of Lee Khan (1973). But one of the most interesting aspects of Five Graves to Cairo is the treatment of the Germans. For a film made in 1943, it seems surprising that they aren’t grossly caricatured, but rather are treated with the same interest as the “good guys” – all flawed characters caught up in a conflict larger than themselves and taking advantage of circumstances to further their own interests.

Although Schwegler is an opportunist who lies to Mouche in order to seduce her, his actions are not those of an inhuman monster, but rather those of an amoral jerk. But his boss, Rommel, is a cultured man made vulnerable by his own massive ego. Wilder is helped here by the casting of the great director Erich von Stroheim, Hollywood’s go-to choice for Nazis at the time. The Field Martial has enormous charm as he entertains a group of British officers who have been taken prisoner, his pride in his own skills leading him to reveal a bit too much about his plans, giving Bramble sufficient clues to deduce how the German advance has been so successful.

Wilder ratchets up the tension as an air raid drives everyone into the cellar where a bomb exposes the body of the real Davos, seen only by Schwegler, leading to a desperate fight which puts Mouche in danger even as it paves the way for Bramble to get the crucial information back to the British.

Although this was just Wilder’s second directorial effort, he has seemingly effortless control over the complex narrative and, just as importantly, over tone. The mix of tension and humour strengthens the dramatic qualities of what might have been a routine exercise in wartime adventure, his empathy for all the characters all the more surprising given that it was made in the midst of the war.

*

Both films look very good on Blu-ray from Masters of Cinema (though reportedly Kino’s edition of Five Graves to Cairo has a stronger transfer). Each film gets a commentary – Adrian Martin on the Wilder, Alexandra Heller-Nicholas on the Lang. There’s a video essay by David Cairns about Lang’s spy films and an archival interview with Wilder about his early films. Each disk includes radio adaptations of the feature, and Cloak and Dagger has all twenty-two half-hour episodes of a radio series about the wartime exploits of the OSS.

Comments