Subverting propaganda:Keisuke Kinoshita and World War II

The West “discovered” Japanese cinema with the appearance of Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon at the Venice Film Festival in 1951 (where it won the Golden Lion as best film, going on to win a special Oscar the following year). Although Kurosawa remained the best-known and most commercially successful Japanese filmmaker for many years, others followed him into the consciousness of Western critics and audiences – Mizoguchi, Naruse, Ozu, Ichikawa, Teshigahara, Kobayashi – and Japanese film became known for sweeping historical epics and intimate family dramas. Many of these films openly critiqued Japanese history and society, the rigid class structure, the samurai code of honour and its mirror image of violent opposition by the dispossessed, while directors like Naruse and Mizoguchi closely observed the often desperate lives of ordinary people struggling to survive. The quiet dramas of these latter directors, and the masterful Yasujiro Ozu, were viewed as the pinnacle of film art, while the samurai films reached a wider popular audience.

The themes of these films, their often dark treatment of Japanese culture, flourished in the years after the Second World War, partly in reaction to the restrictive culture which had preceded (and led to) the defeat of the Japanese Empire. In the decades marked by rising militarism before the war there was strict censorship and finally, in the ’30s, specific directives from the authorities not only about what was permitted, but also what was required – the honouring of martial history and the military, positive portraits of family life; movies had to reinforce the official view of Japanese life in order to prepare the population for the wars which were inevitable as the Empire expanded and clashed with enemies who stood in the way of Japanese hegemony (China, Russia, Britain, the United States).

This aspect of Japanese history has remained somewhat veiled. What we are most familiar with is the more distant past of feudal Japan and the more recent past of the post-war recovery. The war years have been dealt with in films like Ichikawa’s The Burmese Harp, Kobayashi’s The Human Condition, Fukasaku’s Under the Flag of the Rising Sun and documentaries by Imamura and Kazuo Hara among others, but these are critical views from a position of hindsight. Now, however, with the release of their new Eclipse set, Keisuke Kinoshita and World War II, Criterion have provided us with a window on that time before defeat transformed Japan. In these five films, we get a glimpse of Japan from the inside, when the population was required to believe in the near divinity of the Emperor and the infallibility of the military. What is perhaps most interesting about Kinoshita’s films is that they afford us a window into a previously unseen world – the Japanese home front during the war as it saw itself – and illuminates the protracted moment of fracture between the rigid order of a militarized nation and the violent energies which were unleashed after the war’s end.

Keisuke Kinoshita and World War II (1943-46)

Seen in chronological sequence, the five films in the set give a fascinating impression of a slow awakening; but initially, a western viewer must contend with a sometimes visceral response to the films’ propaganda content – for the first four were all made during the war with an ostensible aim to bolster the national spirit. We’re so used to the propaganda produced by our own side during the war that we can largely tune out much of the more dubious content of American and British films of the period – or at least make allowances because of the historical context within which the films were made. But here, we are suddenly seeing those same kinds of attitudes expressed by the other side (although, interestingly, with nothing like the grossly racist overtones of much of Hollywood’s wartime output and with that strange inversion by which killing the enemy seems less important than dying for the Emperor).

Port of Flowers (1943)

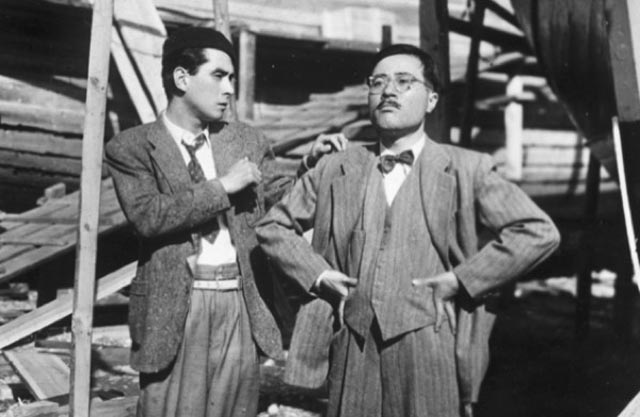

At first, these notes are quite subtle, but they grow more strident over the subsequent films. The first three titles – Port of Flowers (1943), The Living Magoroku (1943) and Jubilation Street (1944) – focus, like so much of Kinoshita’s work (including his masterpiece Twenty-Four Eyes [1954], also available from Criterion), on community. In Port of Flowers, two con men arrive on a remote island, claiming to be the sons of a man who years before had come to establish a ship-building business. That business had failed and the man went away again, though the woman who runs the local inn had loved him and followed him for a while. Declaring that they want to honour their father by going through with his plans, they start fleecing the local population by selling shares. But the younger man is seduced by the quiet life and becomes plagued by conscience. Strangely unable to flee with the money, they initiate the building of a boat. A storm threatens to destroy their work and then, suddenly, war is declared and the completed boat takes on a new importance; an American submarine sinks a local fishing boat, the con men turn themselves over to the local policeman, and the villagers are finally united in a common cause.

Even here, in his debut, Kinoshita demonstrates a fine sense of the expressive possibilities of film, through both camerawork and editing. In particular, there’s a striking moment in a carriage traveling along a country road in which one character relates a past experience to her companions and the rear-projected image seen through the windows dissolves from landscape to city streets, evoking her memories, before fading back to the original landscape. This is moving beyond the general naturalism of the film towards a psychological expression – perhaps a little crude and blatant, but nonetheless a sign of the subtlety which would become a signature characteristic of Kinoshita’s later work.

Until the final moments, Port of Flowers is a charming comedy-drama, with well-observed social details and a variety of engaging characters. The propaganda element comes almost as a surprise, and yet it’s the outbreak of war which resolves all the petty conflicts among the characters and conclusively awakens the conscience of the two crooks. The message is clear: individual concerns have no weight in the face of national crisis … a message already familiar from countless British and American home front movies from the same period.

The Living Magoroku (1943)

The second feature, The Living Magoroku – Kinoshita’s second feature and the only one in the set which he wrote himself – opens with a sweeping 16th Century battle. After the small scale of the first feature, this is really startling. The battle is epic and brutal. With an abrupt cut to the present (as striking in its way as Kubrick’s eons-spanning cut in 2001 and Cimino’s cut from dawn in the Pennsylvania mountains to the fiery chaos of Vietnam in The Deerhunter), we’re introduced to a unit of cadets training on that same field. The field is owned by the Onagi family, whose ancestor fought in the original battle and was awarded the land by his lord. But the bloody history has left a shadow and legend has it that if anyone breaks the ground with a hoe, the Onagi men will die young. The current son is a frightened, neurasthenic who firmly believes that he’s dying. The villagers are restless, insisting that the land should be turned over for cultivation – not simply for their own food production but for the good of the war effort. The family matriarch refuses.

This conflict over the field disrupts a number of lives; clinging to the past is now causing problems for the present. The weight of history on individual and communal lives runs throughout the narrative, symbolized by both the field and a rare sword held by the Onagi family – the Magoroku of the title. A young officer, also a doctor, comes to the family pleading to buy the sword because as a disrespectful youth he had stolen his own family’s Magoroku sword and sold it to get away from home; he now wants to honour his father by restoring that lost family treasure. The matriarch refuses to sell, but the local training officer claims to have one of his own, which may or may not be the one the doctor so rashly sold years before.

The Living Magoroku is about the need to find a balance between honouring the past and tradition and tending to the needs of the present and future. Rigidly clinging to the past causes stasis and a kind of spiritual death, while honouring it and yet moving forward infuses the nation with strength.

Jubilation Street (1944)

In Jubilation Street, Kinoshita moves from the country into Tokyo. The inhabitants of a street which is being appropriated by the government are dealing with the uprooting of their community and the dispersal of families and neighbours. Here, the war is tearing community apart rather than bringing it together and once again there are multiple narrative threads involving individual trials amidst the larger concerns of the war. A new note of melancholy emerges; where before sacrifice for the nation is an unquestioned good, here there is a sense of loss both in terms of the established community being torn apart and on an individual level, with the death of a son whose estranged father has only just returned after years of being away. Despite the need for propagandistic uplift, the reality of the war can no longer be kept at bay.

Army (1944)

That air of sadness makes the film which came after all the more startling. Army (1944) is the most stridently propagandistic in the set, a generations-spanning ode to the militarization of Japan, shot through with historical justifications for the war with the Allies – the Sino-Japanese War, the Russo-Japanese war, western interference with Japan’s imperial ambitions in China. The combination of wounded pride and belligerent ambition is strangely embodied in the story of one family from the mid-19th Century up to the present and a series of sons who are weak and “cowardly” until the glorious military progress of the nation finally imbues the latest boy with the strength and commitment to take on his role as a cog in the fighting machine which is destined to triumph over the Allies who are trying thwart Japan’s rightful ambitions.

Coming towards the end of the war, the propaganda, foregrounded here, seems to have lost much of the previous films’ subtlety. And yet Kinoshita manages to work visually against that pressure to create a counterbalance of critique which apparently was not lost on the authorities when the film was completed. Accused of treason, the director was not permitted to make another film before the end of the war. On its surface, the weight of impending defeat appears to channel all the film’s energies into a single purpose: the futile attempt to convince a national audience that Japan has only been defending herself and that righteousness will guarantee triumph over corrupt enemies. But in its visual strategies, it offers instead a cry of despair at the waste and hopelessness of what the military have forced on the nation. The final wordless sequence highlights the singular pain of a mother watching her son go off to almost certain death … hardly guaranteed to inspire feelings of self-sacrifice in an audience.

Morning for the Osone Family (1946)

Kinoshita’s fifth feature was made the year after the war ended and under the U.S. Occupation. It might not be unreasonable to see in it an effort to placate the victors and apply some reverse-propaganda in an early attempt to undo the effects of the earlier films. (As those earlier films had been made under conditions of strict regulation and censorship, this was made under equally strict conditions imposed by U.S. forces.) But Morning for the Osone Family has a vigour and passion which speaks of conviction. It is also startlingly different from the first four films, not least in the move from community, open air, actual locations to a single set (the Osone family house). The change is signaled immediately as we are introduced to the family in a western-style house as they sing “Silent Night” at Christmas 1943, indicating that they are part of Japan’s Christian minority – outsiders. As the piano-playing Akira Minari prepares to go off to war, he hands his fiance Yuko a letter which she is to read after he leaves. As she reads that he is breaking off their engagement, police arrive and arrest son Ichiro for subversion because he has written against the war.

Taiji, the second son, an artist, is drafted. Rather than accepting the great honour of being offered the chance to die for the Emperor, he gets drunk and submits with deep bitterness. Uncle Issei, a colonel in the army, is appalled at what he perceives as weakness engendered by liberal ideas instilled by his dead brother, blaming Fusako, the mother, for not imposing a harsher discipline on her children. It was he who broke off the engagement with Minari because he couldn’t countenance the son of a wealthy family being tied to the sister of a radical like Ichiro. Instead, he determines to arrange a “more suitable” marriage for Yuko. As the war draws closer to Japan and the cities are bombed, Issei and his wife are displaced, moving into the house and taking control of the family. Issei fills the younger son, Takashi, with militaristic ideas, encouraging the boy to enlist against his mother’s wishes. Issei represents the whole military establishment which drove Japan to war, but his jingoistic pronouncements – offered in the earlier films as fortifying ideas – are now seen as corrupt and destructive. When the war ends, with two sons dead, while blustering about the betrayal of the politicians, Uncle Issei uses his position and connections to steal and stockpile food and supplies while vast numbers of people starve. Morning for the Osone Family ends on a positive note, looking towards a future in which the repressive power of the military has been broken and a freer, more democratic society becomes possible.

The strengths of the five films in Keisuke Kinoshita and World War II lie in this sensitive director’s careful attention to character (performances are uniformly excellent), providing a view of Japanese civilians as people much like their counterparts on the other side of the conflict, while through their propaganda elements throwing retrospective light on the forces which shaped these people into largely compliant adherents to the militarized views of their society. Much of the bitterness evident in Morning for the Osone Family stems from the sense of betrayal which followed defeat and a dawning realization that this society had been built on lies and deceptions. It was the effects of that realization which eventually gave rise to the anarchic films of the new era, with vicious amoral gangsters taking over from the armies of samurai who had clung to a rigid and death-obsessed code.

The disks

As is usual with Eclipse releases, the five films of the Kinoshita set exhibit little if any efforts at restoration. The prints are all rather battered, with scratches, missing frames, image instability and soundtracks which are thin and hissy. But that said, for the most part the images are strong, with good contrast and detail. It’s remarkable that these films have survived in a form this watchable.

Each film is on its own disk in a slim case, the only supplements being a brief essay on each by Michael Koresky which situates the films within the context of both the time of their production and Kinoshita’s subsequent career.

Comments