Miyazaki’s swan song: The Wind Rises

I’ve been more than an admirer of the films of Hayao Miyazaki ever since a friend introduced me to his work via a VHS copy of My Neighbour Totoro in the mid-’90s. Since then I’ve seen all eleven of his features, plus the TV series Future Boy Conan and Sherlock Hound. In fact, I originally saw three of his films – Nausicaa In the Valley of the Wind, Castle In the Sky, Porco Rosso – on DVDs without subtitles, which I got from eBay; it didn’t matter that I couldn’t understand the dialogue, the visuals were enough and I watched them repeatedly before the films were eventually brought out on English-friendly disks by Disney.

I’ve made a point since Princess Mononoke in 1999 to see each new feature in the theatre, despite the often dissatisfying American voices dubbed onto the films by Disney, because the richness and nuances of his art work deserve to be seen on a big screen … but I always feel that I haven’t really seen the film until I watch it with the original Japanese soundtrack on disk (I still shudder at the destructive force of Billy Bob Thornton as the sinister monk in Mononoke). This is why I don’t always form a firm opinion of Miyazaki’s films on first viewing.

Which brings me to my vague sense of uneasiness about his swansong, The Wind Rises, which I saw last week. When an artist announces that a new work will be his last, it creates a mixture of expectations in the viewer. We need the work to somehow serve as a culmination and summary of all that has gone before, the final global statement of all that the artist believes and has striven to express over decades of work. That’s a heavy load to bear and the expectation is ultimately unfair to the artist.

Yet I carried that expectation into the theatre and while from moment to moment I responded to The Wind Rises as an expression of themes and ideas familiar from the director’s entire body of work, I kept feeling that something crucial was lacking. Despite the film’s visual beauty and the genuinely moving love story at its heart, I left the theatre feeling troubled. Like so much of Miyazaki’s work, this new film expresses his passion for flight and his disappointment with the human weakness which leads us towards violence and war. In some ways, it’s a larger-scale reiteration of the hero’s rejection of human society in Porco Rosso … at least those elements linger at the edges of The Wind Rises, but in the end they remain unaddressed.

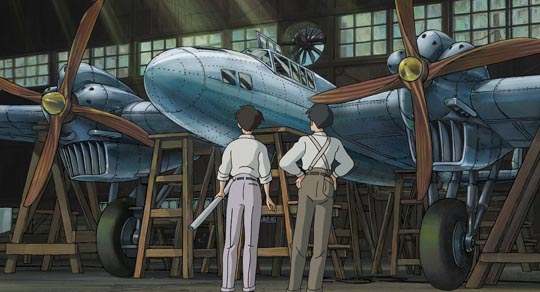

Based on the life of Jiro Horikoshi, the engineer who designed one of the most successful fighters of World War Two, the Mitsubishi Zero, Miyazaki’s film concentrates on the passion of Jiro, held since childhood, to create the perfect flying machine. This dream which shapes and directs every aspect of his life, leads to dream visions which repeatedly turn dark; his reveries slip from a soaring sense of freedom to terrifying intimations of war and destruction. But Jiro sticks to his dream. He gets work at Mitsubishi, a company working on various military contracts in the ’30s, and gradually develops the ideas and techniques necessary to produce the faster, more powerful aircraft of his dreams.

In those dreams, he also establishes a link with the Italian engineer Caproni, who also finds his revolutionary ideas co-opted by the military, transforming his dream of passenger planes into bigger and better bombers. Although Jiro feels some discomfort at the military nature of his work, he pushes this aside because this is the only way he will ever be able to accomplish his dream. There are hints throughout of the increasing militarization of the society around him, but he largely ignores them, dividing his life between his work and his love for Nahoko, a girl who is slowly dying of tuberculosis.

The underlying vision of The Wind Rises is that life is ephemeral and uncertain, but the imagination has a lasting power which goes beyond our physical limitations. This is something which can be seen in much of Miyazaki’s work. But in this instance he has chosen specifically to express the idea through the story of this particular character … and so when, after the war, surveying the shattered physical remnants of his dream, Jiro is reassured by a vision of Caproni that all that really mattered was his dream and that Jiro had realized it magnificently the implications seem completely at odds with everything Miyazaki has said in his previous films.

Given the richness of Miyazaki’s previous work and its concern with the place of human beings in the natural world and trying to find a balance which causes as little damage as possible, this seems like an odd, even dangerous, position to be taking in his final film. The Wind Rises appears to dismiss all the horrors of the war, all the death and destruction, as less important than this one man’s ambition and apart from one small moment at the end, Jiro is never required to confront the material consequences which followed inevitably (given the flawed nature of society) from his dream.

Perhaps I missed something, perhaps the English translation failed to capture nuances of the original Japanese – I’ll watch it again when it becomes available on disk with the original soundtrack – but this first viewing left me with the feeling that Miyazaki himself was so enamoured of the dream of flight (so richly expressed in many of his earlier films) that he failed to examine fully the real consequences of Jiro’s invention.

But despite these thematic problems, The Wind Rises is ravishingly beautiful to see, with all those years of mastery resulting in moments of spectacular grandeur (the devastating 1923 earthquake which destroyed much of Tokyo) and intimate moments of deeply felt emotion (the scenes between Jiro and Nahoko at a country hotel as their love flowers).

Most of the voice work by the American cast is serviceable if not particularly memorable, the single big exception being the unexpected casting of Werner Herzog as Castorp, a German also staying at the hotel who appears apparently only to serve a warning to Jiro that he’s in danger from the military state. Castorp is weakly integrated into the narrative, but Herzog gives him more personality than many of the more central characters.

Miyazaki has been one of the greatest directors of animation for more than three decades and although he has announced his retirement before, it seems likely that The Wind Rises really will be his last feature (he’s now 73). It feels a little churlish (and ungrateful) to feel even a slight sense of disappointment about the film, but that doesn’t diminish my love and respect for all the films which have preceded it; I watch them repeatedly both to revisit the rich emotions they evoke and to discover details and nuances missed on all those previous viewings. Like all the best of art, Miyazaki’s films offer inexhaustible ranges of experience.

Comments