Recent Documentary Viewing, Part 1: Paradise Lost Trilogy (1996-2011)

I’ve recently been catching up on some documentaries by favourite filmmakers which have been waiting on the shelf for a while, beginning with a trilogy about a horrific crime and an apparent miscarriage of justice.

With the release of part three of Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky’s Paradise Lost Trilogy, I decided to refresh my memory by watching the first two films again before getting to Purgatory. Like many people, I found Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills (1996) a powerful experience. The story of a particularly brutal triple murder of three 8-year-old boys (Steve Branch, Michael Moore and Christopher Byers) in West Memphis, a small Arkansas town, in 1993 and the subsequent arrest and trial of three teenagers, it provoked feelings of horror and outrage, both for the crime itself and for the handling of the investigation.

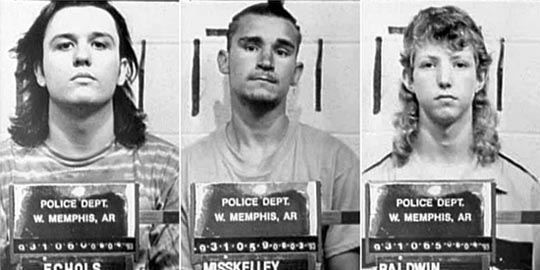

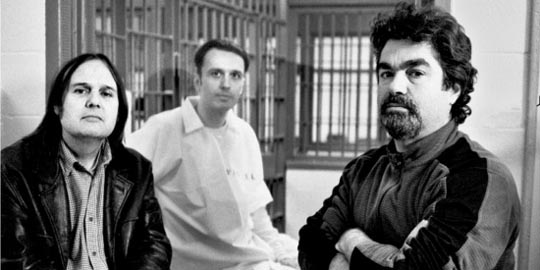

Initially going to West Memphis soon after the murders were committed, Berlinger and Sinofsky ended up filming for a year as the case unfolded, eventually becoming convinced of the three teens’ innocence. With no physical evidence to connect Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley Jr to the crime scene or the victims, the entire case hinged on a dubious confession extracted from Misskelley, a boy with low IQ who was held and questioned for some 12 hours before the police started to record the “interview”, by which time he was agreeing with whatever they told him had happened. That “confession” named Echols and Baldwin as the primary killers, something which suited the police and the community at large because Echols was a perfect “other”, a brooding teen who dressed in black, listened to heavy metal and read books about witchcraft, while Baldwin was his closest friend.

The prosecution presented a hysterical case (in two separate trials, the first for Misskelley, the second jointly for Echols and Baldwin) built around the proposition that the murders had actually been ritual killings committed as part of some satanic mass. The heightened emotions in the community were driven by the wave of (now known to be largely bogus) cases of satanic cults which erupted throughout the ’80s. Echols, seen as the prime mover in the case, conformed to everyone’s idea of a “typical” satanist … and all three boys were convicted, with Echols himself being sentenced to death.

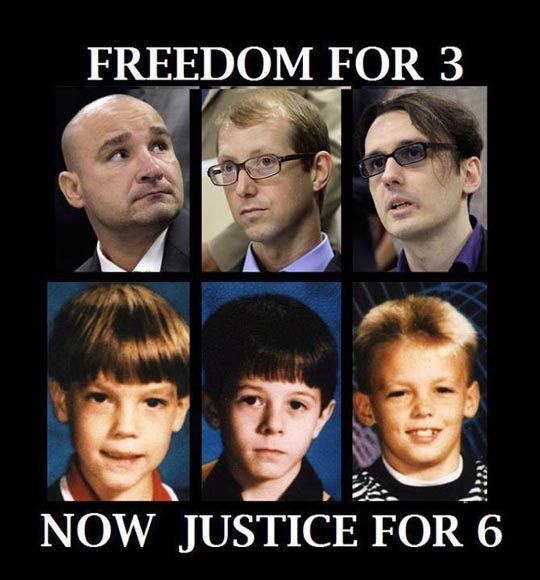

Part 2, Revelations (2000), picks up a few years after the convictions as questions about the case inflamed a movement to free what had become known as the West Memphis Three. New lawyers and appeals pushed for a rehearing of the case, a process which was to continue for many more years – in one of the most dubious instances of questionable justice, every appeal was heard by the original trial judge, who time and again ruled against the three.

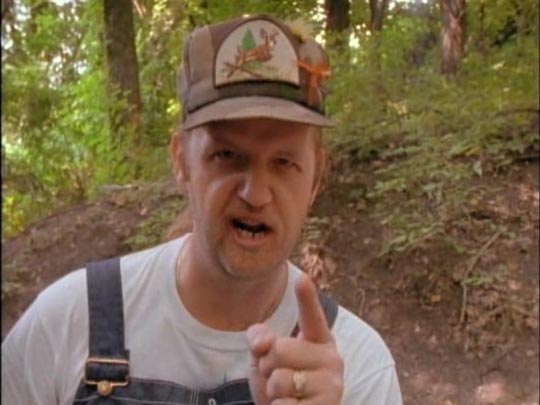

The most disturbing aspect of the second film, though, was the presence of John Mark Byers, stepfather of one of the victims, a man who allowed himself to be placed front and centre by the filmmakers as he ranted and performed for the camera, coming to appear not only as a deranged religious zealot but also as a disturbingly plausible candidate for perpetrator of the crimes himself. The uses he’s put to by Berlinger and Sinofsky are increasingly troubling as his mental instability becomes clearer and the presence of the camera spurs him to increasingly more extreme behaviour; he literally performs for the camera and the filmmakers make full use of his willingness, leaving the viewer finally convinced that he may well have been the killer.

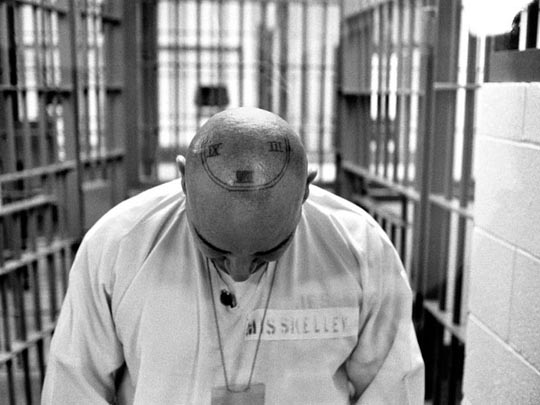

Revelations is a gripping film, but it also seems overly manipulative. It’s only with the final film, Purgatory (2011), released almost 14 years later, that it really comes into focus. This third part is surprising for the amount of new material from the original period of the project – interviews from the time which were not used in the first two films – as well as the changes which had occurred in the intervening decade as the three boys grew in prison, Echols and Baldwin becoming thoughtful, articulate men, while Misskelley is revealed as perhaps the saddest case, a mentally weak boy who was pushed into helping to destroy the lives of the other two and now grapples with the implications of what he was forced to do.

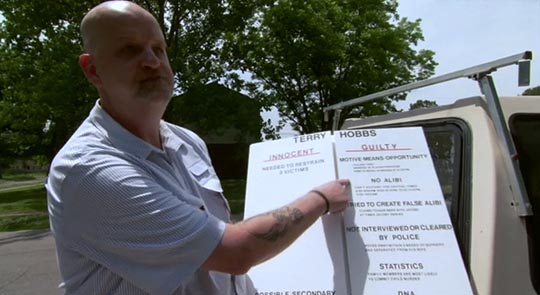

But the most interesting aspect of Purgatory is how the movement to reopen the case has developed since part 2. A loosely organized coalition of concerned people from all over the States regularly show up to attend every new hearing; an alliance of highly qualified and respected experts reevaluate the evidence in the case and make it increasingly clear that everything was misinterpreted through that prejudicial filter of satanic hysteria. And, most importantly, at least two members of the victims’ families are now also on the side of the convicted boys – including, most remarkably, John Mark Byers, who has come through his own traumatic experiences (the death of his wife in suspicious circumstances, various legal problems, mental health issues) to argue for the release of the three.

It’s through Byers’ interactions with Berlinger and Sinofsky here that we can see just what was going on in Revelations; that that film was demonstrating how easy it is to construct a seemingly plausible case against someone who doesn’t fit in, and by extension implying just how tenuous and circumstantial the case against the three was. Revelations demonstrates, by playing on even a liberal-minded audience’s innate, perhaps unacknowledged, prejudices just how easy it is to condemn someone whose beliefs and behaviour don’t conform with our own.

Taken together, the three Paradise Lost documentaries become an epic contemplation of just how fragile the concept of proof and certainty can be, a disturbing idea which is really driven home by the (to date) final outcome of the case. Facing the almost inevitable reopening of the case, with a consequent new trial which itself could drag on for years, the prosecutors get Echols, Baldwin and Misskelley to offer an Alford plea, a bizarre bit of legal mumbo-jumbo which allows the three to assert their innocence while also pleading guilty to the crime they didn’t commit. This allows the state to declare that they have finally got an admission of guilt, while the accused simultaneously get it on record that they don’t actually admit any guilt. This sleight of hand somehow justifies the state (which continues to assert their guilt) to release them from prison (sentenced to time served plus ten year suspended sentences). It’s the final obscene detail of a horrific case, the upshot of which is that the real killer is no doubt still at large, but the state feels no obligation to do anything about it.

Because of the impact of the original film, Berlinger and Sinofsky and their work became inextricably connected to the on-going legal process. The presence of the filmmakers and their cameras at the original trial, and their relationship with the defendants and their counsel, eventually became a factor in the appeals being filed as the new legal representatives of Echols and Baldwin asserted that the documentary-in-the-making had had a prejudicial effect on the trial. As a result, Berlinger and Sinofsky were barred from shooting inside the courtroom for subsequent proceedings. It’s inevitable, because of their close connection, that the filmmakers become increasingly self-referential in the later films – a fact which some have seen as shamelessly self-promoting, although it seems objectively unavoidable given that much of the attention the case received at the time and subsequently was, in fact, due to the presence of the documentarians. The case might well have remained a local affair without the film, a fact so obvious that to try to avoid mentioning themselves and Paradise Lost in the sequels would have become at least puzzling, if not potentially a distortion of the story.

*

Docurama’s four-disk DVD set has a lot of additional material – deleted scenes and interviews – but the quality of the first two disks is appalling, to the point of being constantly irritating to watch. Paradise Lost and Revelations seem to have been made from original television masters, with a smeary, unstable image. Purgatory looks pristine by comparison, even the material shot back in 1993-94, obviously newly transferred in HD from the original film footage. A pity the company didn’t make an effort to create new, cleaner transfers of the first two films.

Comments