Jean Rouch, Edgar Morin, cinema verite and the problem of “actuality”

The late ’50s saw the biggest technology-based shift in movies since the coming of sound (the next big shift would be the arrival of digital technology several decades later). New highly portable equipment not only altered the way movies were made, it also altered creative choices and even content. New lightweight cameras and sync sound gear facilitated the New Wave, which along with this equipment adopted neo-realist dramatic techniques to transform (and undermine) classic narrative cinema. And just as importantly, the new technology transformed the very idea of documentary.

In North America this saw the arrival of the “direct cinema” movement, which viewed itself as getting as close to unmediated experience as possible, facilitating the uninflected depiction of the real (a myth, of course, as like all film even the works of Pennebaker, Leacock, and the Maysles brothers in the U.S. and people like Wolf Koenig, Roman Kroiter and others at the National Film Board in Canada were constructed and shaped by the filmmakers’ intentions). In France, there was cinema verite – literally, the filming of truth. Unlike direct cinema, this movement admitted the presence of the filmmaker in the process … and Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin’s Chronicle of a Summer (1961) might stand as the quintessential example because to a large degree its very subject is the directors’ attempt to access social and political reality by entering into an active dialogue with their subjects.

Rouch was an ethnographic filmmaker whose work largely dealt with the African experience of colonialism, while Morin was a sociologist. It was Morin who suggested to Rouch that he turn his ethnographer’s eye to contemporary life in France and together in the summer of 1960, at the height of the Algerian war of independence, the pair set out to find out about how people saw and lived their lives, taking as their starting point the question: “Are you happy?”

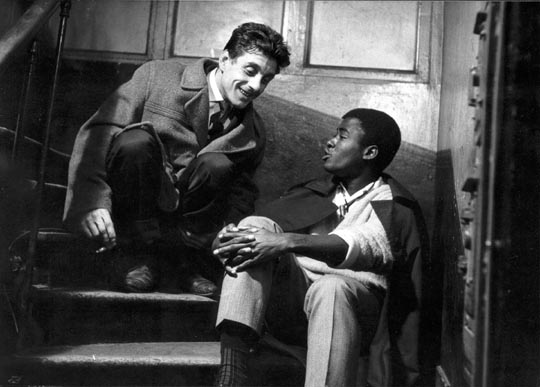

Although shot much later in the process, the film begins with two women going out into the Paris streets with a tape recorder to ask passersby that question. They get mostly brief answers from those who do stop to speak to them – many people quickly walk past as if irritated or embarrassed. The film then moves into interiors, where Rouch and Morin gather small groups to eat large meals and talk about their lives. Not surprisingly, these sequences come across as gatherings of French intellectuals speaking airily about abstract notions of life and happiness. But then we meet a factory worker, and he is introduced to an African student and the two of them – one exploited labour, the other coming from a colonial background – seem to find a mutual connection in their conditions of exploitation.

One of the women we meet in that opening sequence, Marceline Loridan, suddenly reveals something of her past in a startling sequence in which she walks through a nearly deserted Place de la Concorde: in a hand-held tracking shot through the famous open space she tells us of being rounded up with her family as a girl and shipped off to a Nazi death camp where she alone survived. In another emotional scene, this time in a small apartment, the Italian exile Marilu Parolini (who worked for Cahiers du Cinema and later married the formidable Jacques Rivette) exposes her insecurity, her sense of precarious identity in this foreign city.

The meal-time conversations become more revealing as people speak increasingly openly about the current political situation, about their moral positions in relation to the Algerian war and the men’s need to choose either resistance or participation in France’s military actions; there is discussion of what’s happening in Africa (particularly the Congo) as European colonialism approaches its bloody end. What began as a “scientific” investigation is escaping the directors’ control, the messy ambiguities and complications of actual lived existence refusing to give up clear answers.

Towards the end, as part of the process (and the film is most clearly about process), Morin and Rouch gather many of the participants in a screening room and show them scenes from the work in progress, hoping that the action of participating in the film will have revealed to them all a commonality of experience across class, gender, national and racial lines – hoping that the investigation itself will have broken down barriers and in some sense effected political change on a personal level. The filmmakers are surprised, even shocked, to discover the opposite as members of the cast/audience begin to dissect each other’s on-screen personae, with some accusing others of faking their emotions, their moral and political positions, for the camera.

Is this simply an example of the “observer effect”, the act of watching changing what is being watched? Or, more profoundly, does the process of making the film quite inadvertently reveal the performative nature of human behaviour, that each of us is the central actor in our own life? But isn’t that notion of performance itself a result of the invention of the camera? Photography produced a kind of self-awareness which had not existed in the previous tens of thousands of years of human evolution; the camera enabled us to step outside ourselves and see ourselves as an observer would. This awareness of being seen, of being watched, perhaps itself transformed our behaviour into a kind of performance. In which case, of course, it’s literally impossible to capture anybody’s “natural” behaviour on film.

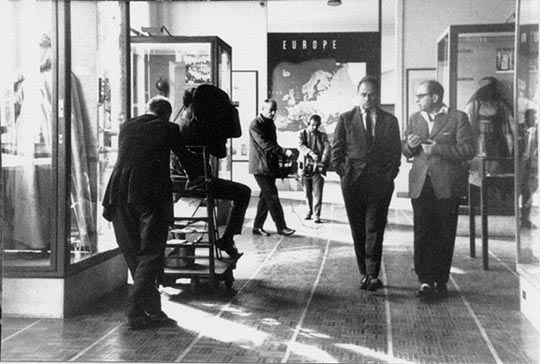

Chronicle of a Summer ends with an intense discussion between Rouch and Morin, pacing among the exhibits of the Musee de l’homme, about what conclusions they can draw from the apparent failure of their experiment, only to come finally to realize that they themselves no longer stand outside the process as filmmakers, but are as deeply implicated in the performance as any of their subjects … that in fact they, along with their subjects, have been caught on film in the midst of the on-going flow of life in all its messy complications.

The raggedness of the film, the jarring shifts from the intellectual dinner-table discussions to the vibrant street scenes, is itself a reflection of the impossibility of pinning down that flow with scientific precision. There are two styles in conflict in the film, and yet paradoxically supporting and informing each other: the staged discussions and the mobile pursuit – the latter a result of Rouch’s realization that the film was bogging down in intellectual sterility. This was when he imported Michel Brault from Canada, the National Film Board filmmaker arriving with his lightweight camera and dynamic hand-held techniques to open up the film to new observational possibilities. (It was Brault, later the director of the remarkable ethnographic documentary Pour la suite du monde [1963] and the scathing docu-drama Les ordres [1974] about the imposition of the War Measures Act during the FLQ crisis in 1970, who shot Marceline’s single-take walking monologue through Place de la Concorde.)

Chronicle of a Summer, as a key exemplar of cinema verite, engages with the life it observes and generates endless questions rather than providing clear-cut answers.

*

The “actuality” of Wonderful London (1924)

A recent DVD from the BFI offers an interesting comparison with Rouch and Morin’s engagement with and participation in the material of their documentary. The very earliest movies were “actualities”, single shots depicting a moment or event occurring in the world – the workers leaving the Lumiere factory, the train arriving at la Ciotat station. Very quickly, filmmakers realized that they could stage events for the camera, already compromising the idea of unfiltered reality. Documentary since its beginnings has had to deal with (often by ignoring or disguising) the fact that the camera’s presence by its very nature alters what is being recorded to some degree. And yet, looking at images made a hundred or more years ago, even knowing this, we are enthralled by glimpses of a world and lives which have vanished. There’s something almost mystical about street scenes from the early days of cinema, the tantalizing idea that we can almost, almost reach out and touch this ghostly world …

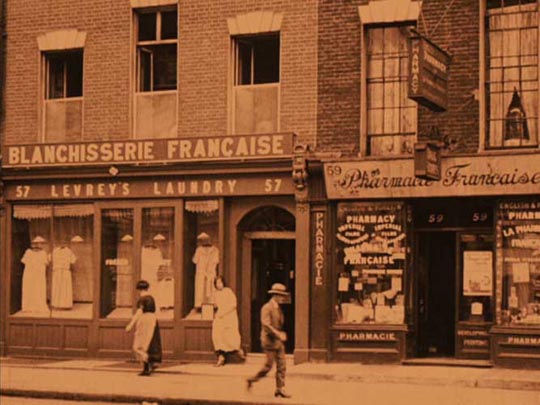

Wonderful London, a collection of short sketches and travelogues from 1924 made by Harry B. Parkinson and Frank Miller, supplies those kinds of images and evokes those enticing feelings; while often their focus is on edifices, streets and architecture, our modern eyes are more likely to be drawn to the people bustling through their scenes, the movement of bodies, the fleeting expressions glimpsed on faces which occasionally turn to look at the camera and seem to glance back at us. Made just six years after the end of the First World War, these sketches of the vast cosmopolitan city reveal layers of time, ancient buildings beside modern, horse-drawn vehicles among motorized traffic – the filmmakers repeatedly call attention to these traces of history (one film deals with the legacy of Dickens; references are made to executions at Tyburn, to the lives and deaths of kings).

But Parkinson and Miller complicate the seeming simplicity of “actuality” by alternating their wondrously mundane images of the city’s streets and their inhabitants with title cards which add comments often at odds with what we’re seeing. Like promoters of tourism, they eagerly tout the wonders of the metropolis, but there are hints throughout that something is being lost with the passage of time (and glimpses we get of the Crystal Palace just a few years before its destruction and the vast White City stadium, already decaying just 20 years after its construction, serve to underline the point). In the most striking of the twelve films on the disk, Cosmopolitan London, they tout the foreign wonders in their midst, the influx of European and colonial immigrants bringing with them fragments of their own cultures, and yet can’t disguise a degree of unease, even distaste, with pointed comments about the strange habits of Lascars, the alienness of the East End’s Jews, and the undoubted criminality of the Asians who inhabit Limehouse, even though the images themselves don’t support these judgements. As if in relief, the filmmakers escape back to the safety of Horse Guards Parade and the reassuring sight of proud soldiers passing in review to remind us “that there is still something British in Wonderful London.”

While in Rouch and Morin’s film we witness an attempt to explore and discover something about life as it is lived, in Wonderful London we see an attempt to impose meaning on something which pre-exists the films, to fix something like a specimen pinned to a board, rather than get caught up in its chaotic flow. And yet in both cases, the filmmakers have turned their cameras on a world which refuses to be contained by their intentions. It’s just that in the case of Wonderful London you wish Parkinson and Miller would shut up and let us look, while in Chronicle of a Summer Rouch and Morin’s commentary on their process deepens out interest by raising questions about what it is we are doing when we do look at the world.

*

Criterion’s Blu-ray edition of Chronicle of a Summer includes an illuminating feature-length retrospective documentary containing a lot of fascinating outtakes which reveal more about the process than we see in the film itself; and also interviews with many of the participants, including Edgar Morin, who recall the experience of making the film. The lengthy essay by Sam di Iorio in the accompanying booklet is essential reading for insights into just how radical the project was for its time, and indeed remains today.

The BFI’s region-free PAL DVD of Wonderful London contains six of the 10-12 minute films restored with original colour-tinting, and an additional six unrestored as extras. Not surprisingly, all of them – restored and unrestored – exhibit a lot of wear, with surface scratches, missing frames, occasional image instability. But the clarity and detail of the images is often remarkable, making you wish that shots were held longer so you could spend more time taking in the sights.

Comments

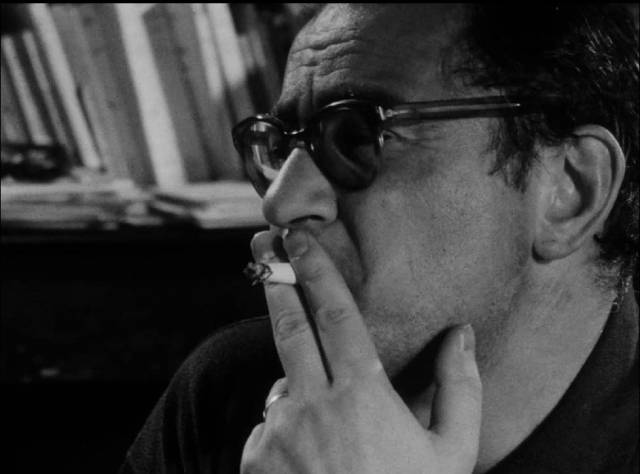

The photo labelled ‘Edgar Morin’ I do not think is actually Edgar Morin (he has too much hair for a start lol)

Yes, looks like I misidentified the original image – I’ve replaced it with one which is definitely Edgar Morin.