DVD Review: Medium Cool (1969)

It’s interesting that Criterion has released Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool (1969) so soon after Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin’s Chronicle of a Summer (1962). The two films, separated by an ocean, by different cultures and by almost a decade, represent two distinct approaches to the same essential problem: is it possible for film to capture reality? To what degree is film always, inevitably a fiction?

While Rouch and Morin set out to turn an ethnographer’s eye on contemporary social and political life in Paris in 1961, Wexler initially set out to make a drama in his home town of Chicago. A respected cinematographer with extensive documentary experience, he had been offered a book called The Concrete Wilderness by Jack Couffer to adapt; this was about a boy who establishes connections with animals living in the city. While traces of the book linger in the finished film, Wexler found himself drawn to the on-going political situation of 1968 and Medium Cool became something almost unique in American cinema.

With the country shaken by social unrest rooted in both the struggle for civil rights and opposition to the Vietnam war, Hollywood was uncertain how to deal with the contemporary situation (there were a rash of “counter-culture” movies in the late ’60s and early ’70s which tend to look embarrassingly naive in retrospect – in 1970 alone, the year after Medium Cool was released, there were Stuart Hagmann’s The Strawberry Statement, Richard Rush’s Getting Straight and Stanley Kramer’s R.P.M.), so it’s not surprising that the most perceptive movie from 1968, a year of riots, assassinations and political upheaval, should have come from outside the system, the work of a filmmaker with a great deal of documentary experience and a history of political commitment.

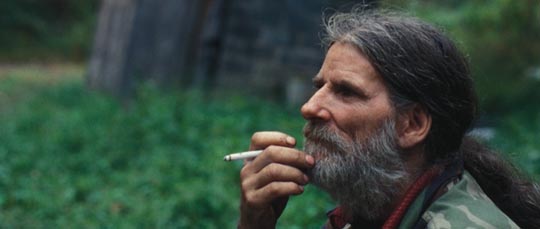

Wexler transformed the source material into a loose story about television cameraman John Cassellis (Robert Forster in his first lead role), whose passion is making images, recording the world around him, but who remains detached and unreflective – he doesn’t think about what he’s seeing and recording; he believes that he’s simply capturing truth on film. In Chicago leading up to the Democratic national convention, events gradually crack his belief in his own neutrality. This process is accelerated when he meets Eileen (Verna Bloom), a woman displaced from the coal-mining country of Appalachia, and her young son Harold (Harold Blakenship), whose passion for homing pigeons is all that remains of the novel.

The small, tentative story of this trio’s developing relationships is played out in a city which is becoming increasingly militarized as Mayor Daley prepares to confront anti-war protests with brutal force. The strength of Wexler’s film lies in the way he embeds the personal story in the documentary reality – the city isn’t merely backdrop to the potential romance (as it would almost inevitably be in a mainstream Hollywood movie); what Wexler captures with dramatic and emotional force are the ways in which the social tensions and violence of that summer affect and shape private experience. Perhaps more than any other movie, Medium Cool proves the dictum “the personal is political”, or perhaps that should be “the political is personal”.

While the viewer is engaged by the characters, particularly Eileen and Harold – Bloom and Blankenship are heartbreakingly believable – what finally gives Medium Cool its dramatic power is the documentary material which surrounds them. With its focus on a TV cameraman, the film has access to a remarkable range of experience. Early on, we see the training of a National Guard unit in riot control techniques, with some guardsmen acting as demonstrators while others contain them; this comes across as pure theatre, a game, emphasizing what became the core insight of Rouch and Morin’s film: that all social behaviour is performance.

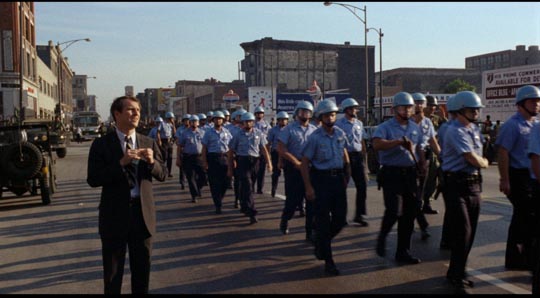

By the time we get to the demonstrations, and finally the riots outside the convention, it has become clear that what is really being expressed by the protesters (a political disagreement with the way their democratic society is being run) has been lost; the authorities under Mayor Daley have redefined the situation, assigning the role of enemies of the state to the protesters, thus justifying official violence against American citizens (subsequent enquiries labelled what happened as “a police riot”). The images of armoured police, the presence of the National Guard in full military gear, tanks and armoured troop carriers on the streets, plumes of tear gas and blood-streaked faces, still have a chilling power (reminiscent of the images of the military coup in Chile in Costa-Gavras’ Missing [1982]).

Remarkably, Wexler and Bloom wander through the chaos (her character is searching for her missing son) and he captures close-up images of the violence, much of which was not observed directly by the media at the time because, after police warnings, the real network news crews pulled out as the police launched their assault. And so, this mix of fact and fiction becomes one of the most faithful records of what actually happened.

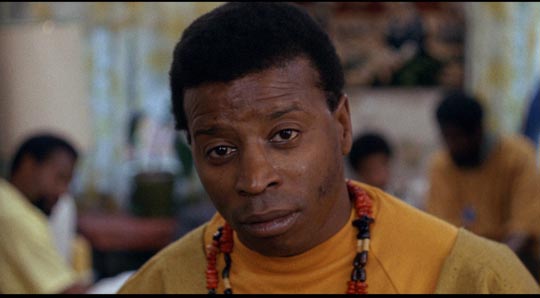

But before that climactic sequence, Wexler has explored other aspects of the city and its ready-to-boil political conflicts. Following up on a “human interest” story about a black cab driver who found a bag containing $10,000 on his back seat and turned it in, Cassellis and his soundman Gus (Peter Bonerz) go into an area where whites tend not to go without protection. There’s a brief moment on a street corner with a black teenager haranguing Gus for daring to come down here and buy cigarettes at the corner store – this wasn’t staged, but was an actual moment captured by Wexler with a hidden camera.

When the pair get to the cab driver’s apartment, they encounter a group of very politically aware people (not actors) who challenge them about this act of media tourism and confront them with passionate and nuanced political arguments rooted in centuries of oppression. This scene reminded me of parts of Lionel Rogosin’s “docu-drama” about apartheid, Come Back, Africa (1959), in which he also gathered together a group of artists and writers to talk about their experience of racism and disenfranchisement.

But Medium Cool isn’t a simple essay on white vs black, establishment vs counterculture. By creating the characters of Eileen and Harold, and shooting in the white slums largely populated by displaced workers from Appalachia, the film underlines the class divisions which define American society as much as the racial divisions. And the final assault by the police reveals the power of the ruling class to maintain a status quo which imposes misery on a large percentage of the population.

(*Possible spoiler*) The framing device used by Wexler has been much discussed and, for me at least, seems like the most self-conscious aspect of the film. The opening scene has Cassellis and Gus shooting footage of an injured woman trapped in a car which has crashed on the freeway; they move around the scene quickly and efficiently and only as they walk back to their own car does it occur to them to call for an ambulance. The sequence seems rather forced, over-determined, bluntly making an editorial point about the callousness of Cassellis and by extension all news media.

The ending seems even more self- consciously calculated and dramatically arbitrary. Having reconnected during the riot, Eileen and Cassellis get in his car and start driving – it’s not clear where they’re rushing off to, but as they drive along a tree-shaded street, we hear a report over the radio announcing a car crash in which Eileen has been killed and Cassellis seriously injured … at which point the car crashes (in contrast to the clarity of the film’s documentary footage, this is entirely constructed through montage, piecing together fragmentary images). As the car rests smoking by the road, some rubber-neckers drive by and snap photographs, hammering the point that Cassellis’ own reporter’s detachment has infected the public which views the news.

Then the shot pulls slowly back, the crashed car in the distance, and pans to find Wexler up on a scaffolding, shooting the scene and, in the film’s final moment, turning his camera to point the lens directly out of the screen at the audience. The point that we’re all implicated, that what we perceive as reality is now a media construct which we have internalized, has already been made through the intricate construction of the film, so this ending, like the opening, seems over-determined, another editorial imposition, as if Wexler felt the need to make absolutely certain that the audience understood what he was saying. (*End of spoiler*)

But apart from these two self-conscious moments, Wexler uses the techniques of cinema verite (film truth) to create a personal drama which is also one of the most incisive political statements in the history of American film. And even more than 40 years after its original release, it retains the power to shock and stimulate consideration of the way this society is run.

This last point is underlined by one of the many supplements on the Criterion release, Medium Cool Revisted, a half-hour short shot by Wexler during the 2012 NATO summit in Chicago where we see again the same power dynamics, with the streets shut down by a heavy military presence as the Occupy movement protests against the multi-national meeting of men in suits to decide high level policies that citizens have no power to affect.

*

The Disk

Criterion presents a beautiful new 4K restored transfer which gives the feature a vibrant film look. The mono audio taken from an original 35mm source is clear and detailed.

The Extras

In addition to the short documentary mentioned above, the 2-disk set is packed with an exhausting array of supplements. Inevitably there is a certain amount of repetition, but the range of information provides a richly detailed account of the film’s production, Wexler’s intentions and methods, and the important position Medium Cool holds in American film.

There are two separate commentary tracks: the first, recorded in 2001, with Wexler, editor Paul Golding, and actress Marianna Hill (who plays the small role of Cassellis’ girlfriend early in the film); the second with historian Paul Cronin. The group track is loose and engaging, while the second is pretty dry, though packed with interesting information which ranges beyond the film itself to the politics of the time and the connections between Medium Cool and the documentary and cinema verite movements which informed its making.

“Look Out, Haskell, It’s Real!” is a one-hour version of a massive documentary project Cronin has been working on for years to document the production (a six-hour version can be viewed on-line in here). This duplicates a lot of what we hear in the commentaries, but additionally talks to other people involved, like the writer and historian Studs Terkel who was crucial in getting the crew access to more “dangerous” parts of Chicago and to people who had no reason to trust the media.

There are also excerpts from another Paul Cronin documentary, Sooner or Later, about Harold Blankenship, the illiterate boy who gave such a remarkable performance as Harold and who subsequently returned to Appalachia and a life of poverty. (The full length version can be viewed on-line here.)

And finally, there’s a lengthy new interview with Wexler about the film and his work, plus a booklet with an essay by critic Thomas Beard.

The Criterion edition of Medium Cool is one of their most impressive packages, giving this powerful and important film its full due as a landmark of American cinema.

Comments