DVD Review: Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend (1967)

Jean-Luc Godard wasn’t the first of the Cahiers du Cinema critics to start making movies, but his debut feature, A bout de souffle (Breathless, 1960), was the one which most clearly announced the arrival of the nouvelle vague. Where Francois Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Louis Malle and others were stretching the possibilities of conventional narrative form, Godard seemed impatient to shatter those conventions. His knowledge of film history, style and genre was formidable, and in his first decade as a director he attacked cinema as if determined to smash it open and find new ways of constructing meaning with the fragments.

From 1960 to 1967, Godard made more than a dozen features, plus several shorts and segments of collaborative films. He made domestic comedies, war films, crime movies … but always using distancing techniques which questioned the form he was working with, to examine the underlying values and to encourage his audience to explore the ideology of an increasingly commercialized society. By 1967, he had pretty much exhausted the possibilities of this approach and his interest in film became subordinate to his radical politics. He spent most of the ’70s putting out Maoist tracts. But the transition between these phases was marked by the production of what may well be his most aggressively confrontational film.

Weekend (1967), made with his largest budget yet, is an absurdist apocalyptic depiction of the complete disintegration of contemporary French (and by extension, Western) society. It’s said that Godard didn’t like his financial backers and set out to deliver something guaranteed to offend them. He made no concessions to the audience, insistently refusing to provide characters with whom a viewer could make any emotional connection.

The opening fragmentary scenes establish a suggestion of a narrative that quickly evaporates. Husband and wife Roland (Jean Yanne) and Corinne Durand (Mireille Darc) are each telling a lover about plans to kill the other once they’ve received an inheritance from Corinne’s ailing father. These scenes are interrupted by a violent incident in a parking lot below the balcony, a moment of driver rage which foreshadows the automobile mayhem to come. Then we get a lengthy scene in which Corinne, dressed only in underwear, relates to an impassive Roland a lengthy three-way sexual encounter (drawn from Georges Bataille’s Story of the Eye [1928]), which may or may not have actually happened.

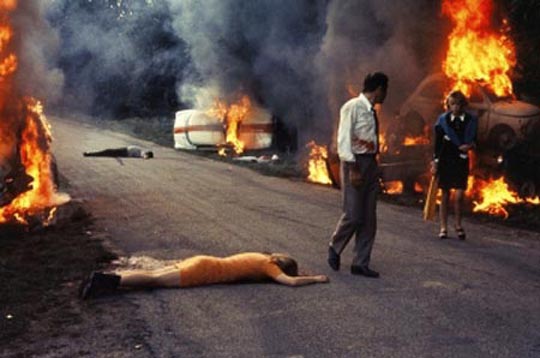

Then the couple hit the road for a weekend drive to her parents’ place. From here the film fragments into a series of increasingly violent incidents, starting with the famous eight-minute traffic jam on a country road. In just four shots, Godard displays his visual virtuosity with a three-hundred meter tracking movement as Roland cuts in and out of the blocked traffic. This is like a nightmare version of a Jacques Tati sequence, during which we glimpse odd pieces of discordant human behaviour, while in the background we see more and more wrecked vehicles pushed off to the side of the road. But for all the detail, Godard makes no attempt at any kind of naturalism; the lane away from the camera is empty and Roland is the only driver making any effort to move forward, while others merely blow their horns endlessly, toss balls, play chess, and seem to accept their frustrated situation. When the sequence finally ends, we see a multi-car crash with bloody bodies scattered in the road, the inevitable end point, it seems, of the stasis in which everyone is trapped.

The entire journey is marked by crashes and deaths, but Roland and Corinne remain unaffected. When their car crashes in flames, we hear Corinne’s pained scream for the loss of her Hermes bag, more emotionally devastating to her than all the carnage and death around them. These are one-dimensional characters motivated only by self-interest and greed. Reduced to continuing on foot, they encounter a series of historical and literary figures – Saint-Just, one of the bloodiest figures of the French Revolution (a brief appearance by New Wave mainstay Jean-Pierre Leaud); Emily Bronte and Tom Thumb … there’s a Mozart piano recital in a barnyard … scattered reflections of history and culture to whose meaning the bourgeois couple remain impervious.

What narrative there is in Weekend all but disappears as the journey continues; the scene at the parents’ house is just a throwaway. And eventually Roland and Corinne are captured by a band of hippie revolutionaries who live in the woods and seem to survive by preying on tourists, robbing and eating them … this final sequence, accompanied by a lengthy drum solo and a voice-over speaking lines from Lautreamont’s poetry, is like a horror reworking of the idyllic conclusion of Francois Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451, released the previous year, in which the members of a commune devote their lives to preserving the literary culture abandoned by a vacuous and bankrupt society. But for Godard there is no romance here, just violence and cannibalism.

In retrospect, it looks as if Godard had prescient knowledge of the social explosions which would occur in early 1968, shortly after the film’s release. But the sense of epic apocalypse in Weekend seems larger than a mere reflection of current social conflicts. There’s an air of deep disgust at humanity in general; the apocalypse is shown as an almost desirable washing away of a civilization which has reached bottom.

As in many of Godard’s films, the visuals are frequently interrupted by large blocks of text, ironic commentary and political slogans, and the imagery itself is harsh and ugly by conventional standards. The director had cinematographer Raoul Coutard underexpose the fastest film stock available at the time and push it in the lab, creating heavy grain and murky colours, with detail often obscured. The soundtrack is harsh and grating – endless car horns and cacophonous voices fighting with classical music. You get the distinct impression that Godard would be happy if the film drove its audience out of the theatre … in fact the final card reads “The end of cinema”. It’s said that the director told his crew at the end of production that they should look for work elsewhere because he was finished with traditional ways of making movies (although Coutard, in an interview on the disk, denies ever hearing this).

In Godard’s previous work, for all its experimentation, there was often a sense of play, and even charm; those films offered pleasures to an audience that was willing to go beyond classical conventions, they were in fact often highly entertaining. As fascinating as Weekend is, it can’t be called entertaining. The viewer may even feel that he or she is engaged in a kind of combat with the director; to accept Godard’s view as expressed here would lead to despair. And yet, much of the underlying critique of a complacent consumer society is hard to discount. But to engage with the film is to question a lot of assumptions which make life in a western capitalist society comfortable. In this respect, Weekend is a far more powerful political work than many of the didactic films that would follow it.

The disc

Criterion’s new DVD release of Weekend (also available on Blu-ray) is, given the deliberately degraded look of much of the photography, garishly colourful in an anamorphic 1.66:1 transfer; the original French mono soundtrack is as harsh and often irritating as Godard intended.

The supplements

Criterion include brief archival interviews with Yanne and Darc; a lengthy interview with cinematographer Raoul Coutard about his relationship with Godard and the making of the film; and an interview with assistant director Claude Miller which offers some fascinating insights into Godard’s working process – a combination of improvisation and detailed planning. We get a great deal of admiration for the director’s formidable skills as a filmmaker, but also a harsh portrait of him as a human being; apparently he despised Darc and spent the entire production heaping more and more abuse on her (the “Hermes” line was an ad-lib she tossed out to defuse his anger when she jumped from a real burning car sooner than he wanted).

There is also a short excerpt from French television which shows Godard directing on location, and a lengthy video essay on Godard by Kent Jones, which is too scattered to be really satisfying, although he offers some useful insights into the director’s art. The accompanying booklet has a brief essay by Gary Giddings, excerpts from a contemporary interview with Godard and comments from some of his collaborators.

Comments