Viewing notes, March-April 2015: part one

As usual, I haven’t managed to keep up here with comments on everything I’ve been watching. No doubt I should spend less time watching movies and more time writing about them!

I caught two movies in theatres a couple of weeks back, one big, expensive and guaranteed to be a commercial hit; the other small, quirky and on the whole much more interesting.

Furious 7 (James Wan, 2015)

The Fast & Furious series began quite modestly in 2001 with a movie about a cop going undercover to infiltrate a gang of illegal street racers and car thieves, then floundered a bit with a first sequel which focused on the cop while ditching the first film’s star (Vin Diesel) and a second sequel which ditched all the original characters and moved to Japan. It was with the fourth film that the series finally found its identity as a kind of Bond/Mission: Impossible hybrid in which a multi-ethnic family of extreme drivers, despite being outlaws, are recruited by various government agencies to fight crime and uber-criminals bent on world domination. From there on, the movies got bigger, more cartoonish, and more determinedly sentimental about the bonds of family.

The latest installment, Furious 7, stretches the formula to breaking point. While the epic set-pieces of number 6 pushed the series into blatant action fantasy (the ludicrously overblown battle with the tank and the climactic, interminable giant-plane-on-a-twenty-mile-long-runway chase), the appeal of the characters managed to hold it together. But the new film shows signs of laziness in a script which barely manages to hold together a string of action scenes which make less and less sense as they go on. In a quest for sheer destructive spectacle, the team manage to destroy huge swaths of Los Angeles in a showdown with a warlord who is so determined to kill Dominic Toretto (Diesel) that he flies around the streets in a helicopter gunship while using a missile-laden drone to blow up everything in sight. None of this makes any story sense and although the movie elides the issue of collateral damage, god knows how many innocent bystanders are casually slaughtered while we’re asked to worry about the team’s survival. The movie plunges out of narrative and into the mechanics of a video game.

Overshadowing all the vehicular mayhem is an awareness of the real-life car crash death of co-star Paul Walker during production, a fact which gives a queasy edge to all the scenes of our heroes walking away from impossible crashes. It was no doubt inevitable that the movie would somehow address Walker’s death (and unavoidable exit from the series), the filmmakers don’t simply embed his departure in the narrative (with the Brian O’Conner character retiring to be with his family); they build the entire ending around a maudlin farewell to Walker the actor. This inability to separate the movie fantasy from an external reality makes the excesses of the action seem even more ridiculous. An eighth movie is already in production, but it’s hard to see where the series can go from here.

*

It Follows (David Robert Mitchell, 2014)

Probably made for less than the craft services budget on Furious 7, David Robert Mitchell’s It Follows has something completely lacking from the big action movie: personality. Quirky, thematically problematic, this modest horror movie benefits from originality, a good cast and skillful direction. In many ways a deliberate throwback to ’80s teen horror, it has atmosphere which is firmly rooted in a realistic observation of character and setting. Teenager Jay (Maika Monroe) has sex with new boyfriend Hugh (Jake Weary) in his car, only to have things suddenly turn nasty when he drugs her and she wakes up tied to a chair in a derelict building, where he explains that he’s sorry but he had no choice but to pass on his curse. It seems that there’s a kind of demon which is passed on through sex; it will kill the recipient unless he or she finds someone to have sex with before it reaches them.

Jay manages to convince her sister and friends that there really is a threat (only she can see the figure, which can take on any identity as it walks inexorably towards its intended victim). Mitchell creates a palpable sense of paranoia which escalates as the friends try to figure out a way to save Jay. Mitchell plays everything straight and his cast perform with a refreshing sense of conviction. There’s no irony, no sending up of the concept. The one miscalculation is the overwrought ’80s-style synth score which is too often intrusive and works against the carefully created atmosphere. (The 22-year-old daughter of a friend told me that she and her friends found the whole film laughable, their negative response beginning with that overblown score.)

As to the implications of the film’s supernatural VD metaphor, when I left the theatre I commented to my friend Curtis that It Follows would make an excellent set text for abstinence-only sex ed classes; he responded that he thought the movie actually promoted “having more sex”. In retrospect, it rather seems to suggest that you should have lots more sex with people you don’t know while avoiding sex with people you actually like. In some ways, It Follows is reminiscent of David Cronenberg’s early “venereal horror” movies in its complicated attitude towards sexuality. Whatever Mitchell’s actual intentions, It Follows is an effective little horror which would make an excellent double feature with Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook.

On disk

Alfred Hitchcock: Rear Window (1954)/The Birds (1963)

Home viewing has been a bit eclectic. I recently revisited two of my favourite Hitchcock features on Blu-ray and they held up very well. Rear Window is almost a primer on Hitchcock’s obsessions and techniques, its setting evoking the theatre in which the audience watching the movie is sitting; photographer L.B. Jeffries (James Stewart), stuck in his apartment with a broken leg, spends his days watching his neighbours across the courtyard, piecing together a series of narratives which turn gradually darker as he comes to suspect that one of them has murdered his wife. There’s a rich sense of life in this tightly contained space, and Hitchcock revels in the ambiguous implications that Jeffries’ voyeurism has for the movie audience.

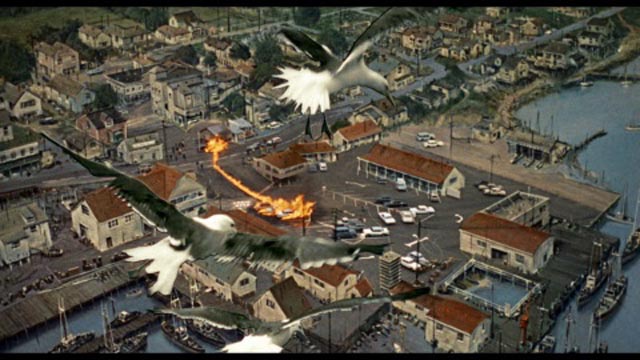

The Birds is very different, with its open-air threat which arises from an inexplicable non-human source. Although the complex effects work in the film may look flawed and dated to a modern audience, it’s the way the optical techniques are used which gives these shots their continuing power. A masterpiece of directorial control and the use of cinematic technique to create emotional and psychological effects, The Birds continues to gain stature as one of Hitchcock’s finest films. Beginning as a romantic comedy, it slides quietly into darker territory with the audience barely noticing until it’s too late; the external threat of the birds’ attacks forces the characters to set aside the issues which have constrained their lives – that romantic comedy conflict which begins with antagonism between Melanie (Tippi Hedren) and Mitch (Rod Taylor); the unhealthy emotional attachment between Mitch and his mother, Lydia (Jessica Tandy). The film’s strength lies in the way Hitchcock manages to balance issues of character with the inexplicable environmental threat. It remains the most sophisticated “disaster movie” ever made. (Both included in the five-disk Alfred Hitchcock: The Essentials Collection Blu-ray set from Universal featuring numerous supplements, many carried over from earlier DVD editions)

*

Irwin Allen: The Poseidon Adventure (1972)/The Towering Inferno (1974)

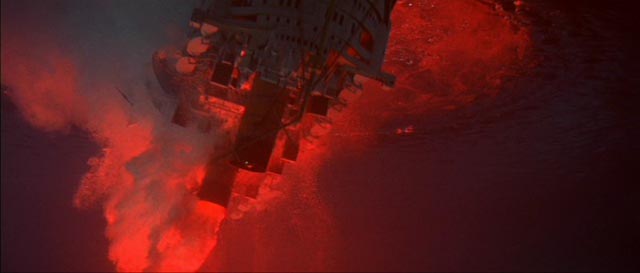

And speaking of disaster, a couple of discount Fox Blu-rays prodded me to revisit two of the quintessential examples of the genre from its heyday in the ’70s. Both, not surprisingly, were produced by Irwin Allen whose misfortune it was the have ambitions as a director; he was much better as a producer. The success of The Poseidon Adventure (1972) launched the genre, establishing a formula which still shapes movies today. The vicarious thrill of watching a multi-character story about ordinary people fighting to survive catastrophe has an appeal for audiences who certainly wouldn’t want to experience these events in person. One characteristic of these films is the cliched shorthand of character, a reliance on stock relationships and conflicts which the cast must struggle to breathe life into. There are performers in Poseidon, and its follow-up The Towering Inferno (1974), who manage to retain their dignity and even evoke audience sympathy. But what really matters in these movies is the details of the disasters themselves and this was where Allen’s real strength lay.

Seen today, the real pleasure of these movies comes from the physical reality of their production; the big, elaborate sets, the actors working surrounded by water and fire and genuine physical risk. I know I keep harping on this difference between physical reality and computer generated imagery, but even if it works on the viewer only on a subliminal level, that material quality has an impact (something still recognized by some filmmakers: Christopher Nolan relied as much as possible on practical effects and fully realized sets rather than green screen on Interstellar and it gives that film a presence absent from, say, J.J. Abrams’ tedious Star Trek movies with their overblown CG action sequences). These movies are far from art, though in both cases they are very well crafted by Allen and his directors (Ronald Neame on Poseidon, John Guillermin on Inferno); their appeal lies largely in process rather than character and narrative, the detailed depiction of making your way through an overturned ship or finding your way out of a burning highrise. (Both on Blu-ray from 20th Century Fox, with numerous supplements, including commentaries)

*

Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (Irwin Allen, 1961)

As a director, Allen was a good producer. He could put together casts, build sets, commission often quite impressive special effects. What he wasn’t very good at was using the camera to tell a story in an imaginative way. Working frequently with former Hitchcock collaborator Charles Bennett (who scripted some of Hitch’s finest British films), Allen directed a handful of movies in the late ’50s and early ’60s before launching a very successful television career (Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, Lost in Space, The Time Tunnel, Land of the Giants), beginning with a genuine oddity: The Story of Mankind (1957), a movie as silly as it was ambitious. His 1960 adaptation of Conan Doyle’s The Lost World is famous for its use of optically enlarged lizards, shot in slow motion, with various fins and horns glued on them, instead of using stop-motion model work to create effective dinosaurs (a technique also used in Henry Levin’s Journey to the Center of the Earth [1959], where it was less detrimental because the film itself was made with more wit and style). After the success of Poseidon and Inferno, Allen again felt the urge to direct, resulting in the dire killer bee movie The Swarm (1978) and the lame sequel, Beyond the Poseidon Adventure (1979).

However, his most notable project as director was Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (1961), largely because it launched the popular TV series which ran for four seasons between 1964 and 1968. I can remember enjoying the TV show, with its monster-of-the-week plots, but in retrospect I think my response to it was coloured by the fact that I first encountered it in the Mad Magazine parody Voyage to See What’s on the Bottom (wouldn’t it be great if someone collected all those Mad movie and TV parodies into one big omnibus volume? – they constituted a very funny and often very perceptive form of contemporary media criticism). I haven’t seen any episodes of the series in decades, but if it really was anything like the feature, my memory at this point is quite misleading.

The feature was an attempt to create a piece of epic science fiction before the genre flowered a few years later with a number of serious, and well-made, features like Robinson Crusoe on Mars, Planet of the Apes, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Colossus: The Forbin Project, Quatermass and the Pit. Allen’s film, although no doubt popular at kids’ matinees, fails on most levels, even in the colourful Blu-ray rendition offered by Fox. The science is risible, the drama both anemic and overwrought. Admiral Nelson (Walter Pidgeon, replaced by Richard Basehart in the series) has built the futuristic nuclear sub Seaview against heavy political opposition. (I wonder whatever happened to the Aurora model kit I painstakingly glued together in my adolescence?) On its maiden voyage under the Arctic ice, it’s out of contact with the surface for several days; when it resurfaces the crew discover that catastrophe has overtaken the world – the Van Allen radiation belt has caught fire and global temperatures are rising rapidly. How this happened remains unexplained (the Van Allen belt is formed by charged subatomic particles held in place by the Earth’s magnetic field).

Nelson and his scientific sidekick Lucius Emery (Peter Lorre) figure out that what’s needed is a nuclear missile fired into the belt to “blow it out”, but the tedious bureaucrats at the U.N., led by the pompous French scientist Dr. Zucco (the great Henry Daniell), insist that we must just wait for it to burn itself out. Against orders, Nelson takes the Seaview and heads for the Pacific to reach the optimum launch site before it’s too late. With U.N. Subs on his tail and a crew which becomes more rebellious as fatalism about the end of the world sets in, Nelson and Emery end up standing against everyone, including Captain Lee Crane (Robert Sterling, replaced in the series by David Hedison, perhaps best known as The Fly) and psychologist Dr. Susan Hiller (Joan Fontaine), who’s on board to study stress among the submarine’s crew. Needless to say, Nelson is right and he saves the world at the last minute – but not before the sub has to navigate an inexplicable and very dense minefield (the old rusty mines apparently left over from the Second World War) and fight off a giant octopus.

The submarine sets are rather dull, the character conflicts contrived; the two women on board (the other being Barbara Eden as Nelson’s secretary and Crane’s fiancee) both run around in high heels; and the effects are uneven. Some of the shots with the burning sky, particularly an effective view of the sub sailing into New York harbour, are quite impressive; and the sub itself looks quite good as it passes beneath an ocean surface reflecting the blaze above. But there are too many thoughtless details: the inhabitants of the sub are first alerted to the disaster when they sail into a whole mess of sinking ice which is breaking off the polar cap because of the heat; for some reason regardless of what the characters say about the sub’s position and depth, exterior shots more often than not show it in the water nose down at a forty-degree angle, no doubt because it looks more dramatic on screen that way, even though it’s supposed to be sailing straight ahead. (The first sight of the Seaview has it erupting from the water like a missile, a manoeuver which would no doubt have caused a heck of lot of injuries among the crew.)

Perhaps the most amusing thing about the Blu-ray is the inclusion of a featurette which tries to situate the film in the history of the genre and then uses the ludicrous premise as a launchpad for a discussion of global warming. If right-wing climate-change deniers ever get hold of the disk, they can use it to debunk the science! (Fox Blu-ray, with two brief featurettes and a fannish commentary)

*

Fantastic Voyage (Richard Fleischer, 1966)

Another Fox Blu-ray, picked up at a deep discount at the same time as the three Allen disks, fares a bit better: Richard Fleischer’s Fantastic Voyage (1966). Ambitious in conception, this tour of the interior of a human body is colourful but not terribly convincing (apart from issues of scale, it seems way too bright inside the body of comatose scientist Jan Benes [Jean Del Val]). The premise is a pretty good sci-fi conceit – a medical team must be miniaturized in an experimental sub in order to operate on an otherwise inaccessible blood clot deep in the scientist’s brain – and it affords the occasion for a few lessons in human anatomy. To spice things up, a security agent is sent along because one of the team members is suspected of being an enemy agent determined to sabotage the mission. Naturally there’s an attractive woman along (Raquel Welch), mainly there to look good in a wet suit.

The mix of sets, miniatures and blue screen keep Fantastic Voyage moving quickly enough that you aren’t tempted to think of all the holes in the science and the plot, but some of the optical work looks pretty crude now. Still, some of the visuals are quite attractive and the story remains engaging. There is, however, one major script problem which seems unforgivable: the film’s ticking clock is provided by the rather artificial conceit that the miniaturization process only lasts for an hour, after which sub and crew will revert to normal size with obviously dire consequences for the patient. Yet at the end, after the saboteur crashes the sub in the brain, drawing the attention of antibodies and white corpuscles, the rest of the crew leave the wreckage behind and escape along the optic nerve, emerging through the tear duct at the very last moment. No explanation is given, however, as to how the sub and the dead bad guy are prevented from reverting simply because they’ve been enveloped by those antibodies – the shrunken atoms which comprised them are still there in Benes’ head, and yet unlike the rest of the crew, they don’t grow back to full size. That bugged me even as a kid when I first saw the movie in a theatre and it still doesn’t make sense. (Fox Blu-ray, with two featurettes and two commentaries)

To be continued …

Comments