Sci-Fi Savant by Glenn Erickson: book review

I’ve been reading, and appreciating, the DVD Savant on-line column for years. Apart from Glenn Erickson’s almost terrifyingly prolific output, it’s the scope of his work that impresses. He writes in an accessible, conversational style, and yet avoids the superficiality which a lot of web-based criticism is prone to. He has a remarkable knowledge of background detail on filmmakers and individual productions, which he combines with observant critical skills and a willingness to address such often overlooked or avoided things as social, historical and political context, the implications – rather than just the details – of a film’s content.

In the introduction to his new book, a collection of 116 of his reviews from the past 13 years of on-line writing, he states that his interest in science fiction movies lies in what they have to reveal about social issues and the ideologies which underlie their stories. Sci-Fi Savant (Wildside Press) is a useful companion to Bill Warren’s classic of the genre, Keep Watching the Skies. While Savant’s book has less depth (Warren packs his essays with interviews with participants and surveys of contemporary critical responses), it is broader in scope, covering films from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927; the opening essay is on the recent almost-complete restoration) to James Cameron’s Avatar (2009), while Warren’s focus is strictly on the ’50s (well, up to 1963). Sci-Fi Savant offers a historical context into the centre of which Warren’s work can be comfortably slotted.

In the introduction to his new book, a collection of 116 of his reviews from the past 13 years of on-line writing, he states that his interest in science fiction movies lies in what they have to reveal about social issues and the ideologies which underlie their stories. Sci-Fi Savant (Wildside Press) is a useful companion to Bill Warren’s classic of the genre, Keep Watching the Skies. While Savant’s book has less depth (Warren packs his essays with interviews with participants and surveys of contemporary critical responses), it is broader in scope, covering films from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927; the opening essay is on the recent almost-complete restoration) to James Cameron’s Avatar (2009), while Warren’s focus is strictly on the ’50s (well, up to 1963). Sci-Fi Savant offers a historical context into the centre of which Warren’s work can be comfortably slotted.

While Savant gives time to many of the major titles of the genre, he also offers coverage of more obscure films, including ones not readily available on DVD – Abel Gance’s Le Fin du Mond (1931), which sounds like an interesting disaster; Vasili Zhuravlyov’s Kosmicheskiy reys (aka Cosmic Journey or The Space Voyage, 1936 – I actually have a gray market copy which I bought on-line some years ago from Mechanoise Labs); and Karel Zeman’s The Fabulous World of Jules Verne (1958). With more than one hundred reviews, this volume allows him to cover most of the major titles in the genre, plus interesting low budget items and a few buried treasures … and most importantly, whether you already know the film or have merely heard of it, or it’s entirely new to you, these short essays will spur your interest and make you want to see it …

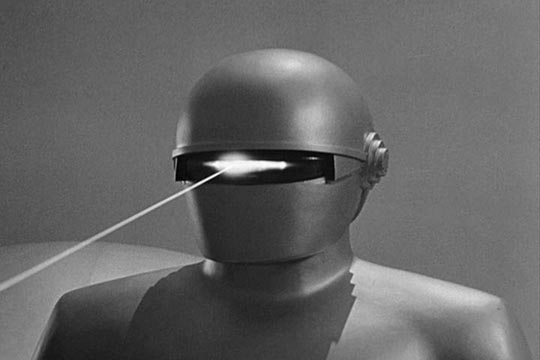

His readings of standards like Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) and Robert Wise’s The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) bring out these films’ ambiguities. Siegel’s film famously can be interpreted either as a vision of communist takeover or as a warning about mindless conservative conformity. What is less frequently acknowledged is the central confusion in Wise’s movie, which is generally viewed as a pacifist work. But Savant dissects in detail all the problematic aspects of the plot and theme, what amounts to a call for fascism dressed up as a religious parable. Yet he still has no reservations about its status as a classic within the genre, and its emotional force as a narrative.

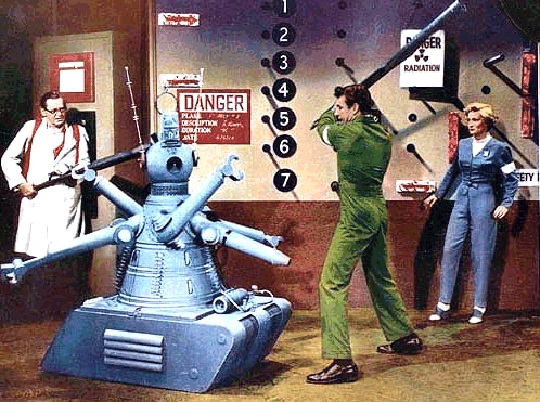

Not surprisingly, almost half of the movies dealt with come from the ’50s; also not surprisingly, that 45% represents most clearly the collective view of what defines the genre – space exploration, fear of technology, giant insects, giant monsters and atomic destruction. In Roger Corman’s Teenage Caveman (1958) and Edward Bernds’ World Without End (1956), a few survivors face the aftermath of nuclear war; in Herbert L. Strock’s Gog (1954, shot in 3D), enemy agents control a top secret super computer in an attempt to sabotage the development of new U.S weapons which would give the States military dominance over the world. Fear of threats both internal and external predominate. One of the oddest manifestations of the decade’s fears is Harry Horner’s red scare revivalist curiosity Red Planet Mars (1952); here God actually intervenes by radio to bring down the Communist Empire and establish a world-wide Christian theocracy. I did a quick search after reading Savant’s comments and found a copy on line in two parts at Google Videos, which I immediately watched – far more entertaining than I’d expected! (That one has long since vanished, but the movie is now available on YouTube here.)

In fact, it’s a rare SF movie that offers a positive view of science and technology. There’s William Cameron Menzies’ Things to Come (1936) with its final ode to the human urge to explore and grow beyond the petty limitations of superstition and politics; there’s the fairy tale finale of Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) with its reduction of human beings to awestruck children happily giving up responsibility to benevolent cosmic parents. But the poetic conclusion to Jack Arnold’s The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), with its vision of human significance in an infinite cosmos, stands virtually alone – unless you interpret the ending of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) as a visual corollary.

Savant is astute on potentially “difficult” work like Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers (1997) which indeed does appear to wallow in fascist iconography, trusting the viewer to pick up on the satirical purpose. I well remember my own first viewing, at a packed preview screening. I left the theatre stunned, even appalled. I recall trying to describe it to someone the next day and saying something like “It’s the kind of movie Hollywood would be making if the Nazis had won World War Two.” Wait a beat; a light goes on. This is the kind of movie Hollywood makes (just think of the fascist rally celebration at the end of Star Wars; Rambo flexing his muscles and slaughtering half the population of Southeast Asia in his second outing …). It was literally like a switch being flicked in my head, the realization that what Verhoeven and writer Ed Neumier had done was simply to strip away the disguise and show the face of popular mainstream entertainment for what it really is.

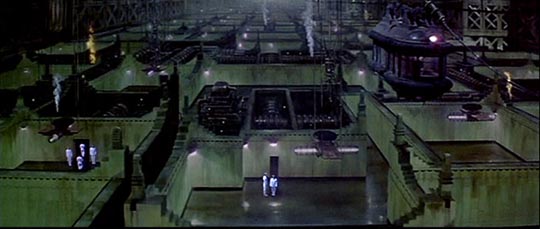

Savant is also willing to see the value in something generally deemed a failure, like David Lynch’s Dune (1984), a huge unwieldy monster crippled by its producer and distributor, yet still one of the most remarkable evocations of science fiction’s fabled “sense of wonder”, a breathtaking depiction of multiple worlds designed down to their last details.

What I like most about Glenn Erickson’s reviews is that for him it’s never “just a movie”; he’s interested in the message as well as the medium, and he’s deft at illuminating where and how a particular movie fits into the flow of film history as well as into the society in which it was produced. Too many people dismiss the implications of content because they don’t want to think about what’s really being sold to them; Savant always wants to look under the hood.

If I might have one quibble about this compilation of essays, it’s that the book retains the “disk review” aspect from the DVD Savant website. As with any “consumer guide”, these comments are likely to date far more quickly than the critical evaluations of the movies themselves. Those evaluations will remain relevant as long as we have access to these movies in whatever form technology is going to throw at us next.

Comments

Beware of Glenn Ericksons reviews. The man seems incapable of reviewing any film without interjecting radical Leftist views. Everything appears Racist, Sexist and Capitalist to Erickson. Any film, no matter how harmless or apolitical, will be reviewed from a perspective of Leningrad, circa 1934. And to post critical analysis on his site means instant and permanent banishment.

Thanks for the morning laugh. Culture is permeated with politics and ideology … it’s a good sign that the Right, which has managed for many decades to define its biases as the invisible norm, seems increasingly panicked about having those biases exposed by people who are now more willing to point out how the majority have been getting abused by the privileged minority. Ideology is embedded in all human activity; to point out how it works even in “simple entertainment” is a valuable service provided by people like Glenn.