Recent viewing, part 1

Since reading Chris Fujiwara’s book about Jacques Tourneur, The Cinema of Nightfall (Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore and London, 1998), I’ve been searching out films by the director, particularly ones unconnected with the genres he’s best known for, horror and noir. I recently got hold of a cheap VCI disk featuring a double bill of RKO Technicolor adventure movies – Tourneur’s Appointment in Honduras (1953) and Allan Dwan’s Escape to Burma (1955). Neither is particularly remarkable, both largely shot on studio jungle sets with a bit of location footage to add a slight sense of scale.

Appointment in Honduras starts on board a steamer, with American Jim Corbett (Glenn Ford) urgently checking with the radio officer about messages from a man identified as the recently deposed Honduran president. When the captain informs him that the ship won’t be putting into port because of the political unrest, Corbett frees five prisoners from the hold and takes two passengers hostage, heading for the coast in one of the lifeboats. A vague triangle is established between Corbett and the hostages, a troubled married couple (Ann Sheridan and Zachary Scott). The husband constantly tries to stir up trouble between the convicts and Corbett, while the wife gradually finds herself attracted to the adventurer. Along the way to Corbett’s rendezvous, they face the usual jungle hazards – stock shots of crocodiles, snakes in trees, swarms of bugs (a rather poor animation effect), armed police, and carnivorous fish.

Tourneur’s film features several of the motifs analyzed by Fujiwara, particularly the ambiguity of character motivations and the tenuous nature of information; some importance is made of certain facts withheld by Glenn Ford’s protagonist about his purpose and just where he’s leading the party in the jungle … but as the story progresses, those secrets seem to evaporate, leaving little impact on events. What was important to the character ultimately plays little part in the story. It all ends with a shootout in a deserted village, with Corbett finally revealed as a noble man, paving the way for a relationship with the now widowed Sheridan character.

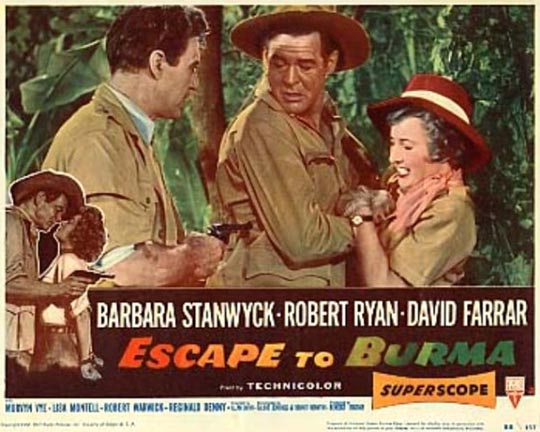

Dwan’s Escape to Burma has Robert Ryan on the run, having been accused of killing a prince he was in the mining business with. He hides out at the teak plantation of Barbara Stanwyck, where some kind of romance is indicated by the script, though there’s very little heat between the two stars. David Farrar (veteran of four Michael Powell films) is the district colonial police officer sent to bring Ryan in, only to realize when it’s almost too late to stop the execution that the man is, of course, innocent. The three stars are always worth watching, but none of them can work up much enthusiasm for the routine script.

*

Guillermo Del Toro has a peculiar dual career, his great, imaginative Spanish fantasies (Cronos, Devil’s Backbone, Pan’s Labyrinth) interspersed with bigger-budgeted Hollywood genre movies (Mimic, Blade 2, Hellboy). There are visual/stylistic connections between the two strains, but in terms of content, theme and emotional impact, the US movies are bigger, flashier, and emptier. As with many foreign directors lured to Hollywood, it seems that what makes his films so distinctive ends up being the thing that his American producers don’t trust and try to squeeze out of the work. Mimic (1997) is a nicely designed, somewhat sluggish and only intermittently engaging big bug movie. Three years after a genetically engineered bug is released into New York’s sewers to wipe out plague-carrying cockroaches, it emerges that the supposedly sterile strain has mutated into giant smart bugs capable of disguising themselves as humans – in other words, strictly B material (based on a Donald A. Wollheim short story). But what makes the Blu-ray of the director’s cut worthwhile is Del Toro’s commentary track. He himself recognizes that the movie is in many ways an unimaginative failure, but surprisingly he goes into great detail about the evolution of the film and the process by which his many producers whittled away at the script, draft by draft by draft, until almost everything that interested the director about the material, all the quirky ideas and details, was stripped away in an effort to make the final product as formulaic and unsurprising as it could be. But Del Toro doesn’t use this opportunity to rail against the stupidity of Hollywood; he analyzes the ways in which this brutal, dispiriting process actually helped him to hone his directorial skills and find ways to navigate the complex politics of studio production. Although Mimic remains one of the least interesting works he’s created, after hearing his story of its making you can’t help but feel a little bit of respect for what’s visible on screen.

*

The Ark (1993) is the second volume of the BFI’s series of DVDs devoted to the work of Molly Dineen. A four-hour BBC documentary about a year-long management crisis at London Zoo might sound like a bit of a chore to sit through, but Dineen’s engagement with the people involved on both sides of the fight and her wonderful eye for telling details create a dramatic epic which embodies a whole range of issues faced by a venerable institution dealing with radically changing ideas about its purpose while in the midst of a larger social shift to a more strictly economic view of all activity in the wake of the Thatcher “revolution”. As a new management team works to “streamline” the zoo – getting rid of thousands of animals and dozens of keepers in order to save money, while refocusing on the zoo’s “entertainment” function – the employees (many of whom have been caring for and studying the animals for decades) fight not only to keep their own jobs, but to salvage some of the zoo’s original purpose as a research centre which they see as having renewed purpose as species endangerment increases around the globe. Dineen’s openness and interest in everyone involved prevents any easy sliding into a good guys/bad guys formula; evoking sympathy for figures on both sides of the struggle, she raises important questions about the intricate connections between social, scientific, personal and economic purposes. The result is an epic somewhat reminiscent of Frederick Wiseman‘s finest observational studies of institutions.

*

Ken Loach did a lot of work at the BBC during the first part of his career, and a massive six-disk, 18+ hour set was recently released in region 2, containing a selection of his Wednesday Play (1965-69) and Play for Today (1971-77) productions, along with the four-part Days of Hope (1975). So far, I’ve only had time to watch the first disk, containing Three Clear Sundays (1965) and The Big Flame (1969).

The latter is a docu-drama about a dock strike, surprisingly made during the final year of the Labour government of Harold Wilson, though prescient about the social shifts which would come ten years later with Thatcher’s rise to power. Faced with pressure by the government and management to “streamline” the docks – i.e. lay off large numbers of workers – the union digs in and the men occupy the docks and start running the business themselves. Although there are stresses and some internal conflicts, the workers make their point that the docks can be run smoothly without the presence of overpaid managers; but despite the fact that ships are being loaded and unloaded and goods are being moved, the government cracks down on the “disruption” and moves in with the police and the army, arresting the leaders and reestablishing “order” – no doubt paving the way for management to go ahead with massive layoffs. Shot in black and white, this rough-edged play wrings quite a bit of narrative tension from lengthy, confrontational meetings, and clearly establishes Loach as the leftist polemicist who has continued to hammer away at social issues for the subsequent forty years.

The earlier Three Clear Sundays also has a polemical purpose (coming down firmly against capital punishment), but uses a less direct approach. The not very bright son of an East End family involved in petty crime tends to act without thinking. He’s got his Irish Catholic girlfriend pregnant (much to his Mum’s disgust) and one day gets into a casual argument in the local pub. Unfortunately, the belligerant man he hits is a policeman. Against his mother’s advice, he simply pleads guilty and gets sentenced to six months. Inside, his simplicity seems perfect to his hardened cellmates who talk him into knocking out a guard so that they can get reduced sentences for “saving” the man. Unfortunately, he hits the guard too hard and the man dies … leading to a conviction for murder and a death sentence. Loach approaches this story like a folk tale – or rather a folk song. The narrative is interspersed with ballads that comment on the action, creating an air of almost mythic tragedy, while the characters (particularly Rita Webb as Mum) remain vivid, convincing types.

*

Set against the bleak social commentary of Ken Loach, volume 5 of the BFI’s Central Office of Information series, Portrait of a People, has an almost smug tone of self-congratulation in its odes to the English character and way of life. We see ordinary people committed to public service as village councilors; a devoted small-town newspaperman diligently reporting on local farm news; the vibrant productivity of an industrial town; and the activities of people in their leisure time. Looking back from our perspective, perhaps the most interesting film in the set is Moslems in Britain: Cardiff (1961), a relentlessly upbeat tour of the Welsh city by Gamal Kinnay, an immigrant, who drops in to talk to Muslims in various parts of town – labourers, a local Imam teaching a class of mixed-race children Arabic so that they can read the Quran, the English wife of an Arab man who seems to speak Arabic well. Everyone is cheerful and says that Cardiff is a fine and welcoming place for immigrants. Made in 1961, the film was designed specifically to be shown in the Middle East as part of an official effort to attract Arab workers to help alleviate the continuing post-war labour shortage, but given the evolution of racial and cultural tensions in the subsequent decades its tone now seems almost impossibly naive.

*

The Savage Eye (1960) is a collaboration between Ben Maddow, Sidney Meyers and Joseph Strick. A woman (Barbara Baxley) arrives in LA to wait out the year before her divorce comes through. As she gets off the plane, a male voice (Gary Merrill) begins to speak, declaring that he’s her guardian angel. Shot MOS, the only dialogue in the film is the running voice-over conversation between the “angel” and the woman. As she goes about her routines – collecting her mail, visiting a beauty parlour, a gambling hall, a restaurant, eventually going on dates – the two voices ruminate on loneliness and isolation; bitter, she’s repelled by human contact, struggling with an older man as he tries to paw and kiss her in a night club. The film is fascinated with the ways in which people gather together to gain some sense of community and belonging, lingering on the crowd reactions at a wrestling match, at the dancehall where the woman fights off her date, and finally in a lengthy sequence at a fundamentalist revival meeting with the laying on of hands, healing, speaking in tongues … It all drives the woman into a state of despair; distracted, she crashes her car, seems to die … but reemerges with a sense of resignation and acceptance. Although I’m sure the filmmakers wouldn’t be flattered by the comparison, what The Savage Eye reminded me of most was John Parker’s Dementia (aka Daughter of Horror, 1953/1957). Although Parker’s expressionist camera is replaced here by a hard documentary eye, the sense of turmoil leading to despair and bordering on madness seems quite similar, an impression aided by the exclusive use of voice over with its echoes of Ed McMahon’s ominous narrator in the Daughter of Horror version. Despite some minor scratches and speckling, the print used on the French Carlotta DVD is in very good shape, with deep blacks and rich contrast, and the transfer is excellent. Extras include an interview with Strick about the making of the film, and his short Oscar-winning documentary Interviews with My Lai Veterans (1971), a chilling look at how ordinary men not only come to take part in atrocities, but process them afterwards so that they can go on living with themselves – distancing the events (“others did the worst”) and, disturbingly, claiming that they were “just following orders”. How easily the fascist dehumanization which marked Nazi Germany can take root in a democracy …

Comments