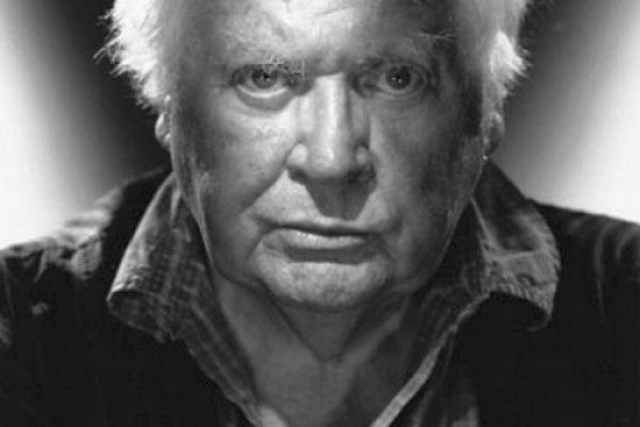

Ken Russell (1927-2011)

Although I no doubt had read about Ken Russell‘s film of D.H. Lawrence’s Women In Love (1969) when it was released, I didn’t see it until some years later. My first real memory of him is from late 1970 or early ’71. I was living in Newfoundland then and my mother still subscribed to a couple of English newspapers, one of which (for some odd reason, now lost in the mists of time) was the tabloid Daily Mirror. Every week we received a fat, rolled up week’s worth of issues bound in a yellow cover. And in one issue, there was an “appalled and outraged” article about the filming of The Devils (1971), complete with a photograph of a group of apparently writhing, naked nuns. The article’s focus was a supposed incident in which an underage boy was reported to have been involved in filming said writhing, naked nuns, the shot ending with him flopped down with his hand on a bare breast. Obviously, the filmmaker was a despicable pornographer.

Of course, being 16 years old, I was eager to see The Devils and in fact went at least twice when it showed up in St. John’s. It was unlike anything I’d previously encountered, a richly designed (by Derek Jarman) vision of history steeped in madness, so intense that you almost felt you were choking on it. Not a film you could quietly sit back and contemplate, but one that rolled over you and sucked you in, forcing you to confront and come to terms with some truly awful aspects of human behaviour. I loved it.

It was that choking air of madness that offended a lot of people. It made you uncomfortably aware of how tenuous our own hold on sanity could be. But, despite much of the criticism aimed at the film, there was far more going on in it than a wallowing in mere sensation. The film is incisive in its dissection of the connections between political power and the manipulation of religious conviction, the way in which such convictions can be used to control and destroy obstacles to the exercise of power.

Russell, who died on November 27 at the age of 84, was a “lapsed” Catholic, but much of his work is infused by his conflicted relationship with his own religious upbringing. And at the heart of The Devils, packed as it is with vile hypocrisy and Church-sanctioned brutality, is a dramatic story of sin and redemption. Urbain Grandier (Oliver Reed) is himself a hypocrite, a priest who uses his position to seduce sheltered young women, very much a man of the flesh who indulges his animal appetites to the limit. But he is also politically aware and when Cardinal Richlieu, intent on consolidating the power of the French state, decrees that the walls of all fortified towns are to be torn down to prevent opposition to the crown, Grandier stands up against the threat to Loudun’s autonomy. An outbreak of hysteria in a local convent provides the authorities with a weapon against the outspoken priest, and the Mother Superior (Vanessa Redgrave) is manipulated into accusing Grandier, who snubbed her request to become the nuns’ confessor, of consorting with the devil and instigating an epidemic of demonic possession.

The sexual hysteria which has infected the convent is whipped up into an ever greater frenzy by the inquisitors sent by Richlieu to “investigate”; the convent is put on display for the public, supposedly a cautionary lesson in the ways of the devil, but really as a form of entertainment like the later tours of madhouses which were popular among the bourgeoisie in the 18th and 19th Centuries. The chief result is to spread the hysteria beyond the convent, to infect the surrounding community to the point where only a grand public sacrifice can break its hold. Thus the ritual torture and execution of Grandier by burning at the stake. It’s here that Russell’s Catholic roots show most clearly; while appalled at the corruption of the Church, the depiction of Grandier’s transformation into a Christ-like figure, his body scourged of its animal desires so that his spirit can grow in stature, becomes a lesson in how the individual can become transcendent, achieving spiritual purity while taking on the sins of his fellows. The final images of the film show the earthly triumph of the political schemer Richlieu, the walls of Loudun being demolished now that Grandier’s opposition has been crushed … but for Grandier himself, the individual man, spiritual salvation has been achieved.

While a kind of madness runs through much of Russell’s work, he never again attained this level of intensity. The story of Grandier brought out something deep in him which was tied to his own religious issues. Much of his other work was secular in nature, focused on artists and creativity – another form of madness. He was constantly striving to evoke the pain and ecstasy involved in artistic creation, starting with his remarkable series of composer biographies for the BBC programs Monitor and Omnibus (1962-70). Sometimes he stumbled into thickets of kitsch (the deliriously entertaining Lisztomania [1975]), at other times he distorted history in his search for psychological authenticity (the exhilirating Mahler [1974]). What tended to appall his critics was his willingness to risk going over the edge, a “tastelessness” which offended propriety. In this, he was not so unlike another great English director, Michael Powell, himself given to a kind of delirium which often evoked cries of tastelessness. Russell also resembles that other great artist of madness, Andrzej Zulawski, who digs deep for emotional truths at the expense of polite comfort.

I, like many others, have been waiting a very long time for Warner Brothers to release a definitive edition of The Devils, hoping against hope that this could be done while Russell was still alive so that he could provide a commentary to his greatest film. Well, the BFI has announced that it will bring out an edition next Spring. Whether it will be definitive, or whether they managed to get that commentary track before Russell died, remains to be seen. But I’ll definitely be ordering a copy.

*

Note (12/31/11): Amazon UK has posted the following list of special features for the release, which certainly make it look like everything one might have hoped for (although it appears to be DVD only, no Blu-ray):

Special Features*

- DVD premiere presentation of the original UK X certificate version

- Audio commentary with Ken Russell, Mark Kermode, Mike Bradsell and Paul Joyce

- Hell on Earth (Paul Joyce, 2002, 48 mins): documentary exploring the film’s production and the controversy surrounding its original release

- Director of the Devils (1971, 21 min): documentary featuring candid Ken Russell interviews and unique footage of Sir Peter Maxwell Davies recording his celebrated film score

- Original on-set footage with commentary by editor Mike Bradsell

- Amelia and the Angel (Ken Russell, 1958, 30 mins): Ken Russell’s short film, a delightful mix of religious allegory and magical fantasy

- Original UK trailer

- Original US trailer

- Fully illustrated booklet featuring new essays and notes from Mark Kermode, Craig Lapper (BBFC), Sam Ashby, and others

Comments