Reviewing documentary

A while back, I signed up with BlogCritics. The idea was that writing regular reviews for them would keep me from getting lazy; in addition, cross-linking with my blog would, I hoped, boost traffic for my own site. But I’ve only posted four reviews with them since February, while keeping up a regular weekly schedule on my own blog.

The chief reason for this (apart from a couple of annoying editing incidents) is that I don’t really like writing reviews. As regular readers of this blog may have noticed, I usually use a particular DVD as an excuse to go off on tangents about more general subjects.

I recently found the constraints of writing a review for BlogCritics quite frustrating when I was obliged to deliver a post about Athena’s new three-disk set, The Making of the President: The 1960s (I had scored the review copy, so had no choice but to come up with something). What generally separates a review from an “opinion piece” is the necessity to frame what you say as some kind of consumer report (I can’t, for instance, write about a film on Blu-Ray for BlogCritics because I don’t have a studio quality HD television and so can’t write about the particular technical qualities of the product, which often seems to be the main subject of Blu-Ray reviews).

From a hi-def consumer point of view, the Making of the President set has little to recommend it. The video and audio quality of the three feature-length programs (produced for television by David L. Wolper) is generally pretty poor – they are essentially made out of archival TV news reports, the earlier material mostly shot on 16mm black-and-white film, much of which is battered and scratched; the later material, shot on video, is all muddy colours and soft, smeary images; the sound is frequently garbled and distorted.

So, from a consumer point of view which increasingly focuses on technical quality before content, the set is a bit of a disaster.

From a strictly content point of view, however, the set is interesting … but also endlessly frustrating.

In narrative filmmaking, whether fiction or documentary, there are two main points of focus for a review: the story being told and the way the story is told. In fiction film, the two are deeply implicated with one another – meaning arises from the way in which the story is being told.

In documentary, this is also true to some degree (just look at the work of the Maysles Brothers), but “informational purpose” can make aesthetics seem less relevant or important. In fact, strong aesthetic elements can actually problematize the material (the “documentaries” of Leni Riefenstahl, for instance). When it comes to documentary, a powerful or important subject can render aesthetics unimportant, although careful crafting can certainly enhance the impact of the information being presented, while egregious techniques can actually undermine otherwise powerful material (hello, Michael Moore).

So, with the Making of the President set, I had three separate elements to juggle in my review (which I’m afraid I didn’t manage very well!): the surface technical quality of the presentation, the historical narrative being presented, and the method of that presentation.

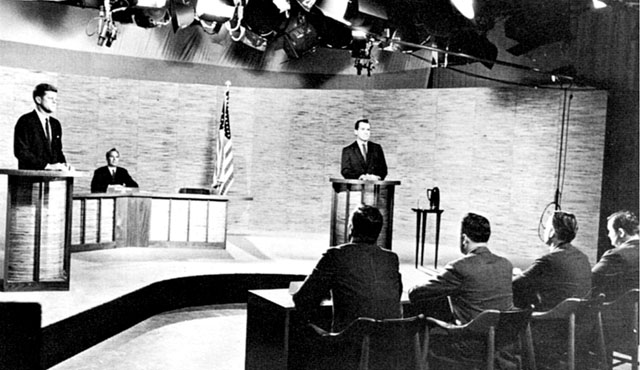

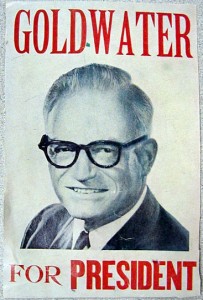

The problems with the first of these have already been mentioned. The interest of the set resides squarely in the second aspect, the narrative which spans the three presidential elections of the ’60s. Here we see the foundations being laid for the subsequent political history of the United States. Coming out of the successfully conservative Eisenhower ’50s, large shifts were beginning to take place, crystallizing in 1960 with the contest between Kennedy and Nixon. From our perspective, seeing the current rigid partisan split in American politics, it’s interesting to note that there was a left-right spread in both parties back in 1960. Kennedy had to compete for the Democratic nomination against the leftish internationalist Adlai Stevenson, while Nixon was in a three-way contest which included the “radical” Nelson Rockefeller and the far right Barry Goldwater. Nixon, the “moderate”, got the Republican party nod.

By 1964, Johnson had established a solid legislative record, particularly in the area of civil rights. Opposing him was the intransigent Goldwater, who viewed all such legislation as a violation of States’ rights and an imposition by the government on individual freedoms. Goldwater built a powerful grassroots campaign and much of his rhetoric sounds very much like that of the Tea Party today. The electorate rejected his position by choosing Johnson in a landslide.

But by 1968, with the country bogged down in Vietnam, race riots in the streets, the assassinations of Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King, and the burgeoning anti-war movement, Johnson had squandered his political capital and chose not to run for re-election. In disarray, the Democratic party was split between the youth-leaning Eugene McCarthy and Johnson’s vice-president, Hubert Humphrey, who seemed to stand for the old guard and carried the burden of the war into the campaign. Bobby Kennedy shook things up when he announced his candidacy, but he was killed on the eve of taking the lead and by the time of the convention in Chicago, with virtual war in the streets between Mayor Daley’s cops and the anti-war protestors, Humphrey took the nomination.

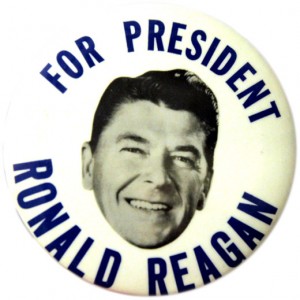

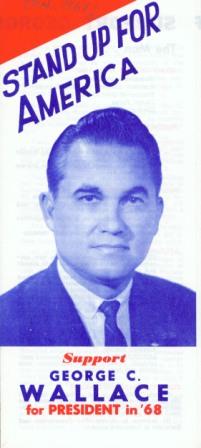

Once again, Nixon found himself between the right and the left in the Republican race, with Rockefeller again running against him and Reagan joining from the right. Rockefeller had popular support, but was distrusted by party insiders, while Reagan pushed the law and order agenda with calls for crushing popular protest. Once again, Nixon came across as the reasonable moderate – an image only reinforced by George Wallace’s entry into the presidential contest. But despite the collapse of the Democrats and pressure from the far right, Nixon still won with only a small majority.

The divisions which opened up during the ’60s became more rigidly codified over the following decades until, with the present, we reach the bizarre spectacle of two Americas existing side by side yet seemingly inhabiting completely different universes. Back in the ’60s it was still possible for the two sides to communicate in a shared arena; now they appear utterly unable to understand each other’s language.

The value of the Making of the President documentaries lies in this sketch of a vitally important transitional time, both political and cultural, when the seeds of mutual distrust and even hatred were sown.

But as films – that third element, how the story is told – these documentaries are far from satisfying. Based on Theodore H. White’s award-winning series of books by the same name, the films are cobbled together from archival footage, most of which consists of that hastily grabbed, on-the-spot coverage used to illustrate quick stories on the evening news. Such material, referred to as B-roll in the business, is seldom illuminating in itself and generally serves as visual wallpaper to accompany the reporter’s/anchor’s commentary. And that, largely, is how it is used here: written by White himself as if he had no idea of the difference between the screen and the printed page, we get a non-stop barrage of narration which buries everything we see. Even when there are clips in which the candidates actually speak, as often as not the sync sound is suppressed and the narrator tells us what they are saying.

Admittedly, although White and producer Wolper make no bones about their own position as liberals, the films do tend to strike a fairly neutral tone throughout. In fact, what may seem odd with the benefit of hindsight, it’s quite surprising how well Nixon comes across throughout – less the nervous, sweaty, shifty image we remember, but more as a reasonable moderate with a sense of humour, albeit an awkward one.

By the 1968 campaign, the chaos which was seemingly overtaking the country also seems to overwhelm White, and his narrator is occasionally reduced to silence as the material is finally allowed to speak for itself.

None of which is to deny the films’ importance in their own time. They represented that first confluence of television and politics in which both began to exist in a symbiotic relationship; as the media gained power, they also gained access in areas previously hidden from view. These documentaries offered a revelation to the audience, exposing the mechanics of the political process. In the years that followed, it was impossible to put that cat back in the box and now it seems that we have nothing but revelations of what politicians would rather keep hidden. In the 1960 episode, we see the media creating the mythic figure of JFK; since then they seem to spend most of their time trying to deflate self-mythologizing demagogues.

Politics as a practice might not have changed that much in the past century, but the public perception of it has deteriorated catastrophically. The Making of the President: The 1960s, despite many technical and aesthetic shortcomings, gives us a glimpse of the moment when that shift first took place.

Comments

Not bad. Not bad at all!