Dino de Laurentiis (1919-2010)

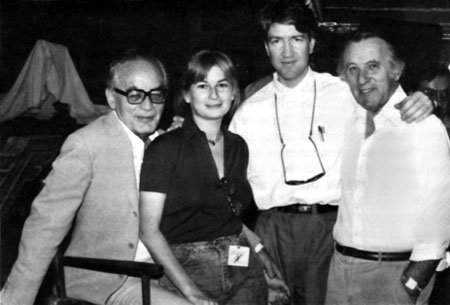

My personal acquaintance with Dino de Laurentiis was very brief. While I was working on David Lynch’s Dune in 1983, I saw Dino a number of times on his occasional visits to Estudios Churubusco in Mexico City. But only once were I and my co-documentarian Anatol Pacanowski introduced to him. We were working in our room on the second floor of one of the administration blocks at the studio when Dino was being given a tour and he and his daughter Raffaella, Dune‘s producer, accompanied by a number of hangers-on, looked in. He was told that we were there shooting behind the scenes of the production. I can’t recall now whether he even said hello, but I do know that he barely gave us a glance before leaving the room and continuing the tour. He was a lord and we were mere serfs …

Dino had a remarkable career, but looking back over his filmography it’s difficult to discern any particular personality in the accumulated body of work. He produced a couple of Fellini’s early masterpieces (La Strada and Nights of Cabiria), but at some point became an international mogul putting together big productions packed with multi-national stars, floating on often bloated budgets which were tied to questionable scripts – the awful remake of King Kong and its sequel, the camp delights of Mike Hodges’ Flash Gordon, the ponderousness of Bondarchuk’s Waterloo, the revered Serpico, the reviled Mandingo and the ridiculous White Buffalo and Orca.

It was certainly very obvious by the time that I met him that Dino was simply a businessman, that his only concern was in packaging projects to feed the marketplace. Which is why his choice of David Lynch to direct Dune is so interesting. Lynch had a very short track record at the time – just Eraserhead and The Elephant Man, both odd small-scale films with good critical reputations but not very big audiences. What reputation Lynch had at the time was as an artist rather than a commercial filmmaker, yet Dune was to be possibly the most expensive film made up to that time. Dino, apparently, nurtured plans for his epic to have artistic credibility at least equal to its box office viability.

It’s unfortunate then that the film was ultimately crippled by the business forces which inevitably had such detrimental material impact on Lynch’s vision. While incredible resources were brought to bear in making the film, what was ultimately released was severely gutted in order to meet the distributor’s contractual demands for a 130-minute cut. This, despite the fact that the script which went into production at the end of March 1983 would obviously make for a considerably longer film. In some ways what was hacked out during the editing process was the heart of the story – the detailed depiction of Fremen culture and its roots in the harsh environment of Arrakis, and Paul Atreides’ appropriation of that culture to fight his war with the Harkonnens and the Emperor. With this mid-section reduced to a mere sketch, what remained was essentially a story about two feuding noble families with a few big battle scenes thrown in.

It’s a pity that there has never been, and probably never will be, an attempt to reconstruct Lynch’s original conception of the film (the “extended cut” made for television was a travesty). But I believe that the time will come when Dune will be re-evaluated and finally recognized for what it does achieve rather than dismissed for its failures. It is still one of the most richly designed of all fantasy films, a work of breathtaking visual textures and, like most of Lynch’s work, it offers the viewer immersion in an imaginary world quite unlike anything produced by any other filmmaker. Undeniably an unfinished edifice, it can still evoke a sense of awe and, in the end, for that we have the often crass Dino de Laurentiis to thank.

Note: a wealth of information about the production of Dune can be found here: www.duneinfo.com.

Comments