DVD of the Week: Loving Memory (1970)

Of the two Scott brothers, I’ve always had a preference for Ridley. No doubt the writers of Cinema Scope would attribute this to my innate middle-brow pretensions, but I’ve never managed to grasp their argument for Tony’s superiority (editor Mark Peranson on Unstoppable: “it is the key Hollywood film of this typically weak quarter, thanks to the typical strengths of Tony Scott’s direction and cutting, the film’s daring, forceful plunges into abstraction combined with a hardscrabble, working-class metaphysics [in this case of a runaway train being run down by an orphan engine chugging in reverse, literally physics].”). A few years back, when I saw and liked Deja Vu, I rented a stack of the younger Scott’s movies and spent a week watching them. I had previously been irritated by the flashy, vacuous style of shallow movies like Top Gun, Days of Thunder, The Hunger, and generally held the opinion that Tony’s work has no substance, no particular theme to convey. But watching many of his films back to back, I quickly came to the conclusion that the stronger the narrative, the more straightforward (and powerful) his storytelling is … and that when the narrative is weak or confused, he piles on thicker and heavier layers of visual excess as if to compensate.

The good movies are great pieces of action filmmaking: Crimson Tide, Enemy of the State, Deja Vu, and more recently The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3 and Unstoppable. Then there are the middling ones where he seems more to be marking time, like The Last Boy Scout, Beverly Hills Cop II and The Fan, while at the other end of the scale he goes into such a visual frenzy trying to breathe life into weak material that we end up with the seizure-inducing overload of Man On Fire and Domino.

Although I find quite a few of Tony’s movies tedious and uninteresting, the ones I like I like quite a lot. So, when the BFI announced the release of the only two films he ever made in his native England, One of the Missing (1968) and Loving Memory (1970), I was interested in taking a look.

What I got was completely unexpected.

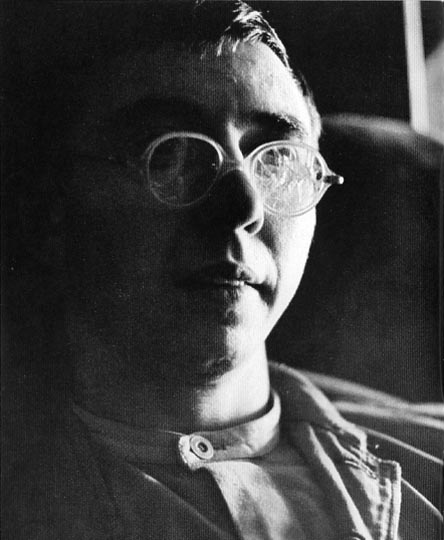

Tony Scott studied fine art at Sunderland College of Art and Leeds College of Art, intending to become a painter. While at Leeds, having starred in brother Ridley’s first film, Boy and Bicycle, which had received some funding from the BFI, Tony approached the Institute to back his own first film. The result, One of the Missing, made for very little money, is an impressive half-hour adaptation of an Ambrose Bierce short story (quite reminiscent of Robert Enrico’s An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge [1962]). Shot in Yorkshire countryside standing in for Virginia, Missing, like Owl Creek, is one of Bierce’s nightmarish Civil War stories in which a lone protagonist confronts and comes to terms with his own death; in this case, a scout finds himself buried under rubble when a Union unit shells the wall he’s hiding behind. When he comes to, he discovers that the muzzle of his own rifle is just inches from his face, but he’s so tightly pinned that he can’t move. As in Enrico’s film, his racing mind conjures up a series of alternate events in an attempt to escape the inevitable, but reality keeps dragging him back. In the end, he just manages to use a piece of wood to press the trigger and put an end to the situation.

Scott wrote the script, produced, directed, photographed (in 16mm black-and-white) and edited the film, already revealing a talent for fragmented montage, psychological effects heightened by expressive techniques. But there’s still an element of conventionality in the choice of subject and the manner of execution – perhaps resulting from the inevitable echoes of Enrico’s masterpiece.

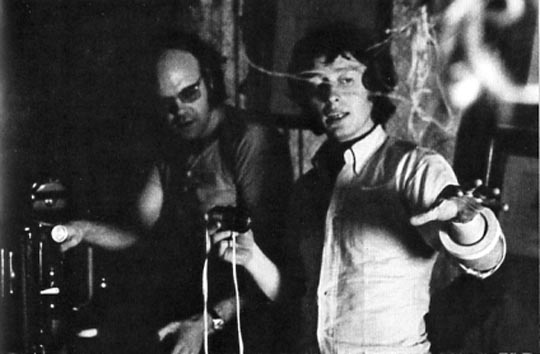

What followed is far more original and stands as something quite unique in Tony Scott’s oeuvre: Loving Memory. While again writing, directing and editing himself, this time he hired the great cinematographer Chris Menges to shoot in 35mm and the result is a luminously beautiful, incredibly sad film which has the flavour of a fairy tale with horrific undertones.

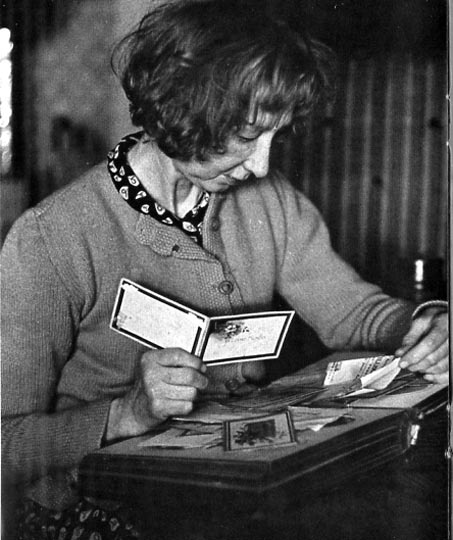

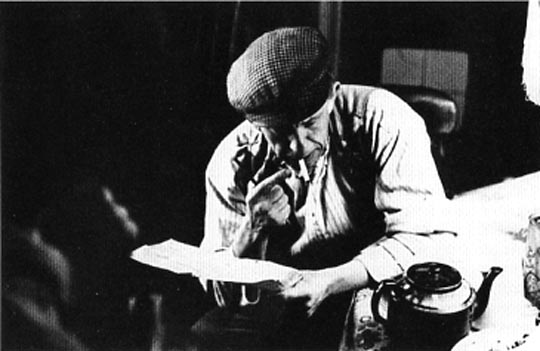

Loving Memory begins with a cyclist being struck on a lonely country road by an old car; the driver and passenger, an ageing man and woman who turn out to be brother and sister, gather up the young man’s body and drive it back to their farmhouse, nestled in a valley by railway tracks. The body is placed in a densely cluttered room which once belonged to the couple’s older brother. For the next fifty minutes, Scott cuts back and forth between the activities of these two strange siblings – the woman, Jessica (Rosamund Greenwood), who speaks in an endless, reminiscing monologue, and the man, Ambrose (Roy Evans), who never says a word as he goes about his work on the farm and tends a small lead mine over the hill.

We learn who these people are, their history and feelings, as the woman speaks to the dead young man whom she arranges in a chair, cleans and eventually dresses in the military uniform of the long-gone older brother James, who came back from Dunkirk wounded and never recovered. Gradually, the dead cyclist is transformed in Jessica’s mind into the lost brother and she grows to fear what Ambrose is planning – we see the taciturn farmer gathering scraps of wood which he gradually pieces together into a rough coffin. She even booby traps the room in an attempt to prevent Ambrose taking away her new companion who has filled a void which has existed since James’s death two decades before.

But eventually Ambrose carries the dead young man out to the yard, boxes him up, and wheels him on a barrow up the hill to a small copse where he’s dug a grave beside the one in which, years before, the brother and sister buried James. With this new, substitute brother now also in the ground, the two of them head back down the hill to the lonely farm

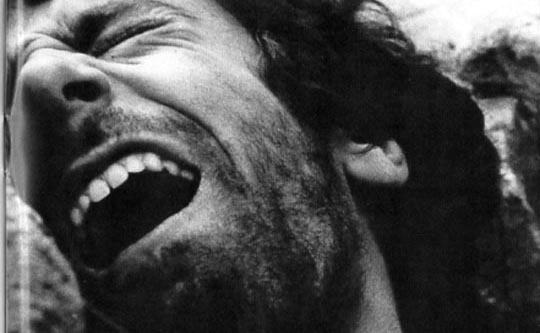

Scott establishes and maintains a distinctive tone in this film, steeped in loneliness, loss and longing, providing a rich setting for three remarkable performances. At first, it appears that Greenwood has the most difficult task – in a sense, she provides a non-stop stream of exposition; everything we know about these people and their history comes from what she says. But her performance only works within the context of Evans’s grim silence (she has an enormous emptiness to fill and he gives her no emotional assistance at all); but even more important is what David Pugh does as the dead cyclist. As the film progresses, the viewer can’t help but move from fascination to awe: Pugh is on-camera for long stretches of time, propped in that chair, eyes open and glazed with death, and while initially we might keep an eye on him to see if he moves, or blinks, or breathes, eventually we watch him because somehow his complete stillness takes on its own personality and he becomes a focus of almost unbearable emotional pain, a heavy physical presence asserting its own identity against the relentless onslaught of Jessica’s projection of another personality onto him.

I’ve never seen anything else quite like Loving Memory. One wonders what might have happened if the British film industry had been healthy enough to engage the talent which made it. But, after some festival success, the film was too strange and too awkward in length to gain any real distribution. Scott spent the next decade working with Ridley at their production company, making commercials, before he finally directed his first mainstream feature, The Hunger (1983). This, his first American movie, is saturated in artiness rather than art, all flashy surfaces reflecting those years of directing commercials. But I think, having seen Loving Memory and glimpsed the roots of Tony Scott’s filmmaking, I can understand better now what’s going on in so many of his movies, his background in painting and visual arts adding a surface gloss to the highly commercial projects he has focused on in his three decades of Hollywood thriller making.

Scott has never again made a film in England, and he has never again written his own scripts. I can’t help feeling that a genuine talent got diverted and, in some sense, has just made do with whatever has been offered to him by circumstance.

Comments

I guess I wasn’t watching or listening carefully enough. I thought Ambrose and Jessica were husband and wife, and that the dead cyclist had taken the place of their long-dead son for Jessica. Great movie, though.