Recent viewing: March-April 2018

I’d have to be writing for this blog every day to keep up with my compulsive viewing … something I simply don’t have the time for. But rather than let too many movies fall through the cracks, I’ll once again jot down a few brief notes about some of the disks I haven’t yet mentioned from the past month or so.

Animation:

It would be easy to get the impression, looking at the average multiplex marquee, that CG has all but obliterated all other forms of animation, yet dedicated animators do continue to painstakingly draw their films, or mold them out of plasticine.

Coco (Lee Unkrich & Adrian Molina, 2017)

As this Pixar feature began, I sensed that the groundbreaking company was becoming increasingly Disneyfied. The plucky hero, the market-tested ethnic angle, the overdetermined conflict between the hero and his restrictive family which you just know will be resolved by fade-out with everyone learning a valuable life lesson … and all of this is definitely there, but once Miguel crosses over into the Land of the Dead seeking some kind of validation for his musical ambitions, the film kicks into full inventive Pixar mode, with imaginative environments, colourful characters, plot twists and genuine (rather than Disney ersatz) emotion. (Disney Blu-ray/DVD. Extras: commentary, deleted scenes, multiple featurettes.)

The Red Turtle (Michael Dudok de Wit, 2016)

This Belgian feature, co-produced by Studio Ghibli, is exquisitely drawn, yet I found the narrative only vaguely engaging. A man shipwrecked on an island is repeatedly thwarted in his attempts to escape on handmade rafts by a giant red turtle, which smashes his vessels and drives him back to shore. This animal transforms into a woman who becomes his companion; they live together for years, have a child, grow old … the boy grows and swims away, the couple stay together until the man dies and the woman returns to the sea, once again a turtle. The story seems trite to me, but the images are often quite breathtaking. (Sony Pictures Blu-ray. Extras: commentary, three featurettes.)

The Girl Without Hands (Sébastien Laudenbach, 2016)

French animator Sébastien Laudenbach takes a very different visual approach; instead of Michael Dudok de Wit’s visual precision, Laudenbach uses little more than impressionistic brushstrokes to recount this Brothers Grimm story about a peasant’s daughter who is sold to the Devil in exchange for riches. However, her purity serves to prevent the Devil from claiming her, although he cuts her hands off in anger. She sets off on a journey of self-discovery, which leads her to a prince who falls in love with her; but the Devil sours their romance with lies. Although things are eventually resolved, there’s a lot of suffering along the way. Laudenbach actually animated the entire film himself, using a style which merely suggests images rather than rendering them clearly, giving it the feel of an old storybook come to life. (Shout Factory/GKids Blu-ray/DVD. Extras: making of, director interview, several short films by Laudenbach.)

The Pirates!: Band of Misfits (Peter Lord, 2012)

I somehow missed this Aardman feature when it was released, perhaps because Disney and Gore Verbinski had beaten the pirate genre into the ground with the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise. Although the script isn’t as richly packed with comic details as the studio’s best, it’s nonetheless entertaining, with some impressive large-scale sequences packed with crowds of characters. The story details the inept efforts of The Pirate Captain (voice of Hugh Grant) to claim the year’s award for best pirate, but the film’s greatest pleasures lie in the intricate stop-motion of the Aardman animators under Peter Lord’s direction. (Columbia Pictures Blu-ray/DVD. Extras: commentary, short films by Lord, featurettes, games.)

*

Musicals:

My taste in musicals tends towards Warner Brothers in the ’30s, with the kitsch excesses of Busby Berkeley, and the occasional production from later decades – particularly Singin’ In the Rain (Gene Kelley & Stanley Donen, 1952), and oddities like Patrick McGoohan’s Catch My Soul (1972) – but I have to be in a particular mood to sit through something by Rogers and Hammerstein or Lerner and Loewe. You couldn’t find two more radically different musicals than a pair I recently watched.

All That Jazz (Bob Fosse, 1979)

Bob Fosse, a renowned choreographer, made only five features in fourteen years, and only three of them were musicals. Although he started with a fairly traditional project, Sweet Charity (1969, based of Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria), beginning with his second feature, Cabaret (1972), he proved an innovative filmmaker who stretched the possibilities of the genre. That film also established showbiz as his big subject, the clash of reality and artifice and how that clash impacts identity. His two non-musical dramas, Lenny (1974) and Star 80 (1983), pursued the destructive forces of celebrity to relentlessly bleak conclusions, but his third musical – and most radical film – dug deeper, becoming one of the richest examinations of creativity, celebrity, and self-destructive obsession in cinema. When All That Jazz was released in 1979, it got a mixed reception, partly due to its extreme self-consciousness (it wears the influence of Fellini proudly on its sleeve) and partly due to what could be seen as an egotistical, self-aggrandizing self-portrait of Fosse as a genius artist.

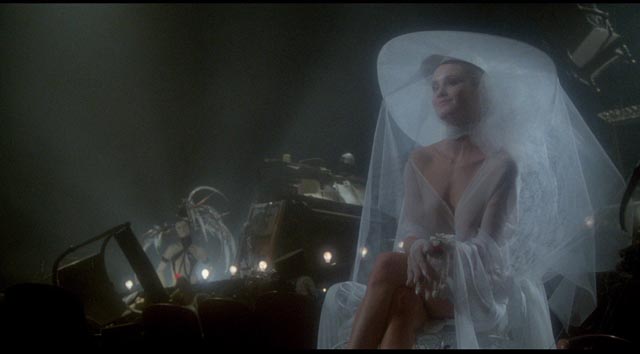

Roy Scheider plays choreographer Joe Gideon – he even looks like Fosse – an obsessive workaholic putting together a new Broadway show while simultaneously trying to finish a long overdue and over budget movie (a fictionalized version of Lenny). Smoking non-stop, popping uppers all the time, hitting on desperate young women who want a shot at a place in the chorus line, all while juggling a mistress and an ex-wife who happens to be starring in the show, not to mention trying to nurture his young daughter’s dancing ambitions, Joe is a monster whose charm for those around him lies in his enormous creative abilities. Watching the film now is perhaps more uncomfortable than it was when it first came out because he’s the kind of man who would now be exposed and condemned for his predatory sexual behaviour. But as his body begins to give out from the strain (he has a heart attack which puts the show in jeopardy), and he converses in some inner space with the beautiful figure of empathetic death (Jessica Lange), he does gain some self-awareness about the damage he has inflicted on the women in his life … all of this played out in a lengthy series of spectacular musical numbers.

Although Fosse’s self-portrait is problematic (he wrote the film with Robert Alan Aurthur after suffering a heart attack), the filmmaking is exhilarating and transcends the obvious elements of homage to Fellini; by the end, Joe Gideon embraces his own mortality, transforming death into a production number under his own control. There’s been a lot of debate recently about whether creative power negates bad real-life behaviour. All That Jazz doesn’t excuse Joe’s treatment of the women in his life, but while celebrating his creative achievements it does acknowledge the damage he has nonetheless caused – in other words, it reflects the complexity of this particular individual’s life and the impossibility of reducing human experience to clean and comfortable dimensions. (Criterion Collection Blu-ray/DVD. Extras: two commentaries, interviews and featurettes, documentaries on Fosse and the soundtrack.)

The Fantasticks (Michael Ritchie, 1995/2000)

It’s not always easy to comprehend Hollywood career trajectories. Michael Ritchie, who got his start on television in the 1960s, scored critical and popular successes with a handful of features beginning with Downhill Racer in 1969. His work was both technically polished and stylistically innovative, although it gradually became more conventional through Prime Cut (1972), The Candidate (also 1972), Smile (1975), The Bad News Bears (1976) and Semi-Tough (1977) … but from An Almost Perfect Affair (1979) on he slipped into a mediocrity which he seemed unable to escape for the rest of his career.

Then towards the end, he invested himself in what was obviously a real labour of love: a film version of Off-Broadway’s longest-running musical, The Fantasticks by Tom Jones and Harvey Schmidt. It was a risky choice, a small, insubstantial musical at a time when traditional musicals were essentially non-existent on-screen. Ritchie made the film in 1995, but it was five years before it was released in a severely cut-down form (courtesy of Francis Ford Coppola). Given the slightness of the project, stripping out several major musical numbers didn’t really help, and the film disappeared. Ritchie died the following year.

The Fantasticks is a self-conscious attempt to recapture a mythical time and place, a gentle rural middle America populated by decent people who live close to the land and hold close to old-fashioned family values. Neighbours Amos Bellamy (Joel Grey) and Ben Hucklebee (Brad Sullivan) want their kids to fall in love and marry, so they fake a bitter family feud to inspire a star-crossed, Romeo-and-Juliet bond between Luisa (Jean Louisa Kelly) and Matt (Joey McIntyre). With the bond forged, the time has come to resolve the feud and pave the way for union; enter a travelling fair headed by El Gallo (Jonathan Morris) who seems to have magical powers. (Echoes of Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes and Charles G. Finney’s The Circus of Dr. Lao, but with the darker edges shaved off.)

There are complications and misunderstandings and disillusion before the two kids come to realize that home is best and family is all that matters. The film is visually quite lovely (evoking the open expanses and just-plain-folks of Rogers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma) and most of the cast have an easy-going charm … but it’s hard to sustain something this gossamer-thin on film without seeming cloying and slipping into sentimentality. It doesn’t help that most of the numbers are as languid as the long summer day over which the action plays out. As pretty as the film is, its deliberately unhurried pace becomes soporific, sapping the bittersweet ending of any real emotional strength.

The best thing about the Twilight Time Blu-ray is the inclusion of both versions of the film – the eventual theatrical release in hi-def, the original cut in standard definition (which looks almost as good as the shorter cut). Not surprisingly, with almost twenty-five minutes trimmed by Coppola, the theatrical version seems even less substantial; as languorous as Ritchie’s cut is, the narrative makes more sense in his version. Particular damage was inflicted by the deletion of the first musical number, which plays over the long title sequence as the fair arrives in the community; the show’s biggest hit, “Try to Remember”, sung by El Gallo, sets the tone and establishes the idea of the wistful dreams which drive the characters. By losing this and beginning immediately with a scene of the feuding parents and the kids trying to slip away to be together, the shorter version raises expectations that the story will have more substance than it actually does. (Twilight Time Blu-ray. Extras: three commentaries, two versions of the film.)

*

Twilight Time:

And speaking of Twilight Time, I’ve been trying to catch up on my small stockpile of their releases. In addition to The Fantasticks, I’ve recently watched four more (with seven left to go, and an additional five new releases on the way!).

The Glory Guys (Arnold Laven, 1965)

Director and co-producer Arnold Laven had a long television career spanning from the early ’50s to the mid-’80s, interrupted by an occasional theatrical feature. Most of these were B-movies, including noir, war and monsters (1957’s The Monster That Challenged the World), but his final four features were all westerns. What makes the biggest of these interesting is the fact that it was written by none other than Sam Peckinpah. Despite rumours that he directed it, Peckinpah was otherwise occupied during the 1965 production – getting fired from post-production on Major Dundee and pre-production on The Cincinnati Kid (eventually directed by Norman Jewison).

The Glory Guys (1965) has the earmarks of a Peckinpah project – a revisionist attitude towards western myth, an awareness of the violence propping up the myth, conflict and bonding within a male society (here the U.S. Cavalry). A fictionalized version of the Custer story, the film focuses on two friendly rivals, Captain Demas Howard (Tom Tryon) and scout Sol Rogers (Harve Presnell), who are both involved with widow Lou Woddard (Senta Berger, who had just appeared in Major Dundee) while simultaneously getting caught up in a campaign against the Sioux. Their biggest problem is that their commanding officer is the megalomaniac General Frederick McCabe (Andrew Duggan). On a previous campaign, Howard had seen McCabe sacrifice a large number of men in a poorly planned battle and he fears that the same is about to happen again.

He’s not wrong. Assigned to whip a ragged group of raw recruits into a coherent unit in very little time, Howard has been targeted by McCabe to lead these inexperienced men into a trap to draw out the Sioux so he can massacre the tribe (against express orders from his own commanding officer). Howard does what he can to save his men, managing to keep some of them alive, only to discover that McCabe’s larger force was itself lured into a trap and wiped out by the superior strategy of the Sioux.

There are echoes here of John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948), but rather than a young officer’s inexperience precipitating disaster, it’s the callous disregard of a senior officer for the lives of his men which results in catastrophic defeat. Peckinpah’s contempt for the arrogance of authority permeates the film, making the cliched three-way romance seem even more trivial. Laven directs efficiently, handling the logistics of the large-scale action scenes with skill, and the film seems like yet one more bridge between the traditional western and the revisionism which exploded the genre when Peckinpah finally got his big chance with The Wild Bunch four years later. (Twilight Time Blu-ray. Extras: commentary, documentaries on Peckinpah and cinematographer James Wong Howe, promotional gallery.)

Pretty Poison (Noel Black, 1968)

Noel Black was another director whose career was mostly in television, interrupted intermittently with a handful of forgettable features. Which makes it that much stranger that his first feature (after a couple of shorts) is a terrific piece of work which plays with genre and tone in interesting ways and draws from its two stars some of the best work of their careers.

Pretty Poison (1968), adapted by Lorenzo Semple Jr. from a novel by Stephen Geller (himself an occasional screenwriter), has a light and breezy surface which conceals a very dark heart. It opens with Dennis Pitt (Anthony Perkins) being released from a state institution where he’s been held since his teens, when he burned down a house and incidentally killed his aunt. Dennis’ big problem is that he’s an obsessive fantasist, constantly embellishing his identity with fictions to make himself seem more interesting and his life more exciting. Warned to keep this in check by parole officer Morton Azenauer (John Randolph), Dennis immediately breaks parole and disappears into a small Massachusetts town where he gets a job at a chemical plant.

While pretending to be an agent planted at the company to spy on saboteurs who plan to poison the region, Dennis is attracted to a perky high school cheerleader. Sue Ann Stepanek (Tuesday Weld) is a dream girl, a perfect character for Dennis’ fantasy, and he draws her in with cryptic remarks until she becomes his “civilian” helper. Trouble is, as it turns out, Sue Ann is a sociopath who takes that fantasy and runs with it, manipulating the weak and naive Dennis into helping her get rid of her controlling mother.

Black and Semple cannily play with Perkins’ established image as Norman Bates and Weld’s iconic appearance as the perfect All-American smalltown girl to create an atmosphere of feverish paranoia in a kind of proto-Blue Velvet. The moment halfway through when Sue Ann turns Dennis’ fantasy into grim reality still has the power to shock; Weld plays the scene with a cheerful lack of affect which amplifies Perkins’ desperate helplessness, and his increasingly ineffectual attempts to retain control of his fantasy pull the film into a darker place which casts a retrospective shadow over the seemingly lighter, more comedic first half. It’s a puzzle why Noel Black was never able to follow Pretty Poison with anything as distinctive in a career which continued for more than two decades. (Twilight Time Blu-ray. Extras: two commentaries, deleted scene featurette.)

The Yellow Handkerchief (Yoji Yamada, 1977)

In contrast, Japanese master Yôji Yamada has sustained a career of nearly sixty years with almost ninety features to his credit, the latest due for release this year at the age of eighty-six – a career marked by commercial and critical success, from his long-running Tora-san series to his Twilight Samurai trilogy. Yamada is a subtle and sensitive observer of Japanese social conventions who imbues his films with deep emotional resonance, and much of his work can hold its own in the company of Ozu, Naruse and Mizoguchi.

The Yellow Handkerchief (1977) is a road movie set in northern Japan, on the island of Hokkaido (as was another of his gentle masterpieces, A Distant Cry From Spring [1980]). Based, surprisingly, on a story by New Yorker Pete Hammill, the film introduces three disparate characters who come together by chance and gradually exert an influence over each other’s lives. Kin’ya (Tetsuya Takeda) is a boorish young man who runs away from a romantic disappointment by driving north in his small car. Fresh off the ferry, he hits on a shy young woman, Akemi (Kaori Momoi), who is running from her own unhappiness. He offers her a ride, but solely in hope of getting her to bed. This plan is sidetracked when they encounter an older man, Yûsaku (Ken Takakura), whom Akemi insists on giving a ride – partly out of generosity, partly no doubt to provide a buffer against Kin’ya’s intentions.

They wander Hokkaido’s country roads somewhat aimlessly, gradually learning about each other’s past and revealing their various degrees of emotional damage. When it’s revealed that Yûsaku has recently been released from prison after killing a man in a drunken brawl, the other two are drawn into his story – he left a wife behind and no longer knows what her circumstances and feelings are. Before leaving prison he wrote to her to ask that, if she still has feelings for him, she tie a yellow ribbon around a pole in front of their old house. But he’s afraid to go there in case there’s no sign, fearing rejection. Akemi takes charge and pushes them on towards the town where he once lived, her efforts to heal this damaged man’s spirit also having a maturing influence on Kin’ya. As in much of Yamada’s work, the narrative moves gently towards an emotionally resonant conclusion which gives a sense of depth to ordinary lives. (Twilight Time Blu-ray. No extras.)

American Buffalo (Michael Corrente, 1996)

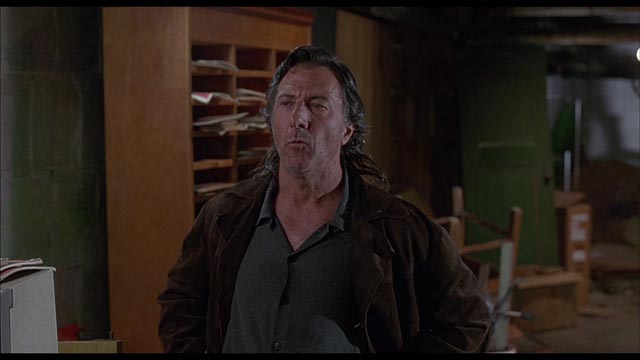

I have to be in the right mood for David Mamet. His hyperrealism can too easily seem overwrought and inadvertently comedic (though he does inject a lot of genuine comedy into much of his work). His characters can seem like hardboiled caricatures … but in the right mood, all this intensity is very entertaining. This proved true when I watched Twilight Time’s Blu-ray of American Buffalo (1996), a play from very early in Mamet’s career (1975) turned into a fast and engaging movie by Michael Corrente. This is the only thing I’ve seen directed by Corrente, and it’s a very assured piece of work, exemplary in its approach to a stage play which is cinematic without artificially “opening it up”.

Set in Chicago but shot in a run-down neighbourhood in Providence, Rhode Island, it all takes place in a cluttered junk shop and the street out front. Don (Dennis Franz) owns the store and mostly he just hangs out shooting the breeze with his buddy Teach (Dustin Hoffman), a guy with serious anger management issues. Don is pissed off because a few days ago a customer “took advantage” of him by buying what turned out to be a valuable coin for far less than it was worth. So now he plans to break into the customer’s place and steal it back, along with what he assumes will be a valuable coin collection. He has had his young Black protege Bob (Sean Nelson) watching the guy.

When Teach gets wind of the plan, he starts driving a wedge between Don and Bob, trying to cut the kid out of the plan and take advantage of the opportunity himself. Teach is a manipulative sociopath, a sweaty, greasy monster with the power to wreck everyone around him, all the while convinced of his own righteousness. As these characters bicker and argue, Teach works himself up to a casually brutal act of violence which is shocking in its unexpected inevitability.

Corrente uses the confines of the set and its surroundings as a dramatic pressure cooker; there seems to be no way these three men can escape the cramped boundaries of their pointless lives. He uses dynamic blocking to keep things restlessly moving until you feel that Teach is a predator relentlessly pursuing his prey, who just as compulsively tries to keep ahead of him, looking for breathing space in the nooks and crannies of the store. Corrente is aided by excellent production design from Daniel Talpers, moody cinematography by Richard Crudo and superb editing by Kate Sanford which, while never feeling forced, never allows the tension to ease.

But inevitably for a Mamet piece, it’s ultimately the actors who invest the script with life; Franz and Hoffman have never been better, every glance, every gesture no matter how small and fleeting, has dramatic force, while 16-year-old Nelson (two years after his debut starring in Boaz Yakin’s Fresh [1994]) remarkably holds his own against the old pros, becoming the empathetic centre of the film. A young guy with ambitions to make something of himself as a petty criminal, he looks up to Don and Teach only to be abused and betrayed by them. It’s his presence that makes the film more than an exciting display of acting virtuosity. (Twilight Time Blu-ray. Extra: commentary.)

Comments