Murder, demons, superheroes and martial arts: recent viewing

Vinegar Syndrome

Last year I grew increasingly frustrated with my Vinegar Syndrome subscription as the ratio of desirable new releases to what was, for me at least, junk tipped over so far that I couldn’t justify the expense. With each new announcement this year I’ve felt relieved that I wouldn’t be receiving a lot of stuff I have no interest in. While I do still occasionally order something, it’s a lot easier to resist now. In fact, so far this year I’ve only bought a couple of new releases, both 4K upgrades of movies I already had (I know, I’ve been trying to avoid that trap, but it’s hard).

Murderock (Lucio Fulci, 1984)

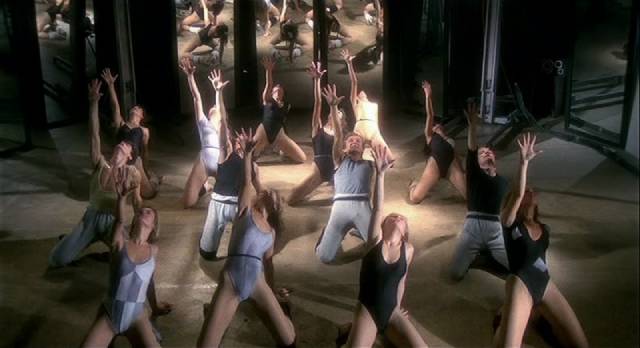

What tempted me to re-buy Lucio Fulci’s Murderock (aka Murder-Rock: Dancing Death, 1984)? His last fling at the classic giallo, it shows him pulling back decisively from the genuinely disturbing excesses of The New York Ripper (1982), its violence toned down in favour of the soft-core excesses of Flashdance (1983). Though comparatively tame, it nonetheless goes through the genre motions effectively and the 4K upgrade serves the ’80s sleaze well. The disk comes with a commentary and almost four-hours of new and archival interview featurettes.

Who Killed Teddy Bear? (Joseph Cates, 1965)

Sleaze of a different kind permeates the much more interesting Who Killed Teddy Bear? (1965), the second of only three theatrical features by television producer-director Joseph Cates. More surprising than the twisted psycho-sexual aspects of the script by Leon Tokatyan and Arnold Drake are the cast members who were willing to commit to the unsavoury material, beginning with Sal Mineo, who pretty much ended his theatrical career with his portrayal here of a sweaty pervert who becomes obsessed with and stalks a co-worker at a low-rent New York night club. That co-worker is played by dancer Juliet Prowse, while their boss is none other than Broadway star Elaine Stritch, who also hits on Prowse with undisguised lesbian intentions. Showing up in smaller roles are Daniel J. Travanti (destined for TV stardom on Hill Street Blues [1981-87]), and familiar character actors Frank Campanella and Bruce Glover. Seeing this relatively prominent cast in what amounts to a B-movie roughie is disorienting, making you look for something more substantial in the story than what’s actually there. It’s a fascinating artifact from a time when Hollywood was pushing against the crumbling walls of the Production Code, enhanced by the atmospheric location photography by Joseph Brun. Released in a dual-format edition by Vinegar Syndrome sub-label Cinematographe, the film is given an excellent transfer and comes with a commentary and three featurettes – an interview with Strand Releasing founder Mike Thomas, who helped save the film from oblivion, a locations survey by Michael Gingold, and a video essay by Chris O’Neill.

I also watched a couple of disks from my VS backlog.

Beyond the Door III (Jeff Kwitny, 1989)

I’m a sucker for movies set on trains and I love horror movies, so what could be better than a horror movie set on a train? The second of only three features made by Jeff Kwitny, who went on to a brief career writing episodes for various animated series in the ’90s, Beyond the Door III (1989) is a movie unafraid of its own silliness, giving rise to some entertainingly jaw-dropping moments once it boards a possessed train in Serbia. But it begins with a group of American college students who go on a field trip to study folklore in the Balkans under the guidance of Professor Andromolek (Bo Svenson), who takes a particular interest in Beverly (Mary Kohnert), an asocial outsider exploring her family’s roots in the old country. Weird things start happening immediately, beginning with her mother’s death in a crash just after the plane leaves. Once the group reach a remote village, the sinister locals start killing them off; the survivors run for their lives, eventually hopping on that train … but there’s no safety. The train takes on a malevolent life of its own, jumping the tracks, plowing through a swamp, changing direction, and killing more of the students before carrying Beverly back for a ceremony in which she’s to be wed to the Devil. Nicely shot in widescreen on some interesting locations by Italian cinematographer Adolfo Bartoli, the movie manages to overcome some weak acting and builds considerable atmosphere. VS’s dual-format edition presents an excellent image along with interviews with Kwitny, Svenson and Bartoli.

Mark of the Devil (Michael Armstrong, 1970)

I received VS’s 4K upgrade of Michael Armstrong’s Mark of the Devil (1970) a couple of years ago as part of my subscription, although I already had Arrow’s perfectly fine Blu-ray edition. VS have included most of the extras from that edition, adding a few more, so the real value here is the improved image quality. The film itself still stands as a potent treatment of the European persecution of “witches” by civil and Church authorities, with a greater (more exploitative?) emphasis on the psycho-sexual pathology of those authorities. Michael Reeves’ Witchfinder General (1968) and Piers Haggard’s Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971) seem tasteful and somewhat tame in comparison, but it’s Armstrong’s movie which captures the sense of historical madness most powerfully, bolstered by an excellent cast. Herbert Lom’s perverted inquisitor is more convincingly unwholesome than Vincent Price in Reeves’ movie, while Udo Kier, near the beginning of his long career, plays an innocent who gradually discovers that the man he reveres is a monster; it was only three years later that Kier unleashed a knowingly comic sense of moral corruption in Paul Morrissey’s Flesh for Frankenstein (1973) and Blood for Dracula (1974). Reggie Nalder, an unsettling character actor who had first made his mark in Hollywood in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), is a stand-out as Albino, a petty official who uses the witch hysteria to prey on women who spurn him.

*

88Films

88Films in the U.K. specialize in Italian and Asian genre releases and my recent acquisitions have been Chinese and Japanese titles.

Zebraman/Zebraman 2: Attack on Zebra City (Takashi Miike, 2004/2010)

The extremely prolific Takashi Miike honed his craft in the realm of V-Cinema, with a couple of dozen violent crime movies in the ’90s, gradually branching out into theatrical films in the same genre – the Black Society Trilogy, the Dead or Alive trilogy, and others – before finding international success with the psychological horror of Audition (1999). But much of his work remained too extreme for a broader audience – the double-dose of Visitor Q and Ichi the Killer in 2001 was particularly potent. I’m not sure which of his movies I saw first, but while Audition left its mark, it was Bird People in China (1998) which made me a fan – this mix of yakuza noir and fantasy was quite unlike anything else I’d seen and despite the range of Miike’s subsequent work, it’s that strain of fantasy which continues to appeal to me; this shows up in works as dark as the television series MPD Psycho (2000) and the myth-infused yakuza drama of Gozu (2003), but also in some strange “family-oriented” movies like The Great Yokai War (2005), which are very disorienting to Western eyes not used to such disturbing imagery in what on the surface appears to be a kids’ movie.

In this vein, Miike made a pair of superhero movies about a character based on an old, unsuccessful TV show seemingly remembered only by a young handicapped boy and his sad teacher. Shô Aikawa, better known for his cool crime movie persona, is quite touching as Shin’ichi, held in contempt by his own family while he secretly sews himself a replica of the Zebraman costume which he wears in the privacy of his study. In Zebraman (2004), a crime wave is washing over his Yokohama neighbourhood (rape and murder are pretty dark for a family movie) and Shin’ichi begins to sneak out at night in first tentative steps to act out his heroic fantasy. He eventually discovers what the authorities already seem to know – that glutinous aliens have landed and taken up residence beneath the school, spreading out to take possession of the area’s residents and triggering all the antisocial behaviour.

Confronting the threat, Shin’ichi discovers himself to be taking on the powers of Zebraman, becoming a media celebrity and eventually facing off against the giant alien blob-creature at the school. Seven years and twenty-one credits later, Miike made a sequel, Zebraman: Attack on Zebra City (2010), which goes in a very different direction. It’s fifteen years later and Shin’ichi wakes from a coma with amnesia to find that what’s now called Zebra City exists as a police state under Mayor Aihara (Guadalcanal Taka), who somehow split the teacher/superhero into two parts – the good Zebraman and the evil Zebra Queen (Riisa Naka), whose pop music celebrity distracts the population from the Mayor’s plans. Every day for five minutes, there’s Zebra Time, essentially a mini-Purge during which anything goes while the police are free to kill anyone they run into. In this nightmare dystopia, Shin’ichi has to find himself again and overthrow the forces of oppression. Darker and more perverse than the first film, the sequel sees Miike’s imagination running wild. Though his inventions aren’t always successful, the imagery is striking and he obviously has a knack with the music-video numbers performed by Zebra Queen.

Both films get an excellent presentation on 88Films’ Blu-rays, which each include a commentary and multiple featurettes.

In the Line of Duty I-IV (Various, 1985-89)

Although packaged as a set, the four movies included in 88Films’ In the Line of Duty box aren’t really connected, other than in having female leads skilled in martial arts. They’re even labelled out of chronological order for some reason. The first film (number 2 in the set), Corey Yuen’s Yes, Madam! (1985), is significant not only for having given Michelle Yeoh her first big starring role as Inspector Ng of the Hong Kong police, but also for being the first appearance on screen of Cynthia Rothrock, who despite being given lower billing is Yeoh’s co-star as British Inspector Carrie Morris. Actresses in HK action films at the time were more often used as comedy relief, but here these two highly competitive cops get some spectacular opportunities to kick ass as they team up to bring down a criminal organization which murdered a British cop.

Yeoh returned to star in David Chung’s Royal Warriors (1986) – labelled number 1 in the set – renamed CID officer Michelle Yip, who teams up with a Japanese Interpol agent (Hiroyuki Sanada) and a security guard (Michael Wong) when the three thwart an attempted airliner hijacking. The terrorist militia responsible target the trio while also carrying out a series of attacks in Hong Kong. In Brandy Yuen and Arthur Wong’s In the Line of Duty III (1988), Cynthia Khan takes over the lead as Rachel Yeung, a rookie determined to prove herself (and played more comedically than Yeoh’s higher-ranking officers) when a pair of violent Japanese jewel thieves arrive in Hong Kong with a Japanese cop (Hiroshi Fujioka) on their trail determined to get revenge for the murder of his partner. Khan stars again in Yuen Woo-Ping’s In the Line of Duty IV (1989), joined by an American cop (Donnie Yen) on the trail of drug traffickers. It turns out that the syndicate has people inside the HK police force and the pair find themselves being pursued by corrupt cops as well as killer criminals.

Like so many Hong Kong action movies, these four are tonally variable, mixing violence with slapstick, both breaking and confirming gender stereotypes. What isn’t in doubt is the skill of the leads as they engage in big, elaborate fight sequences which look dangerous and painful, but provide the undeniably exciting spectacle Hong Kong cinema has long been famous for. Although not entirely consistent, the transfers are generally fine, with two of the films included in their original and export versions, with multiple language choices, new and archival commentaries and featurettes.

The Project A Collection (Jackie Chan, 1983/1987)

After almost a decade of bit parts and an attempt to mould him into a successor to Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan began to hit his stride when Yuen Woo-Ping recognized his comedic abilities and gave him the starring role in Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow (1978). He rose rapidly over the next five years, gaining international recognition and beginning to write and direct his own projects, showing that he understood his particular talents better than anyone else. Then, with his fourth film as writer-director-star, he transformed Hong Kong action cinema. A big, ambitious historical spectacle, Project A (1983) paved the way for such movies as Sammo Hung’s Millionaires’ Express (1986) and Tsui Hark’s Once Upon a Time in China series (1991-94) which invested elements of Chinese history with a rousing sense of adventure.

At the turn of the 20th Century, Hong Kong is plagued by pirates and efforts to deal with the problem are complicated by rivalry between the police and the Coast Guard. Chan plays Dragon Ma, a sailor in the Coast Guard whose irreverent attitude constantly gets him in trouble. With supporting roles for Sammo Hung and Yuen Biao, the movie stands as a defining work for Chan’s style of filmmaking, rooted in the athletic, comedy-laced traditions of the Peking Opera where he and his friends had trained since childhood. While the comedy is sometimes broad, the plentiful action is imaginatively choreographed.

After diversions into the present with Police Story (1985) and Operation Condor 2 (1986), the movie that almost killed him, Chan conjured up a sequel whose rather unimaginative title, Project A Part II (1987), belies another rousing comedy-adventure, this time with Ma transferred to the police force and assigned to an area where a corrupt officer essentially runs all criminal activity, boosting his reputation by staging ostentatious arrests of his criminal associates. Ma has his work cut out to expose Superintendent Chun (David Lam); things are complicated by a group of revolutionaries and several implacable agents of the Empress Dowager who are tracking them. Once again, the fights are spectacular and, while Sammo Hung and Yuen Biao aren’t here, both Rosamund Kwan and Maggie Cheung appear as revolutionaries.

Chan’s two epics were high-points of ’80s Hong Kong cinema and 88Films give them excellent presentations in 4K transfers from the original negatives, each in two versions – the original HK cuts, plus the longer Taiwanese cut of Project A and the shorter export cut of the sequel. There are commentaries, interviews and making-ofs for both films.

Comments