Chinese action and fantasy from Eureka

As I recently mentioned, Eureka has been releasing a lot of Asian movies and I’ve binged quite a few, including the Once Upon a Time in China Trilogy and a number of Sammo Hung titles.

As an indication of the looseness of franchises, Eureka’s edition of Tsui Hark’s films about the legendary Wong Fei-hong consists of four movies despite the Trilogy title of the set. Once Upon a Time in China 1-3 are supplemented with Sammo Hung’s Once Upon a Time in China and America (which is actually the sixth film in the series). Tsui Hark has had a remarkably prolific career as producer, writer and director since he began making movies with The Butterfly Murders in 1979. I saw that and his controversial third feature Dangerous Encounter First Kind (aka Don’t Play with Fire, 1980) when I was living in Hong Kong for a while in 1980-81 and the latter in particular had a huge impact on me. Despite having been forced to reshoot and re-edit the film by the censors, it was really disturbing and intensely visceral.

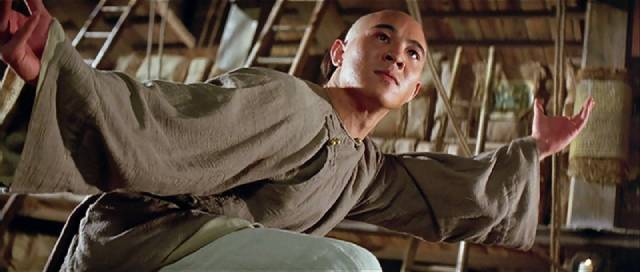

Although his work has ranged over a number of genres, Tsui has made and produced a great many martial arts movies, some historically based, others leaning heavily on fantasy, since Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain (1983), but the Once Upon a Time trilogy (1991-92) is something of a peak, epic in scale, with hugely elaborate action sequences which feature dozens if not hundreds of stunt performers engaged in fights with multiple points of focus. Just on a logistical level, they are awe-inspiring, but they’re also well-constructed narratives revolving around the social and political conflicts which arose from the presence of Western colonial powers in China in the 19th Century. Wong (Jet Li) keeps finding himself drawn into those conflicts and forced to fight for the rights of the Chinese which are continually being trampled by arrogant Brits and Americans.

Chinese honour not only runs headlong into Western duplicity; it also has to overcome betrayal by conflicting Chinese factions which work against self-determination because there are rewards to be had by aligning with the colonial powers. The opium trade and selling women into sexual slavery play a part, as well as tricking workers into indentured servitude overseas. Wong, a real figure who became a folk hero, uses his martial arts skills to protect the exploited and (at least temporarily) defeat smug Europeans and Americans who always make the critical mistake of underestimating the Chinese.

As in many Chinese movies, the drama is laced with some broad comedy, but this doesn’t undermine the overall impact of these colourful and exciting action films. Sammo Hung’s Once Upon a Time in China and America (1997) leans harder on comedy by transporting Wong Fei-hong to 19th America to visit a former student who has established a Chinese pharmacy in a small western town. The strange behaviour of this land’s inhabitants and Wong and his companions’ unfamiliarity with foreign customs make for easy fish-out-of-water humour – but it gets awkward with the film’s depiction of Native Americans, who are first introduced in a small massacre and then appear as a synthetic theme park representation based on old movies.

The film deals with racism towards Chinese immigrants in the town, but seems oblivious of the historical condition of the Native Americans displaced by European expansion. Perhaps it’s too much to expect an action comedy to address these darker issues, but the blind spot leaves a slightly sour taste. However, Hung handles the action well, though the movie is mounted on a more modest scale than Tsui’s trilogy.

Tsui was a key figure in the revitalization and transformation of the martial arts genre into what we’re now familiar with – movies like those of Zhang Yimou (Hero, House of Flying Daggers, Shadow), Ang Lee (Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon) and late John Woo (Red Cliff). The first two movies in Eureka’s Three Films with Sammo Hung set belong to an earlier stage, the proliferation of movies produced by the Shaw Brothers and others from the mid-’60s into the ’80s, the rules of which were established by King Hu and his contemporaries with films like Come Drink With Me and Dragon Gate Inn, which combined spectacular fight choreography with stories of imperial political intrigue and ubiquitous rivalries among various martial arts schools.

Both The Iron-Fisted Monk (1977) and The Magnificent Butcher (1979) reflect one of the oddities of Hong Kong cinema which may be disconcerting to a Western viewer, a mixture of clashing tones which juxtapose slapstick comedy with shocking brutality. In both films, villainous characters played by Fung Hark-on brutally rape and murder young women, while fights are choreographed for a mixture of comic detail and bone-crushing violence. This kind of tonal discord is one of the distinguishing characteristics of the genre, generating a sense of excitement with an undertone of discomfort; these movies are often extremely formulaic, and yet this quality adds a sense of uncertainty about what the viewer will experience. How should one react when Sammo plays for comedy a scene in which he slips into bed with the woman he’s attracted to, not realizing that she’s dead because the villain got there before him?

In The Iron-Fisted Monk, Hung’s directorial debut, he plays Husker, a man who works at his uncle’s food stall. When a brutal Manchu official (Fung) beats his uncle to death, Husker is saved by the titular monk and sent to the Shaolin Monastery to train in the martial arts. Too impatient to complete his training, he runs away, determined to get revenge on the Manchus. When he gets into a fight protecting some children who are being tormented by several Manchu men, another man rushes in and stabs one of them to death. Liang (Lo Hoi-pang), a worker whose sister committed suicide after being raped by the Manchu official, wants revenge even more than Husker. Unfortunately for the latter, everyone thinks he killed the man.

From that point, the narrative focuses on the dye factory where Liang works, which corrupt Manchu officials are determined to steal from the Chinese owner. Husker sets out to train the workers in martial arts so they can defend the factory, and he foils the Manchu scheme to take possession by bankrupting the owner. But that just brings down the wrath of the Manchus and, in a turn not likely to be seen in any equivalent Western action movie, the workers and owner of the factory are all massacred, including Liang. Only Husker and the Iron-Fisted Monk are left to exact revenge. Like many of these movies, a fairly simple story takes on unexpected emotional weight by playing by rules which would barely be acceptable in most Western commercial movies. (Kids in jeopardy, brutalized and killed, is another trope of Hong Kong movies which Western filmmakers would generally avoid.)

The Magnificent Butcher, directed by Yuen Woo-ping, runs along similar lines. Here Hung is Lam Sai-wing, a butcher in the local market who is also an impetuous student of Wong Fei-hung (Kwan Tak-hin). Sai-wing’s long-lost brother Lam Sai-kwong (Chiang Kam) arrives in town looking for his brother, with only a ten-year old photograph to identify him. Ko Tai-hoi (Fung again), the arrogant son of Master Ko (Lee Hoi-sang), who is a rival of Wong Fei-hung, sees Sai-kwong’s wife Yuet-mei (Tong Ching) and decides he has to have her. Trying to rescue his wife, Sai-kwong gets into a street fight with Ko and Sai-wing happens by and intervenes on Ko’s behalf. This begins a cascading series of misunderstandings which involve the two brothers, who don’t recognize each other, Ko and Beggar So, the Drunken Master (Fan Mei Sheng), Yuet-mei and Ko’s adopted sister Lan-hsing (JoJo Chan).

Superficially a comedy of mistaken identities, the film also features brutal rapes, murders and attempted suicides. Undeniably, the vicious behaviour of Ko Tai-hoi builds up an emotional desire for retribution, which is delivered in a brutal fight between Sai-wing and Ko. There’s a coda in which Master Ko seeks revenge on Sai-wing for the death of his son … and yet it still manages to end on a joke when Wong Fei-hung returns from a trip and chastises Sai-wing for a minor infraction, unaware of all the carnage which has occurred while he was away.

Both films are fine examples of the genre, with dynamic fights and those tonal shifts to keep viewers alert. The third film in the set is something completely different (and less satisfying, for me at least). Eastern Condors (1987), again directed by Hung, is a post-Vietnam action movie which mixes together elements of Rambo, The Dirty Dozen and The Deer Hunter. Years after the war, the Americans are concerned that the Vietnamese military is going to get its hands on a huge weapons stash which was left behind in an underground bunker. A group of Chinese-Vietnamese convicts are recruited to go on a mission, not officially sanctioned, to destroy the weapons.

They parachute into Vietnam and are met by some Cambodian guerrillas who serve as guides. There are skirmishes along the way; some of the men, who have not been fully briefed on the purpose of the mission, refuse to continue; someone turns out to be an enemy agent; and the Cambodians have no intention of destroying the weapons, wanting instead to appropriate them for their own cause. There’s the obligatory imprisonment in water cages and gambling with Russian roulette, betrayals and infighting, and a big showdown in the bunker between the team and the Vietnamese army commanded by an effetely snickering caricature (Yuen Wah).

Although there are martial arts fights scattered through the movie, it inevitably has more gunfights, which are inherently less interesting, as are the war movie cliches which prevent the characters from being as colourful as those in the period films. Given the history of the war, with China being the chief ally of Vietnam, it’s also a bit disconcerting that the story sides with the U.S. rather than the Vietnamese.

In addition to the three-disk set, Eureka has also released the nonsensically titled Wheels on Meals (1984), an action comedy directed by Sammo Hung, which reunites him with Jackie Chan and Yuen Biao, with whom he had trained in childhood at the China Drama Academy. The movie plays like three friends getting together for a goof, mixing elaborate stunts and fights with slapstick comedy inexplicably set in Barcelona. Chan and Yuen are Thomas and David, roommates who make a living with a food truck which they park in the city’s main square, while Hung is Moby, a wannabe detective who ends up with a case because his boss disappears to get away from some some shady characters he owes money to.

The case involves tracking down a young woman named Sylvia (Lola Forner), who turns out to be a pickpocket with whom Thomas and David get mixed up when they protect her from some men, not realizing that she’s just robbed them. The convoluted case revolves around Sylvia’s identity and an inheritance, which connects with David’s father (Paul Chang Chung), who lives in a mental hospital where he’s romantically involved with a fellow patient, who happens to be Sylvia’s mother, who once had an affair with a nobleman whose estate will go to Sylvia if she claims it within a very close deadline.

There’s a lot of running around and clashes with a gang of bad guys who work for the man who will inherit if Sylvia fails to make her claim, but the plot is beside the point – the stunts and fights are the reason the movie exists and once again a contemporary setting makes things less interesting. While in period martial arts films the action is often allowed to play out in wider shots so that the audience can appreciate the skill of the performers, in more contemporary settings there seems to be a tendency to construct the action more through editing, chopping it into smaller details which paradoxically make it less interesting as it speeds things up. And on top of that, the comedy is often pretty juvenile. It’s no doubt a matter of personal taste, but I much prefer the three stars’ period films.

*

A year after directing Wheels on Meals, Sammo Hung helped to launch a new strain of horror-comedies by producing Ricky Lau’s Mr. Vampire (1985). While the comedy tends towards slapstick again, it’s nicely balanced with the eerie atmosphere and occasional genuinely creepy touches of horror. For a Western viewer, the Chinese concept of a vampire seems fresh and original, a malevolent spirit somewhat constrained by the limitations of a dead body; these vampires hop stiffly rather than walk or fly, providing an image at once funny and disturbing.

When Taoist priest Master Kau (Lam Ching-ying) is asked by a businessman to dig up and rebury his father in hopes of bringing better luck to his family, the priest discovers that the body has not decayed at all. Suspecting that it is a vampire, he takes it back to his home to investigate. Using enchanted ink, a web of lines are drawn around the coffin to bind the corpse inside, but the underside is left clear and the dead man bursts free, creating havoc for Master Kau’s inept disciples Man-choi (Ricky Hui) and Chau-sang (Chin Siu-ho). Various complications ensue; the vampire escapes and kills his businessman son; Master Kau is arrested for murder; Man-choi is infected by the vampire; Chai-sang is seduced by a female ghost; and there are bouts of mystical combat between the Master and his disciples and the various evil spirits.

An entertaining fantasy, Mr. Vampire was a big critical and commercial success, spawning several sequels and numerous imitators.

*

If there’s a touch of vaudeville in Mr. Vampire, Ronny Yu’s The Bride With White Hair (1993) aims for elegant epic fantasy. Loosely based on a popular wuxia novel written in the late ’50s, Yu’s film is an elaborately mounted romantic tragedy in which Zhuo Yihang (Leslie Cheung) is tasked with leading the Wu-tang Clan in its fight against an evil cult led by male/female conjoined twins Ji Wushuang (Francis Ng and Elaine Lui). During the conflict, he meets and falls in love with Lian Nichang (Brigitte Lin), an orphan raised by wolves and adopted by Ji Wushuang. Away from the two clans, Zhuo and Lian have a brief idyllic romance.

Lian announces that she is leaving the cult, but us forced to undergo a brutal ordeal as the price – in fact, the intention is to kill her, but she manages to survive, willing to suffer for her love. But meanwhile, Zhuo has returned to find that many members of the Wu-tang have been killed and all the signs point to Lian. When she appears, she swears that she’s innocent and asks Zhuo to trust her, but he has doubts and after a furious fight, she leaves. Then he discovers that it was Ji Wushuang who attacked the clan. Zhuo leaves and waits on a remote mountain in hope that Lian will return to him.

Highly stylized, The Bride With White Hair is full of striking imagery which produces a kind of fairy tale atmosphere; the characters are archetypal and the world they inhabit dreamlike, with Ji Wushuang a monster out of a nightmare. The fight scenes are full of elaborate wire-work, and Eddie Ma’s design and Peter Pau’s cinematography eschew any attempt at realism – it’s largely shot on sets, further removing it from the real world and emphasizing its status as a work of feverish imagination. It was this film, by the way, along with Wong Kar-wai’s Ashes of Time made the following year, which gave me a years-long crush on Brigitte Lin.

*

These releases, featuring good to excellent transfers, are all supplemented with numerous extras, including commentaries and interviews, alternate audio tracks and an alternate cut of Eastern Condors.

Comments