Alex Cox’s Walker (1987): Criterion Blu-ray review

To begin with a personal anecdote: I was in Toronto in September 1992 for a Festival screening of a short film I had been involved with, so I was lucky enough to catch the debut of El patrullero (1991), Alex Cox’s remarkable low-budget feature about an idealistic young policeman who is ultimately crushed by the corruption which surrounds him in the Mexican Federal Highway Patrol. The day after the screening, I happened to see Cox in a hotel lobby and, although I normally wouldn’t have had the nerve, the film festival atmosphere seemed to authorize my intrusion into his personal space, so I walked over and told him how much I liked his movie.

He was friendly and open, so we chatted for a few minutes – mostly about the fluid, constantly moving camerawork; I had assumed that this was all done with a Steadicam, but he told me that such equipment had been beyond the limits of a very small budget, that in fact it had all been done by his cameraman Miguel Garzón with a 35mm camera mounted on his shoulder, which made it even more impressive.

Feeling more relaxed, I told him how much I had liked his previous film, Walker (1987), and had been surprised at its negative critical reception. He said he also thought it was a good movie and even after several years the poor reviews were obviously still a sore point. Although I was a complete stranger to him, my comments provoked a brief but enthusiastic conversation about Walker and his reasons for approaching its historical narrative in the way that he had.[1]

Three decades later, the hostility of the critics doesn’t seem as puzzling. Walker mocks fundamental tenets running through American history and the nation’s self-image. It was not uncommon even as late as 1987 for Americans to dislike or simply misunderstand how the U.S. is perceived from the outside. So much of American history is embedded in unquestioned myths, myths which propel the U.S. to repeat certain behaviours over and over again, often committing acts diametrically opposed to supposed national principles and yet perceived to be expressions of those principles.

This is the subject of Walker – the historical tendency of the United States to crush other countries in the name of bringing freedom and democracy, often destroying genuinely democratic movements in the process and imposing oppressive, autocratic rulers who favour U.S. economic interests over those of the indigenous population. When Cox and his scriptwriter Rudy Wurlitzer decided to make Walker, their project couldn’t have been more timely. Ronald Reagan was in the midst of committing domestic and international crimes in order to destroy the popular Sandinista government of Nicaragua because the recent revolution had overthrown the Somoza regime which, while brutal towards Nicaragua’s own population, was friendly to foreign business interests. Reagan and his minions illegally sold arms to Iran and used the proceeds to fund the vicious, fascist Contras who committed numerous atrocities in their attempts to undermine the democratic government which had replaced Somoza.

Cox and Wurlitzer found the ideal vehicle for their critique of American imperialism in the story of William Walker, an accomplished 19th Century figure – doctor, surgeon, lawyer – who became an adventurer acting on the idea of manifest destiny, the belief that America had been ordained by God to expand across the continent and beyond to spread the principles of the U.S. constitution to “lesser” societies. Walker was only in his early 30s when he took a small force of mercenaries into Mexico to seize Baja and Sonora, declaring himself president. That adventure ended in a rout by Mexican forces and back in California Walker was put on trial for waging an illegal war. He got off, however, because popular sentiment was on his side. In fact, he was something of a celebrity because of his military adventurism.

A few years later, Walker was commissioned by one of the Nicaraguan political parties to provide a mercenary force to defeat their opposition in a brewing civil war. Although the expedition began poorly, Walker eventually defeated the opposition and took the role of commander of the Nicaraguan army. Eventually, he declared himself President and ruled for two years, his most egregious action being the repeal of Nicaragua’s anti-slavery laws in the hope that he would gain support from the slave-holding states of the American south. His regime was eventually defeated when the surrounding countries – Costa Rica, Honduras, El Salvador and Guatamala – joined together to overthrow him. However, instead of returning to the U.S. in disgrace, he was greeted yet again as a hero.

A couple of years later, Walker set off on another expedition, this time to Honduras. Ironically, he was captured by British forces who saw him as a threat to their interests in the region; they turned him over to the Honduran authorities and he was tried and executed in 1860, just 36 years old.

This was the history in which Cox and Wurlitzer rooted their movie, but they weren’t interested in a simple historical narrative; they used it as a vehicle to explore aspects of the American myth and how that myth had shaped, and continued to shape, the actions of the United States politically, economically and militarily. Rather than just an account of historical events, Walker delves into the psychological impulses behind those events. This was something which escaped many contemporary critics – for instance, Roger Ebert, the epitome of the mainstream reviewer, accused the filmmakers of not having a clue what they were trying to say, that Walker was a very bad film which was little more than a smug display of Cox’s sense of his own cleverness.

And yet, if anything, Walker wears its theme very visibly on its sleeve; not only does it know what it’s trying to say, it says it with absolute clarity and precision (which itself was criticized by other reviewers, who felt Cox was merely preaching at the audience). It’s trying to be a comedy, Ebert says, but has no laughs; but it’s a comedy in the sense that it displays the absurdity of the gulf between the self-perception of William Walker (who stands in for the nation itself) and the reality of his actions. Acting with absolute moral certainty, he commits absolutely immoral acts, using his rigid protestant religion as a justification.

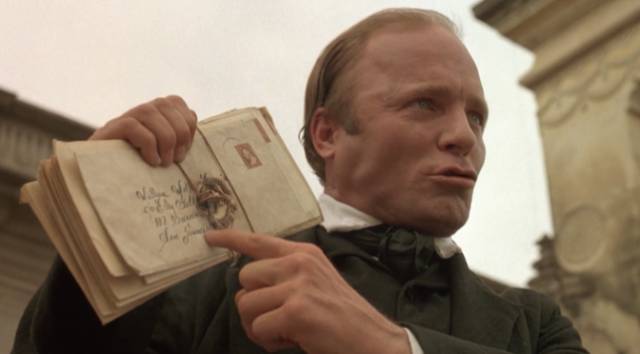

The film begins in the midst of a bloody battle as Mexican forces close in on Walker’s tiny force; everything is lost and Walker (Ed Harris) addresses his men about the nobility of their cause, about being betrayed by the U.S. government which had not provided support, saying that only an act of God could save them now – at which point a storm suddenly rises, providing cover for their escape. This coincidence inevitably reinforces Walker’s sense of his own righteousness.

After his trial in San Francisco, we find ourselves at a soiree in his fiancee’s house where Ephraim Squier (Richard Masur), a minion of robber baron Cornelius Vanderbilt, holds forth about the current political situation, which includes a defence of slavery. Walker’s fiancee, staunch abolitionist Ellen Martin (Marlee Matlin), is furious. However, being deaf, her objections via sign language are incomprehensible to Squier. Translating for her, Walker waters down her anger and insults, amplifying her fury, and she storms out of the room with Walker hurrying after her.

He tries to justify not offending Squier by saying that he’ll need Vanderbilt’s support for his own political ambitions. During this conversation, it becomes clear that Ellen has unshakable moral positions, while Walker is actually weak and insecure beneath his childish braggadocio. She is the conscience which makes him uncomfortable because he is unable to live up to its standards.

When he is summoned by Vanderbilt (Peter Boyle), who proposes that Walker lead a force to Nicaragua to “stabilize” the country to protect his business interests (Vanderbilt has a monopoly on transporting goods across the isthmus between the Atlantic and Pacific), Walker turns him down because he plans to marry Ellen and start a newspaper – but when he returns home, he discovers that she has died from cholera. In his rage against God – and against Ellen herself for this “betrayal” – he takes up Vanderbilt’s proposal and sails to Nicaragua with a small force of mercenaries. This grand military/political adventure is a turning outward of the emotional pain which he has no other way of dealing with.

Driven by the absolute certainty of his righteousness, Walker ignores rational advice about strategy and tactics. He leads his men into their first battle without regard for anyone’s safety, resulting in a slaughter … and yet the opposition collapses despite his incompetence and he assumes power, rejecting the presidency but taking the role of commander of the army, while himself naming the new president.

He is taken as a lover by Doña Yrena (Blanca Guerra), an aristocratic woman who is drawn to power, but nonetheless amused by his immaturity. Unfortunately, the man named president is also her lover, so in jealousy Walker has him executed, provoking outrage and grief among the populace and not surprisingly failing to secure Doña Yrena’s undivided affection.

The more power Walker gains, the more he slips into outright megalomania; believing himself favoured by God, whatever whim grips him is seen as a divine right. His increasingly extreme actions alienate his most devoted supporters, the final tipping point being his proclamation that slavery will now be legal in Nicaragua. Without any moral anchor, he betrays every principle he once claimed to hold, the accumulation of power being his only aim. He has smashed the previous social and political structures of the country and replaced them with nothing but arbitrary, ever-changing personal whims. He even betrays Vanderbilt by granting the transportation rights to his rivals – a step too far. It turns out that Walker himself was merely a puppet of those American capitalist interests, his messianic impulses manipulated for their purposes. Religion is merely a useful tool for irreligious business and political concerns … as it remains today.

As in so many of America’s imperial adventures over the ensuing two centuries, Walker’s subjugation of Nicaragua was unsustainable because in its single-minded focus on those American business interests it was completely blind to all the indigenous factors which shaped Nicaragua as its own nation. Empire is blind to the nature of those it strives to dominate; manifest destiny becomes a brutally destructive impulse which repeatedly backfires, inflicting damage on those who pursue it.

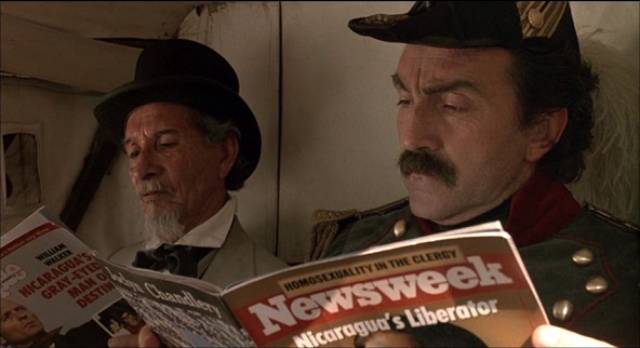

The overt political points being made by Cox and Wurlitzer rubbed many critics the wrong way – this was agitprop, a left wing diatribe which violated the first law of Hollywood movie-making: leave the messages to Western Union. One strategy in particular gave offence – the use of deliberate anachronisms which increasingly break the illusion of a self-contained period. These transform Walker into an intellectual argument rather than a colourful entertainment.

The first instance – during the initial battle in Nicaragua Major Hennington (Rene Auberjonois) pulls out a Zippo lighter to ignite a fuse – seems like a jarring lapse in continuity; this prop wouldn’t have been invented for almost a hundred years, associated with World War Two rather than pre-Civil War America. But it soon becomes clear that this was no error, but rather a deliberate strategy. When the president is executed, the crowd press forward and cover the body with obviously plastic flowers. And then we see characters reading copies of Newsweek, People and Time with Walker on the cover, headlines proclaiming his heroic exploits and declaring him Man of the Year. When Doña Yrena leaves the city after attempting to kill Walker, her carriage is passed on a dusty road by a speeding Mercedes – this last a reference easily grasped by a Nicaraguan audience if confusing for viewers in the States: deposed dictator Somoza had owned a Mercedes dealership.

The final straw for those irritated by Cox’s “cleverness” is the climactic arrival of helicopters which pluck the survivors of Walker’s force from the city he has set on fire, an inescapable visual reference to the ignominious American rout from Saigon. All of these details shatter any illusion that the events of Walker are safely contained in the distant past, as is generally the case with historical epics. Parallels are not cautiously suggested, but rather thrust in the audience’s face. But Cox goes even further as the final credits run; television news coverage of Reagan’s propaganda about Nicaragua plays, his offensive claims that the murderous Contras were freedom fighters given the lie by disturbing images of their civilian victims. Here in the 1980s, the U.S. government is carrying on Walker’s project of claiming ownership of another country in the name of cherished principles which conceal nothing more than crass economic interests which view that other nation’s population as merely an inconvenience.

Walker is a justifiably angry film which violates numerous mainstream norms to make its moral case against imperialism. And yet despite the negative responses of offended critics (and a studio which quickly dumped it), it is finely crafted with wit and emotional power. The cast is excellent – Harris was never better than here, capturing the chilling madness of a man consumed by a religious conviction which provides the justification for committing horrendous acts. Despite appearing only briefly, Marlee Matlin gives Ellen a fierce moral authority which serves to illuminate Walker’s weakness and hypocrisy. As Doña Yrena, Blanca Guerra provides a similar contrast; strong and intelligent, she has a much clearer grasp of political realities than Walker, although her interests lie in maintaining the power of the social elite to which she belongs.

While character in Walker is essentially a matter of archetypes rather than individuals, the ensemble cast provides vivid sketches. What they don’t do, apart from the two women, is give us any conventional figures to identify with. Walker, while central, is no hero; in fact he’s a monster. Xander Berkeley might serve as protagonist in a more conventional movie as reporter Byron Cole who attaches himself to (or, in modern terms, embeds himself in) Walker’s private army, but he doesn’t stand apart as an independent observer, rather becoming a participant in events, himself implicated in the horrors being perpetrated. Auberjonois as Hennington is a far more astute strategist than Walker, but his advice is never accepted – and yet he remains, repeatedly wounded but never abandoning the madman he follows. Peter Boyle as Vanderbilt is another kind of monster, driven only to accumulate wealth and power and revelling in the humiliation that power and wealth permit him to inflict on everyone around him.

If there’s one character other than the two women who might lay claim to audience identification, it would be Sy Richardson’s Captain Hornsby, Walker’s enforcer who keeps the ragged army as much in line as possible, and yet suffers his commander’s most egregious betrayal when Walker, who has previously espoused principles of freedom and equality, announces the institution of slavery in Nicaragua. And yet, this Black supporter doesn’t rebel or abandon Walker, staying on instead until his disillusioned loyalty results in his own death.

Two more common complaints bear mentioning: many reviews expressed distaste for the film’s graphic violence, all that spurting blood. An obvious visual reference to Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969), it seems odd that people were still complaining two decades after that landmark movie changed the way Hollywood treated violence. (Just a decade later, far worse was being praised for its realism in Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan [1998].) Even less explicable was the dismissal by some critics of Joe Strummer’s score, which provides a melancholy and lyrical counterpoint to that violence. It surely ranks among the all-time greats which lift a movie to a new, more complex level beyond what’s inherent in the script and visuals.

*

The disk

Criterion’s new hi-def master obviously improves on their 2008 DVD, with vibrant colour and a detailed image, marred only by large, intrusive burned-in subtitles for Spanish dialogue and sign language – this apparently due to the transfer being sourced from an interpositive rather than the original negative. The mono soundtrack is excellent, particularly with regard to the unconventional use of Strummer’s quiet score which takes primacy during many of the bigger action scenes.

The supplements

The new edition duplicates all the original DVD release’s extras, with the addition of a couple of short pieces by Cox – Walker 2008 (6:26), in which the director reads excerpts from the bad reviews; and On the Origins of Walker (16:07), in which he goes through old notebooks and speaks about how the film was developed.

The archival extras include a commentary by Cox and Wurlitzer in which they talk about the history of William Walker, their approach to the material, the experience of shooting in Nicaragua in the midst of the war against the American-financed Contras, the cast and the negative critical reception.

Dispatches from Nicaragua (2008, 50:40) is a documentary by Terry Schwartz edited from tapes shot during production, but only completed two decades later. It’s as much about the situation in Nicaragua at the time and the significance of making the film on location as it is an account of the actual shoot. On Movie-making and the Revolution (2007, 11:13) is an audio reminiscence by an unnamed extra (written by Linda Sandoval and read by Miguel Sandoval) which provides an account of the shoot from the point-of-view of someone at a low level on the production. The Immortals (8:51) is a montage of behind-the-scenes stills set to Strummer’s music.

There’s also a trailer (1:46) and a thick booklet with many stills, an essay by Graham Fuller, and an account by actor Linda Sandoval of a gruelling initiation in which Cox and members of the cast made a trek on foot through remote mountainous country to get a sense of what Walker’s men might have experienced. The introductory section of Wurlitzer’s book about the production is also included, combining sections of the script, excerpts from Walker’s own writings about his expedition, and quotes from Ed Harris’s diary of the shoot.

*

Walker, Cox’s best feature, has unfortunately only gained in relevance since it was made, and Criterion’s upgraded edition comes at a time when its deconstruction of American mythology is needed more than ever as the American right spirals into fantasies of an ahistorical past fuelled by religious extremism.

___________________________________________________________

(1.) As I was then still connected to the Winnipeg Film Group, I tried to trade on that brief encounter by proposing that Cox come to Winnipeg to do a workshop for us, possibly focusing on creative approaches to overcoming a small budget. Although there was some interest, we never managed to iron out the details or find a viable schedule. (return)

Comments