(Faulty) Memory and the formation of a passion for movies

As I mentioned two weeks ago, a couple of times a year I get together with a group of friends and we talk about what we’ve been watching since the last meeting. We spent a long evening yesterday with a slightly different agenda. John had suggested that we dig back into our memories and think about the movies which left some mark during childhood, leading to a more mature and conscious approach to film as we grew older. This wasn’t about recalling our first experiences of seeing what we now know are great or important movies, but rather about our personal interactions with cinema per se.

Over dinner (hamburgers and salad, with a choice of wine or beer), we chatted about frustrations with our various jobs, then after dessert we got down to the work of the evening. I didn’t do any particular research myself, just poked about in my memory to see what stands out, but John began with a year-by-year list from around 1959 to the end of the ’60s. Wikipedia has some useful resources for a project like this in the form of pages covering U.S. and British releases by decade (the period covered had next-to-none Canadian releases), and he’d gone through these lists looking for titles that triggered some kind of response.

Howard ended the evening with a similar list, though his research had largely involved going through newspaper archives at the library and he talked about numerous double-features he’d seen at various theatres. Not surprisingly, the B part of the bill, which held little interest for him at the time, often turned out to be the more interesting movie in retrospect.

Dave took a different tack, less about the films themselves and more about the experiences he had going to the movies, while Bev had a list which, unlike the rest of us, almost completely lacked fantasy, horror and sci-fi movies.

There were some interesting patterns as well as differences. For instance, all of us had very early Disney experiences, though the particular films varied[1]. Although the other four all grew up mostly in Winnipeg, I began in England and, after twelve years, moved to Newfoundland, and yet had seen a lot of the same movies as the other three men in the room. In fact, as the evening progressed from John to Dave then Bev, the repetition of titles suggested a kind of shared imaginative world which transcended our different real-world circumstances. And again and again, I was vividly reminded of my own experience of movies I hadn’t thought of – 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and Operation Crossbow came up several times, both movies which had an impact on me (the former obviously in re-release, probably when I was about seven or eight; the latter first-run when I was ten).

John, Dave and Howard all had early experiences with the Bond movies, but as I was still in England at the time, Dr. No, From Russia With Love and Goldfinger were inaccessible to me because they were restricted. My first Bond experience had been Thunderball, considered more acceptable for kids and partly because of that a step down from the first three – more adventure, less nastiness. Strangely, I was the only one who had continued to watch the Bond movies through the character’s various incarnations (up to Skyfall, at which point even I couldn’t take it any more); John stopped after You Only Live Twice, Howard after Live and Let Die.

For what it’s worth, here’s my own list of memories, compiled off the top of my head without any further research – though the evening has prompted an interest in digging a bit deeper.

*

First of all, a general impression. I lived in a small Essex village about ten miles from Chelmsford, where there were three cinemas: the Odeon and the Regent, which were larger, with balconies, where I saw most of my childhood movies, and the smaller Pavilion which had only one level of seating and where I probably went only once or twice before emigrating. Trips to the movies always included a packed lunch – I specifically recall a lot of egg sandwiches – and at intermissions usherettes would walk through the theatre with trays of drinks and ice cream. The ice cream was usually a block of vanilla between a couple of wafers and the drink was Kia-Ora, a vaguely orange-flavoured, slightly syrupy beverage which came in plastic cups sealed with tin-foil.

Shows were usually double-features, with the B half being a low-budget English programmer. I can’t recall any specific movies, but have distinct memories of English streets and small cars in black-and-white, and stories which usually involved some kind of crime. These stood in sharp contrast to big-budget colour movies which had an epic quality.

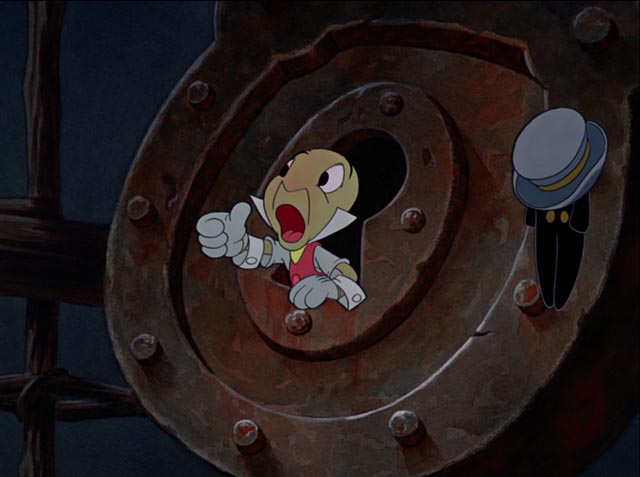

But my first clear memory, from when I was five or six, was of a field trip with my class from the village school to see Disney’s Pinocchio at the Odeon. I have two vivid memories of the movie – one of which turns out to be completely false: the first is the sequence inside Monstro the whale, the second is of Pinocchio getting angry and throwing something at Jiminy Cricket, squishing him, with Jiminy returning as a ghostly manifestation of Pinocchio’s conscience. Apparently, that’s what happens in Carlo Collodi’s 1881 children’s novel, but I have no memory of ever reading the book.

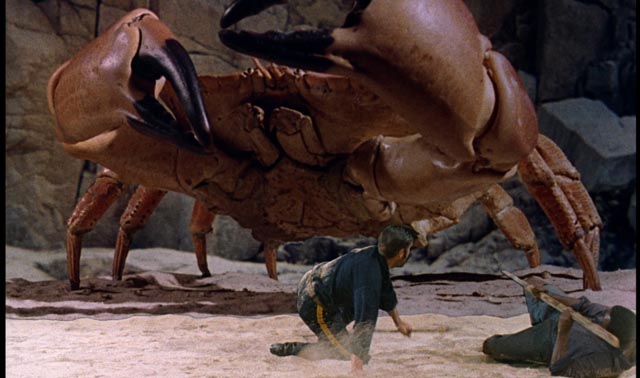

I, like John, Dave and Howard, received some powerful formative experiences from Ray Harryhausen. I must have seen The 7th Voyage of Sinbad when I was about four, but my memory conflated it with Jason and the Argonauts, which I saw when I was eight. Years later, in seeing Jason again, I was puzzled at the absence of the vividly remembered Cyclops encounter … which, of course, is actually in 7th Voyage.

My strongest memories of Harryhausen are of seeing The Mysterious Island when I was six or seven (the best-directed of Harryhausen’s films, with Cy Endfield in charge), Jason when I was eight, and First Men in the Moon when I was nine or ten. The English setting and characters of the latter were significant to me at the time, but in seeing the film again in subsequent years I find the excellent fantasy elements somewhat undercut by too much forced comic relief.

When I was ten, I saw Jack Cardiff’s The Long Ships – I was surprised to discover that I was the only one in the room who’d seen it, although several of us had seen Richard Fleischer’s The Vikings. Unlike that movie’s quite serious treatment of the Norsemen, The Long Ships is a far-fetched adventure in which vikings travel to North Africa in search of a fabled treasure. The one thing which really stuck in my memory was Moorish king Aly Mansuh’s preferred method of execution – the “steel mare”, a long razor-sharp blade in the shape of a curved horse’s neck with a spring-loaded platform at the top and a second platform featuring long spikes at the bottom. A prisoner would be tipped off the upper platform, slide down the blade and end up in pieces on the spikes below. Pretty gruesome stuff for a ten-year-old (though not depicted explicitly, of course).

That same year, I also saw Cy Endfield’s Zulu, which really impressed me. I particularly recalled the ominous sound of the massed Zulu warriors banging their spears on their shields, making a sound like a giant express train as they approached the small English fort, and the rotating firing line of the Redcoats as they kept up continuous fire by having one rank firing while another was reloading, then switching. While there are obvious issues with the film’s colonialist politics, for a ten-year-old boy it was an impressive adventure about heroic characters fighting overwhelming odds.

The next year, I finally saw my first James Bond movie, Thunderball. Because the earlier movies had been forbidden, there was a definite sense of achieving a new level of maturity in being let in to see it and that supplied an air of excitement which carried me through the sluggish underwater action. Perhaps my most vivid memory was of Bond taking one of the attendants at the country mansion spa into the steam room, where you could see her clothes being slipped off with her back pressed against the frosted glass wall. One of my earliest suggestions of sex on the screen!

That same year, another movie provided a very slightly more explicit sexual image. In Henry Levin’s Genghis Khan there’s a scene in which a group of warriors take a communal bath in a big tub with some women and when they splash around, there are brief glimpses of bare breasts – a kind of physical shock when you’re a young boy sitting in the theatre beside your Mum and Dad.

Somewhat more innocent was my first movie crush – which it turns out was shared by a couple of other people in the room last night. I first saw Hayley Mills in Pollyanna when I was about six. This film and its title character has always had something of an undeserved reputation for saccharine piety, yet it’s actually a quite dark and critical portrait of smalltown life. Rather than sentimentally idealized, this community is shot through with pettiness and suspicion, but young Pollyanna has yet to be tainted by that atmosphere; she wants the best for people and suffers for it. The fact that she holds on to her optimism isn’t a sign of naivety so much as of her strength and resilience.

The next year, Bryan Forbes’ Whistle Down the Wind reinforced my budding infatuation by returning Hayley Mills to England and a countryside not much different from where I lived. While the film’s allegorical elements may seem a bit too overstated now, for a seven-year-old boy it was a dark and powerful dramatic experience focused on kids very much like me and my village friends.

Then the next year Hayley appeared in Robert Stevenson’s kids’ adventure In Search of the Castaways as an English girl who sets off in search of her sea captain father who had disappeared off the coast of South America. In these three movies, Hayley Mills, eight years older than me, covered a wide range of experiences with an indomitable spirit which I found irresistible.

*

Although it violated the rules of the challenge, I (and a couple of others) did mention some television experiences. First was a weekly half-hour program called (I think) Cinema (possibly hosted by Derek Malcolm, although that’s definitely an unreliable memory), on which clips of new releases were shown with a few critical comments (kind of a proto Siskel & Ebert). In particular, I recall a clip from Hammer’s The Gorgon, when I would have been nine. It was a scene in which a sheet-shrouded body was being wheeled into the morgue on a gurney; a hand sticking out from under the sheet bumped the edge of a table and shattered … I was frustrated because, of course, Hammer films were restricted in England so there was no chance of my seeing it, but my sister did go and told me about it.

The second clip I remember, which may have been in a retrospective episode, was of a scene in Wolf Rilla’s Village of the Damned (originally released in 1960). This was the scene in which the alien children are walking down a country lane in a group and, as they pass a farm worker, the man mutters something under his breath. The kids stop, turn and stare at him with their glowing eyes, and he slowly raises his shotgun and blows his own head off. It was a good ten years later before I got a chance to see the whole film, and it was worth the wait.

And two features I first saw on television (a small black-and-white set in our living room) were the original King Kong, which totally thrilled me, and Val Guest’s Quatermass II, which totally chilled me … both going a long way towards cementing a life-long love of fantasy and horror.

*

Once settled in Newfoundland, I lived about the same distance from St. John’s as I’d previously been from Chelmsford, so going to the movies still meant a half-hour bus ride. Again, I think there were three theatres, though I don’t recall the names. I’d occasionally go into town with my best friend Don and we’d spend a Saturday afternoon watching mostly re-issued movies.

There was The Longest Day, which impressed me with its scale and its long series of isolated vignettes about horror and heroism. On another Saturday, there was a triple feature of Dr. No, From Russia With Love and Goldfinger, all played back to back without a break. That was probably around 1968, so I’d have been about thirteen – still too young to see those movies if I’d been in England. Then and now, I considered Goldfinger the best of the Bond films – it has the best villain line in the whole series, as Bond is strapped to a table with a laser slowly working its way towards his crotch; Goldfinger heads for the door and Bond says “You expect me to talk?” and the villain pauses to glance back, saying “No, Mr. Bond. I expect you to die” in Gert Fröbe’s wry German accent.

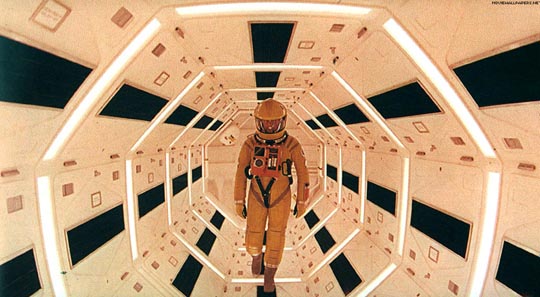

Also in 1968, of course, I saw 2001: A Space Odyssey and I’d never had that kind of experience before. I can’t say I knew what it all meant, but I was totally immersed in the film’s world – its evocation of space has never been equaled, let alone surpassed. It’s broad historical sweep, its suggestion of a vast universe beyond individual human comprehension, was awe-inspiring. Though I was only fourteen at the time, I actually wrote a letter to the St. John’s Evening Telegram to take a reviewer to task for daring to call it pretentious and boring.

That was also the year of Planet of the Apes, a very different kind of fantasy, beginning with epic adventure before bogging down a bit in self-conscious satire courtesy of co-writer Rod Serling. Still, it remains a favourite, even its flaws viewed with affection.

It was either that year or the next that I went to my first drive-in (no such things existed in England). I can’t recall who I went with, but the show was Roger Vadim’s Barbarella, which to an adolescent was exotic and erotic. I still like its pop art design and cheesy comic book tone, and some parts haunt my imagination – particularly the sharp-toothed killer dolls that attack Barbarella, tearing through her costume and leaving streaks of blood on her legs, and the evil queen (Anita Pallenberg, voiced with sultry knowingness by Joan Greenwood, the sexy comic lead in some of Ealing’s best films) in her chamber floating inside the sentient ocean, Matmos.

And speaking of budding sexuality, I was perhaps fourteen, no more than fifteen, when I got in to see Mac Ahlberg’s I, a Woman, a gauzy black-and-white Swedish film about a woman’s sexual awakening. It was the kind of artful exploitation that was gradually chipping away at Production Code restrictions. Ahlberg, a cinematographer as well as director, eventually ended up in the States where he shot some of the best second-wave 3D in the early ’80s for Charles Band’s Parasite and Metalstorm. Regardless of the movies’ other qualities, Ahlberg’s 3D photography was technically inventive (I particularly remember his handheld work in Metalstorm, violating rules about 3D needing to be stable to prevent audience disorientation).

*

Television in Newfoundland at the time was a bit strange. The local CBC station often showed movies at 11:00AM which I’d watch if I was home sick from school, and I’d see French films with nudity and sex; but most surprising perhaps was what I came across unexpectedly one afternoon (I recall it as a Wednesday), probably when I was in grade eight, so perhaps early in 1968. They showed movies at 3:30 or 4:00 and I’d be home in time to watch. On this particular day, what I saw was Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, a pretty disturbing experience for an adolescent.

*

As I’ve mentioned here before, the early-’70s were when I really started to become aware of the ways in which films are constructed, how technique embodies meaning … the same story can come out very differently depending on how it’s filmed. (Just compare Roy Del Ruth’s 1931 version of The Maltese Falcon with Huston’s 1941 version; they have virtually the same script, both sticking close to Hammett’s novel, yet there’s no comparison – it’s not just that Ricardo Cortez is no Bogart; it’s how Huston stages scenes, the way Arthur Edeson photographs them.)

In 1972, there were significant encounters with The Godfather (at the Avalon Mall Cinema in St. John’s) and A Clockwork Orange (in the vast Warner West End in Leicester Square, London), which was well into a months-long run before eventually being withdrawn at Kubrick’s own insistence (it wasn’t shown again in England until after the director’s death).

But 1973 was the critical year when I really started watching consciously, immersed yet standing back to observe how a film was making me feel the way it did. There was Mean Streets with its restless camera and its characters’ moral conflicts dramatically externalized; there was Badlands with its classically controlled visual style in constant conflict with the overly romantic subjectivity of Holly’s voiceover which comments on and counterpoints events we react to objectively with horror; there was Don’t Look Now with its deconstructive editing technique which shatters and constantly recomposes physical space to evoke an unstable psychological space, its tricky fracturing of time and memory, all in service of dissecting John’s tragic lack of self-awareness compounded by crippling grief; and Electra Glide in Blue, which uses classic western imagery to infuse the life of an ambitious but doomed highway patrolman with a mythic quality which transforms sad and pointless events with an air of genuine tragedy.

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) Which raises the issue of the extent to which commercial entertainment has colonized our imaginations; to what degree our experience of the world has been shaped by these corporate products. Disney and James Bond and Ray Harryhausen were key figures in the development of our boyish taste (but not for Bev’s). This manifestation of mass, communal imagination is even more ubiquitous today. Although I find superhero movies tedious, I’ve nonetheless seen many and am unavoidably aware of many more … and I still get suckered in by the media frenzy which greets “radical departures” like Wonder Woman (2017) – finally a woman-centric superhero movie! – and Black Panther (2018) – finally a Black-centric big-budget superhero movie! – and Logan (2017) – the superhero movie as Shakespearean tragedy! And yet they all turn out to be the same tedious, generic product of a mass-market machine which endlessly recycles plots and characters which have become so familiar as to be meaningless … but are nonetheless impossible to avoid. (return)

Comments

I don’t usually think about it, because you seem as immature as me after a scotch or two, but you are definitely older.

Of these movies, I can recall being influenced (by that I mean dreaming of or having nightmares about) Village of the Damned and 2001. The others I saw only on TV, usually black and white. I can count on two hands the movies I recall seeing in theaters, while living in Scotland: The ones that helped form my appreciation of movies were only a small subset of those: 2001 (seen at 8 years old), The Trap, around the same age, Island of Terror (seen on TV and the cause of many nightmares), The Prisoner (a TV show, but a huge influence on my tastes), Dr. Who, The Saint, Man in a Suitacase. It’s likely that my taste in movies was dictated almost entirely by what I watched on TV as a child. Not to mention Lost in Space, Batman, Dr. Who, Star Trek, Twilight Zone, Night Gallery and The Outer Limits.

As children, we didn’t go to many movies. Those we did see were family affairs: The Sound of Music, Oliver, Pinnochio, 101 Dalmations, etc. These were fun, but it wasn’t until coming to Canada, and taking the bus downtown on Saturdays with my brother (me 10, him 8) and seeing the forbidden movies: Frogs, Tales from the Crypt, French Connection, The Seven Ups, Duck You Suckers, Prime Cut, and others… that my true taste in movies developed.

My children, on the other hand, have been completely warped by the movies you have brought over on Saturday nights.

TV is a whole other thing of course. We all saw way more TV than movies as kids because we watched every day, often for hours. Here are some titles you probably don’t remember (or never even knew) that were a big part of my early years: Cannonball (two guys having adventures on American highways driving a semi); Whirlybirds (some guys having adventures flying a helicopter), Flying Doctor (Australian, I think, set in the Outback), Garry Halliday (another pilot). I loved Perry Mason and Dixon of Dock Green (English village policeman), recall vividly the BBC’s Sherlock Holmes starring Douglas Wilmer (still my Sherlock). Dr Who, of course, which I watched from the very first episode … William Hartnell is the only Doctor for me. Then there were some of the ones you mentioned: The Saint, Danger Man, The Third Man, The Prisoner, Man in a Suitcase, The Persuaders … one of my favourites was Crane (aka A Man Called Crane) about a smuggler in North Africa. Room at the Top starring Kenneth Haigh (possibly the first time I heard the word “shit” on television). Comedies: Hancock’s Half Hour, Steptoe and Son, It’s a Square World … and a bit later Monty Python, Clochemerle … A rich and varied feast …

And of course not to be overlooked are the works of Gerry and Sylvia Anderson: Four Feather Falls, Fireball XL5, Supercar, Stingray, Thunderbirds, Captain Scarlet, Joe 90 and the live-action UFO … definitely a major part of my childhood imaginative experience. (Though I was never a fan of Space 1999.)