Ken Loach’s I, Daniel Blake (2016): Criterion Blu-ray review

For centuries – at least since the the Norman invasion in the Eleventh Century – Britain has been shaped, defined and cursed by a system of class stratification. The few at the top have ruled with impunity, while the many at the bottom have been suppressed, frequently crushed, demonized and criminalized. This system has undergone various upheavals, but it has been so deeply internalized that the masses seldom became aware of the power of their own numbers; while the occasional revolutionary movement sent chills through the ruling class, few triggered genuine change. Even the Magna Carta, a document which laid the foundations of English Common Law, was an agreement between factions at the top – limiting the King’s power in favour of the land-holding nobility.

Not surprisingly, class has been one of the overriding themes of English art and, particularly, literature. Even Shakespeare managed to inject a critique into his work, although always within the tricky bounds of his time. The lower classes were most likely to be used as comic counterpoint to the dramas of their betters, but he returned again and again to the theme of corruption within the ruling class – though often in the distant past, or if closer to the present then in the service of discrediting the current regime’s rivals.

With the coming of the Industrial Revolution and the transformation of the rural peasantry into an urban working class, the divisions between rulers and ruled became more sharply visible. Historically, the oppressed had their bonds to the land, to a particular place, which gave their hard lives some sense of continuity. Movement to the cities, into filthy crowded slums, and a precarious dependence on their own undervalued labour, destroyed even that problematic security. The divisions between rulers and ruled were thrown into ever harsher relief; and the project of illuminating and critiquing the structures of the system began, building towards the work of Marx and Engels which would make it impossible ever again to maintain the fiction of some divine order within which each person had a clearly defined position and role.

Along with this urbanization, something potentially equally as dangerous began: the rise in literacy among the lower classes, with a concomitant increase in self-awareness. The explosion of publishing and consumption of books in the 19th Century quickened this process. Trashy penny-dreadfuls and respectable literature alike created an image of social horror and corruption which ate away at the official view of a stable social order. The underclass steadily gained an understanding of its innate power, the formation of labour unions embodying a collective determination to resist economic enslavement. The response of their rulers – or as they liked to see themselves, “betters” – was an increasing determination to criminalize the poor and working classes, a project buttressed by contrived moral teachings which attempted to stem the tide by asserting a God-ordained order which justified the rulers’ harsh dominance.

While the 19th Century, roughly corresponding to the Victorian Age, gave rise to social reformers and artists who codified existing conditions – Henry Mayhew, Charles Dickens, George Eliot, among many others – the ruling class doubled down on an official morality which was violated routinely by their own members even as it was used to suppress revolutionary impulses from below. There was so much power in this system, with its roots going back centuries, that the lower classes maintained some kind of deference even as their contempt for their “betters” grew. Indeed, this internalized system was what enabled England to establish and expand its Empire around the world; without lower class investment in the belief that Britain was Great, the vested interests at the top could never have maintained their power in far-flung colonies. Only by instilling a belief in the Empire’s soldiers that they were superior to subject races by dint of being British could the Queen Empress’s authority be maintained.

But the strain caused by the corruption of the Royals and their political enablers inspired increasing contempt and the deference of the lower classes to the Queen couldn’t survive her death and replacement by her debauched son Edward VII. The unstable social contract was finally shattered for good by the First World War, four years of senseless slaughter which represented the death throes of a moribund imperial system in which rival rulers expended the lives of their subjects in order to assert their power against one another. The traumatized working class men who returned from the trenches brought back with them a revolutionary impulse which fed into a politicized union movement; when this culminated in the General Strike of 1926, Britain’s rulers cracked down with savage violence, but the conflict between the classes couldn’t be re-contained and for the next fifty years political power regularly shifted between the traditional landed class and the working class. (Ken Loach documented this war-to-strike upheaval in a remarkable series of four feature-length films for the BBC in 1975; written by Jim Allen, Days of Hope triggered outraged responses from many with a vested interest in the Establishment.)

During this period, labour often felt betrayed by Labour as their political representatives too often settled comfortably into the role of rulers. But working class power was decisively shattered by the government of Margaret Thatcher in the mid-1980s when the national Miners’ Strike was crushed, permanently weakening Britain’s unions and stripping workers of much of their political power. In concert with Ronald Reagan in the United States, Thatcher laid the groundwork for a new social order which replaced a traditional aristocracy with a rapacious moneyed class; we still live with the consequences of this international neo-liberal order, which maintains itself by undermining the social, economic and political power of the working class.

This long-winded preamble is by way of providing the context within which British filmmaker Ken Loach has worked for the past fifty-plus years; not simply one of Britain’s most consistent and productive directors, he has been the key cinematic chronicler of British class conflict from the point of view of those who struggle with the consequences of a system designed to hold them down. Loach, emerging from a Middle Class background, studying law at Oxford, entered the theatre as an actor as a young man and became a director on BBC television in his late twenties. Although he began on episodic series, he found his voice quickly in a series of plays which realistically depicted social conditions among people at the lower end of the class structure. As collaborator Tony Garnett, who produced several of these, says in a documentary on Criterion’s Blu-ray of I, Daniel Blake (2016), they had to work by subterfuge to hide from the BBC what they were really doing because the broadcaster was leery of challenging its political masters.

From the start with these plays and throughout Loach’s career in features, he hasn’t wavered from his project of confronting illegitimate power and treating the poor and working classes with empathy and respect. This may not seem particularly radical, but the tradition in British cinema and popular culture has been to show deference to the upper classes while relegating the working class to a role as comic relief. Loach has been attacked from the right throughout his career as a “propagandist”, a “socialist”, and (as a newspaper headline glimpsed in the documentary puts it) someone who “hates his country”. This reaction to his work merely illustrates how deeply ingrained class interests remain. To the establishment, empathy for the poor is a dangerous and radical position.

As a filmmaker, Loach had difficulty launching feature projects in the ’80s (he made Looks and Smiles in 1981, and Fatherland in 1986, but otherwise just made a handful of documentaries, mostly for television), partly because of his political position. When he finally returned in 1990 with Hidden Agenda, a thriller set in occupied Northern Ireland, the film was initially considered unreleasable because its criticism of British policy was interpreted as propaganda for the IRA. But it proved successful enough to relaunch his career and he has worked steadily for the past two-and-half-decades, creating a body of work which ranges from the intimate – Raining Stones, My Name Is Joe – to larger-scale dramatic depictions of historical events – the Spanish Civil War in Land and Freedom, the Irish Troubles in The Wind That Shakes the Barley. Laced with both humour and anger, Loach’s films have illuminated the ways in which ordinary people are abused by the power of the state, his didactic purposes always tempered by his deep empathy for his characters. This humanization of ordinary people is perhaps the most radical thing about his work and the reason he has continued to offend the establishment.

After his film Jimmy’s Hall (which was set in Ireland during the Depression), Loach announced his retirement at the age of 78 in 2014, but the re-election of David Cameron’s Conservative government in 2015 drew him back. With the neo-liberal assault on society ramping up, Loach and frequent collaborator Paul Laverty (who has worked almost exclusively for Loach, writing all but one of his features since Carla’s Song in 1996) felt compelled to do something to examine the destruction of the support structures the British had relied on since the end of World War Two. A philosophy which was antithetical to the idea that a country’s citizens had a right to economic security, combined with an ideology which placed privatization above social good, served to return Britain to the harsh stratification of the 19th Century. Worship of a moneyed class inevitably fostered a heightened disgust with the poor; once again the system was specifically designed to exploit workers and the poor for the benefit of the wealthy, and poverty itself became criminalized. As with the Victorian moralists, people were poor not because the economic system deprived them of material security, but rather because they had an inherent moral flaw.

What made this new Victorianism perhaps even more vile than the original was that the establishment didn’t even bother to build poor houses as a final harsh refuge for those in need. Instead they established a powerful, increasingly privatized Kafkaesque nightmare deliberately designed to inflict as much suffering as possible on those who could not support themselves with the unreliable, unstable jobs for which they had to compete. The purpose, which the government really made no effort to conceal, was to drive the poorest, least secure members of society to despair and even death (there have been many accounts in recent years of people literally starving or committing suicide); the only rational reason for such a system is that it subdues the lower classes and makes them more amenable to exploitation by those who continue to accrue all the economic benefits available in one of the world’s richest nations.

The film which resulted from Loach and Laverty’s response to this appalling system was I, Daniel Blake, one of the pair’s finest creations. The underlying fury never rises to overwhelm what on the surface is a quiet, sharply observed character study. But the accumulation of indignities inflicted on those characters, the portrait of an insane and malicious system sketched carefully through small details which expand relentlessly to overwhelm these lives, eventually fill the viewer with a sense of rage.

Daniel Blake (Dave Johns) is a carpenter who has worked diligently for forty years, contributing his labour to his community and a chunk of his own modest income to the system which ostensibly exists to aid him if he ever needs support. But when he suffers a heart attack which makes work temporarily impossible, he is drawn into a bureaucratic nightmare whose only apparent purpose is to humiliate him and deprive him of the assistance he desperately needs. In this system, those in need are treated as unworthy, distrusted as probable scroungers and criminals determined to avoid work and responsibility and live an easy life on benefits.

Daniel is in a double-bind. His heart condition in the opinion of his doctor and physiotherapist make it too dangerous for him to resume work, at least for a few months. But an employee of the private contractor managing services in Newcastle, where he lives, after a condescending phone interview which we hear under the opening credits, despite the medical opinion, decides that he hasn’t got sufficient “points” to qualify for assistance based on his medical condition. He’s told that he can appeal, but that process could take months with no guarantee of success. His only other alternative is to sign on for job seeker’s allowance. This entails spending thirty-five hours a week applying for work – pounding pavements, handing out resumes, searching on-line. The catch, of course, is that he’s not actually physically fit enough to work. But in dire financial need, he has no choice but to sign on.

The next obstacle is that he has no computer skills at all. He tries to navigate the application process at the local library, but it keeps glitching and he gives up in frustration. Desperate for help, he returns to the job centre where a sympathetic employee helps him; but before he’s done, the employee’s supervisor intervenes and reprimands the woman; she’s setting a bad precedent by assisting one of their “clients” in this way. Exhausted, Daniel has a brief episode of faintness and the woman sits him down and gets him some water. While he’s recovering, he overhears another “client” having a hard time with the staff. Katie (Hayley Squires) is a single mother struggling to support two young children. The staff treat her pleas for help as “aggression” and order her to leave. Daniel intervenes, and he too is forced out of the job centre. This treatment of any kind of assertiveness as “aggression” becomes a running theme in the film. As employees of the system inflict endless humiliations on applicants, any kind of response other than docile submission is treated as unacceptable and cause for the withdrawal of assistance … yet another way of driving away those in need, and obviously designed just for that purpose.

Mutual need creates a bond between Daniel and Katie and her two kids, Daisy (Brianna Shand) and Dylan (Dylan McKiernan). The warmth which grows as they get to know each other, as Daniel does whatever he can to help Katie by doing chores around her home and sharing his own limited financial resources, is at the heart of the film’s critique of the viciously draconian abuse by the state of the poor. Here generosity and mutual support help these unwanted citizens to survive. But such individual effort in itself isn’t enough to counter the systemically mandated poverty. Katie is pushed by desperation into actions which increase her humiliation, while Daniel is brutally abused by those whose job is ostensibly to offer him aid. Human warmth and affection and caring might make the oppression more bearable for a while, but the individual, severed from group solidarity, can only withstand the brutality of the state for so long.

Because Loach approaches his subjects through a lens of social concern, his artistry may seem almost invisible. But to create such a convincing sense of directly observed reality – observed with the sharp eye of a committed documentarian – requires great skill. In I, Daniel Blake, for instance, he shot the film in chronological sequence, giving the actors their scenes day by day, without allowing them to know where the narrative was going. Because of this, they were responding to events in the moment, as they occurred; moreover, each actor would often not know what the other would be doing – for example, only Hayley Squires knew about Katie’s breakdown in the food bank beforehand. Thus casting is crucial for Loach; his actors have to be deeply and personally engaged with their characters without resorting to artifice. Then Loach observes these naturalistic performances with a sympathetic but objective eye. His art, then, is a collaborative one, as befits a filmmaker with his political perspective.

Although filled with empathy and humour, I, Daniel Blake is a tragedy; an indictment of a horrific economic and political system which demonizes those who survive by hard, but under-rewarded labour. When the wealthy control the social order, just as in Victorian England, those without wealth are despised and viewed as less than human. The power of this film – of all Ken Loach’s work – is that he illuminates the humanity and intrinsic value of lives society has deemed superfluous.

Ken Loach made this film at the age of eighty, but it has the freshness and energy of his earliest work. He invests social realism with nuance and depth, building a rich portrait of Daniel and Katie, and the bureaucratic labyrinth in which they are trapped, detail by finely observed detail. These characters, complex and alive, serve as an irrefutable indictment of a society in thrall to a misconceived and destructive ideology.

*

The disk

Criterion’s Blu-ray is mastered from a 2K scan of the original 35mm camera negative. The image is a clear rendering of Robbie Ryan’s sensitive, unfussy camerawork. The sound is clean, with a minimal use of music, though the accents are rather thick at times, making the optional subtitles useful.

The supplements

Once again Criterion has supported an excellent movie with equally excellent and illuminating supplements.

The disk includes a commentary track in which Loach and writer Paul Laverty discuss the making of the film.

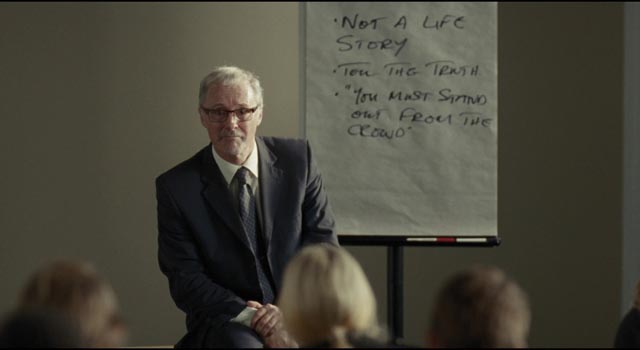

A behind-the-scenes documentary, How to Make a Ken Loach Film (38:07), provides insight into the director’s work with actors – including drawing fine performances from the two children – while the feature-length documentary Versus: The Life and Films of Ken Loach (1:33:45) by Louise Osmand gives an overview of the director’s career and the contentious critical response with which his work has often been greeted. Loach himself comes across as quiet and unassuming, yet absolutely committed to his views about British history and society. It’s not surprising that of all the major British filmmakers of his generation, he should have been the one who stayed with his roots (his sole foray to the States was Bread and Roses [2000], which focused on two undocumented Latina sisters working as cleaners in a Los Angeles office building).

In addition, there are also nine brief deleted scenes (7:45), which add grace notes and touches of humour, but no crucial new information, and a trailer (2:19). The booklet essay is by critic Girish Shambu.

Comments