Twilight Time X 3

Twilight Time has become one of the most notable boutique labels over the past couple of years; with each title limited to 3000 units, collectors feel a sense of urgency with every new release. Available only through the Screen Archives Entertainment website which specializes in movie soundtracks, Twilight Time’s initial focus was on the music, most disks including an isolated score track as the only extra. This has resulted in a sometimes wildly eclectic list of titles – musicals, comedies, costume epics, mainstream entertainment and art films and obscure oddities. More recently, the label has begun to expand the range of supplements on their disks, including commentary tracks (usually featuring Nick Redman and Julie Kirgo, with Lem Dobbs occasionally adding his voice) and occasional documentaries. Three recent releases are John Guillermin’s The Blue Max, Basil Dearden’s Khartoum (both 1966) and Sam Peckinpah’s Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974). The first two, of course, represent big budget, mainstream studio production, while the third stands as a key example of independent transgressive movie-making from that era of destabilized production before the corporations took back the movies with a vengeance in the late ’70s in the wake of Jaws and Star Wars.

The Blue Max (John Guillermin, 1966)

John Guillermin was a fairly prolific director of English B movies throughout the ’50s and into the ’60s. Among the suspense films and Tarzan stories, a few titles stand out – The Day They Robbed the Bank of England (1960); Never Let Go (also 1960), a very nasty little film with Peter Sellers in an uncharacteristic role as the sadistic enforcer for a loan shark; and perhaps most remarkable, Rapture (1965), an intense, elegantly directed black-and-white psychological drama about uncomfortable family secrets, shot in Brittany (also available on Blu-ray from Twilight Time).

Beginning with Guns of Batasi in 1964, Guillermin moved into bigger budgets and more international productions, the kind of thing which became very common in the ’60s. Most of his work from the late ’60s on into the ’80s had all the defects of that model – overblown scripts targeted at a lowest common denominator audience, casts overloaded with multinational stars, and a frequent paucity of imagination. We’re talking Shaft In Africa, The Towering Inferno, King Kong and the like. But at the transitional point between his British films and his international career, somehow Guillermin made his finest movie, combining the best of both strands.

Based on a novel by Jack D. Hunter, The Blue Max is an epic narrative of First World War fliers in which a cynical German infantryman manages to work his way out of the trenches and into the exclusive society of the “knights of the air”, men who rise above the mechanized slaughter of the war in a number of ways, not least in their adherence to a moral code rooted in the idea of gentlemanly combat. The horrors on the ground are irrelevant to them as they joust with enemy pilots whom they respect as much as their own comrades. Lt. Bruno Stachel (George Peppard) cares nothing for their code; his only interest is proving his skills as a way of overcoming his “social defects” (the rest of the squadron are contemptuous of his working class origins).

The conflicts between old and new attitudes, exacerbated when General von Klugermann (James Mason) begins to promote Stachel as a national hero to inspire the German population as the war inexorably turns against them, is played out on a personal level between Stachel, his squadron leader Heidemann (Karl Michael Vogler) and his chief rival in the air, the General’s nephew Willi von Klugermann (Jeremy Kemp). As Stachel racks up his kills, he also seduces the more than willing wife of the General, Countess Kaeti von Klugermann (Ursula Andress), who is also Willi’s lover. The narrative is tightly structured around these personal conflicts and the spectacular aerial scenes are always used to advance that narrative, never merely for the sake of spectacle.

But the spectacle is remarkable. Shot long before computers made anything visually possible, The Blue Max features the finest flying sequences and aerial battles ever put on film. The exhilaration of these scenes captures the strange tension between the pilots’ sense of freedom and the constant imminence of death, a tension which the aristocratic pilots cope with by adhering to their code of chivalry, their precarious balance threatened and ultimately destroyed by Stachel’s brutal pragmatism.

Few of those big budget productions of the ’60s managed to find such a perfect balance of elements and The Blue Max doesn’t feel at all dated today … and it looks stunning on Blu-ray.

*

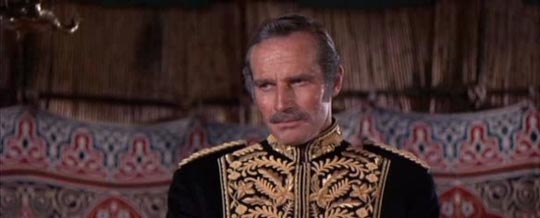

Khartoum (Basil Dearden, 1966)

Made the same year as The Blue Max, with the same kind of international financing and production attitudes, Basil Dearden’s Khartoum is less successful, though not without interest. Obviously somewhat influenced by David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962), Khartoum suffers from a conflicted attitude towards British colonialism. Dearden seems like an odd choice to direct this kind of historical epic – he had a long career going back to the early ’40s, with a series of “social issues” dramas throughout the ’50s peaking with Sapphire (1959) and Victim (1961), dealing with racism and homosexuality respectively. Khartoum stands alone in his filmography in terms of scale and never really manages to find a balance between character and spectacle.

The script was by Robert Ardrey, whose screenwriting career also went back to the early ’40s, but who became best known for a couple of popular, controversial books of anthropology which posited that human behaviour sprouted from our primitive animal roots. Built around two star roles, the film recounts the story of General Charles Gordon (Charlton Heston) and Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah (Laurence Olivier), who declared himself the Mahdi, the prophesied redeemer of Islam, and led a rebellion against the Turco-Egyptian occupation of Sudan in the 1880s. The script does manage to sketch in the complex political background of the revolt and the British reluctance to be drawn into another colonial adventure while Liberal Prime Minister Gladstone was fending off domestic opposition from the Conservatives, but it nonetheless is grudgingly attracted to the colonial enterprise.

Gordon had previously been governor of Sudan during the 1870s; during his tenure he had ended the slave trade and had apparently gained the respect of the Sudanese as a result. Gladstone, as a gesture, persuaded Gordon to go to Sudan although he had no intention of allowing British military involvement in the situation. Gordon’s mission was to evacuate British citizens and others loyal to England. But he had other ideas and his arrival gave the Sudanese the idea that the rebellion would be quelled. Although the film plays down Gordon’s evangelical Christianity, in reality he stayed on because those convictions determined him to oppose the Muslim uprising. Gordon kept hoping that the English would commit to a military intervention, but this ended with a sense of betrayal as Khartoum came under siege and the Mahdi’s army massacred the token forces sent by the British – forces whose only purpose was to extract Gordon to avoid embarrassment back home. Gordon refused to leave and ended up martyred during the climax of the siege.

There are some sweeping, large-scale desert battles in Khartoum, but the film concentrates on creating a parallel between Gordon and the Mahdi, two fanatics whose clash results in a lot of death. Although it’s made clear that the Mahdi’s revolt has some legitimacy as a war of liberation, the film seems unable to avoid making the British officer a noble hero, a man of good intentions who dies for his convictions, validating the Victorian idea of England’s mission to civilize the world, while criticizing the political scheming back home which resulted in the destruction of Khartoum. The ambiguities of colonialism implicit in Lawrence of Arabia (and later critiqued in John Huston’s The Man Who Would Be King [1975]) are here subsumed to the kind of imperial adventure seen in earlier films like The Four Feathers or Lives of a Bengal Lancer. Khartoum struggles to find a way to negotiate between that earlier colonial fantasy and the new realities of a world in which colonialism was collapsing under movements of liberation. It’s ironic to realize that Khartoum was made in the same year as Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers, a fact which makes it seem even more anachronistic.

Twilight Time’s Blu-ray does justice to the film’s colourful visuals (shot by Edward Scaife), but unlike The Blue Max, Khartoum seems very dated, its chief interest being the clashing acting styles of Heston and Olivier, the former stalwart as always while the latter gives an often bizarrely idiosyncratic performance steeped in the residue of his Othello from the previous year.

*

Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia

(Sam Peckinpah, 1974)

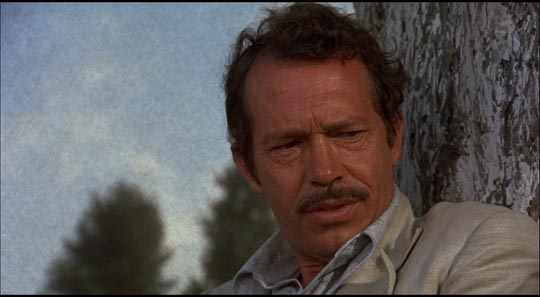

Made for just a fraction of the budgets of The Blue Max and Khartoum, and coming off the relative box office disappointment of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia represented the one time Sam Peckinpah got to make a film without any outside interference, just the way he wanted it. At the time, it also garnered some of his most negative reviews, condemned by many critics as a completely gratuitous exercise in pointless violence. It seems surprising today to realize that, although there are a handful of violent set-pieces, Alfredo Garcia is actually a character study which spends much of its time on quiet, extended stretches of dialogue.

The story is simple: a Mexican patriarch puts a bounty on the head of the man who got his daughter pregnant and a number of people set off in pursuit of the prize, including washed up barman Bennie (Warren Oates in his finest and most substantial performance). This is essentially a reworking of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, a bitter, elegiac dissection of greed and the ways in which it destroys the lives it governs. The heart of the movie is the relationship between Bennie and Elita (Isela Vega), a world-weary whore who loves him and does everything she can to make him see that he loves her and that there are ways they can be happy together which don’t require the windfall money of the bounty. But Bennie believes he needs that money for them to make a life together, his quest destroying both of their dreams along the way.

There’s a looseness, almost an improvisatory tone to Alfredo Garcia, its road movie/quest structure enabling Peckinpah (who co-wrote the script with Gordon T. Dawson) to hang a variety of discursive scenes on the narrative; Bennie undergoes humiliations, moments of physical and emotional pain, and gradually gains a degree of the masculine nobility that Peckinpah sought in his violent adventure stories. Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia distills to its essence Peckinpah’s romantic pessimism and none of the subsequent four features made in the next nine years managed to achieve the creative power of this or the films which preceded it (only Cross of Iron in 1977 came close). But the loose framework also results in a degree of randomness which includes some gratuitously sexist moments; lacking the rigorous structure of Straw Dogs (1971) – which I consider the director’s greatest film – the sexual assault on Elita by a pair of passing bikers seems tossed in merely for the opportunity to get the actress’ clothes off (although it does provide Vega with one of her most telling character moments, when she reassures Bennie that it’s not worth fighting, she’s been through this before).

On Blu-ray, the film has a slightly ragged feel, the quality of the photography running from lyrically beautiful to murky and grainy, possibly a reflection of the low budget and the shooting conditions in rural Mexico. (There’s at least one sequence, the long emotionally fraught conversation between Bennie and Elita resting against a tree beside the road, where the disk image takes on a very peculiar quality; in many of the close-ups favouring Oates, the background has a strange texture which makes it look like a painted canvas backdrop.)

The Twilight Time disk has more supplements than usual for the company, including two commentary tracks, a lengthy interview featurette with Peckinpah biographer Garner Simmons (26:00) and a long documentary about the making of the film, with interviews from many of the people involved (55:36).

Comments

Dear Cagey Films,

I must say, your website is an absolute treasure trove of insightful film reviews and articles! I thoroughly enjoyed reading your analysis of the Twilight Time releases. Your attention to detail and deep understanding of the films truly impressed me. Your writing style is engaging and informative, making me want to explore these movies even further. Thank you for sharing such valuable content with film enthusiasts like myself. Keep up the excellent work!

Best regards,

Gary Ford