Criterion Blu-ray Review: Riot In Cell Block 11 (1954)

Violence runs through the films of Don Siegel, but so does ambiguity. In much of his work, characters become trapped in cycles of violence, with no one emerging as an uncompromised “good guy” (even Dirty Harry, despite the widely held critical opinion at the time of its release that it unquestioningly supported his brutality, is a mirror image of the serial killer Scorpio, the two of them locked in a cycle of violence which sets them both outside of society). This particular aspect of Siegel’s filmmaking was central to his breakout eighth feature, Riot In Cell Block 11 (1954). And yet Riot is quite unlike the rest of his work.

The project was initiated by producer Walter Wanger, a well-known Hollywood leftist, after he found himself serving time (admittedly in a minimum security prison) for shooting agent Jennings Lang, who was having an affair with Wanger’s wife, Joan Bennett. Riot In Cell Block 11 fits squarely into its period’s crusading docudrama mold, offering an expose of prison conditions at a time when frequent riots were breaking out in penitentiaries across the country. Wanger had writer Richard Collins base his script closely on a riot at the prison in Jackson, Michigan, in 1952, with many of the film’s characters modeled on the actual participants in that event.

Siegel was brought into the project when the script was almost ready and the backers wanted shooting to start pretty much right away. While finalizing the script, Siegel and Wanger scouted a number of prisons as possible locations, eventually settling on Folsom, where there was an empty 19th Century block which could house the production. Given the events depicted, it seems remarkable that the filmmakers received full cooperation from the prison administration – the lengthy sequence in which the riot spreads through the other blocks and out into the yard involves actual prisoners and guards in a large scale confrontation which was shot under the eyes of armed guards up on the walls who were prepared to take violent action if things got genuinely out of hand.

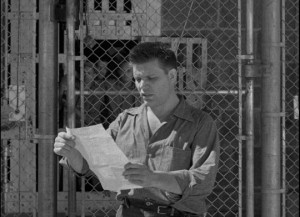

Shot by Russell Harlan (whose thirty-plus-year career included a remarkable range of projects – from Red River to The Thing to Pollyanna and To Kill a Mockingbird), Riot achieves a stark documentary look and tone. In fact, the images used to illustrate the booklet included with Criterion’s new dual-format edition look like genuine news photos. This is all helped by the lack of stars and the choice to go with minor and little-known actors. Neville Brand as James Dunn, the riot’s leader; Leo Gordon as Crazy Mike Carnie, his psychopathic right-hand man; Robert Osterloh as The Colonel, the reasonable counter-voice; Emile Meyer as Warden Reynolds and Frank Faylen as Commissioner Haskell, the closest the film has to a villain – against Reynolds’ urging for improved conditions in the prison, he advocates greater brutality and repression.

By the time Riot was made, the prison movie had been almost rigidly codified (in large part by Warner Brothers, starting in the early ’30s). What is most striking about Siegel’s film is the complete absence of all the standard tropes. There’s no wrongfully imprisoned hero; no sadistic warden; no desperate attempts to tunnel out or go over the wall; no loving girl waiting patiently on the outside. In fact, there’s a complete absence of melodrama altogether. Although the characters are strongly drawn, the film’s emphasis isn’t on individuals, but rather on the dysfunctional institution itself; with thousands of men jammed into cages with nothing to do (not even a prison machine shop or laundry to occupy their time), madness and violence are inevitable.

Sticking to its documentary intent, the film depicts the process of the riot from the moment it starts, through a series of escalating tensions to what, for a moment, appears to be a positive outcome before it plunges back into hopelessness. And within that process, Wanger, Collins and Siegel manage to create a remarkably nuanced portrait of the men involved, with conflicted motives, good intentions, fear and anger all playing a part.

Although the prisoners are not glossed over – Crazy Mike is a dangerous psychopath; another minor character is obviously a sexual predator stalking naive young cons; Dunn himself is brutal and possibly racist – we see that their demands are entirely justified and in fact echo the warden’s own pleas to the state for improved conditions. These men are driven by desperation and have no other way of calling attention to circumstances which not only fail to offer a chance of rehabilitation, but actually amplify and reinforce criminality. By the end of the film, the audience has been shown that the violence arises from a broken system which – more through laziness and disinterest than any genuine belief in harsh, inhumane punishment – has created a pressure cooker in which violent action is the only possible release.

Given the scale of the action in the film, it’s all the more remarkable that it was shot in just sixteen days, with so much care in getting the visual texture and performances so right. One interesting aspect of this fidelity to the real situation is the unremarked presence of blacks among both the prison population and the guards; even as late as 1954, this casual mixing of races was extremely rare in Hollywood.

The disk

Criterion’s Blu-ray derives from a 4K transfer from the original negative. Not surprisingly, given how quickly the film was shot, there’s some unevenness to the image, a few moments of soft focus, camera shadows in frame, and film grain (which has thankfully not been smoothed out by digital noise reduction). For the most part, the image has fine contrast and rich blacks, providing an appropriate noir feel to much of the action inside the cell block, while as previously mentioned the action out in the yard has a strong documentary feel. Criterion notes that the film was screened in both 1.37:1 and 1.85:1 ratios and they have chosen to present it in an open matte 1.37:1 format, which gives quite a bit of extra head and foot room; zooming the image in on an HD screen provides a more pleasing, focused widescreen picture.

The mono sound is strong, with clear dialogue and ambiances; the harsh sounds of prison doors and the echoing roar of the riot inside the block give a grim immediacy to the location.

The supplements

The disk offers a selection of audio-only supplements, starting with a detailed and informative commentary track by Matthew H. Bernstein, who fills in the production background – Wanger’s own prison experience as well as the Jackson prison riot – as well as details of the shoot itself.

Don Siegel’s son, Kristoffer Tabori, reads a chapter from Siegel’s autobiography, A Siegel Film, which recounts the production, and an excerpt from Stuart A Kaminsky’s Don Siegel: Director.

There’s also a fascinating NBC radio documentary from 1953 dealing with the Jackson, Michigan, riot; part of a series on prisons by reporters Peg and Walter McGraw, it includes interviews with many of the key participants, including Earl Ward, who was the model for Neville Brand’s James Dunn. Somewhat frustratingly, Criterion gives us only the first of two parts dedicated to Jackson; the hour-long program ends at a critical point in the riot.

The booklet accompanying the disk contains an essay by critic Chris Fujiwara; an article written by Wanger about his own impressions of what was wrong with the American penal system, published in Life shortly before the film’s release; and a brief piece by Sam Peckinpah about Siegel, who gave him his first job in film as a gofer on Riot In Cell Block 11.

The Criterion edition contains two disks, one Blu-ray and one DVD, with all content included on both.

Comments