When Horror Came to Shochiku: from absurd to apocalypse …

Dr Stein (Mike Daneen): Love demands courage.

Lisa (Peggy Neal): Yes, that’s the lesson Guilala taught me.

Finding myself off work for a day with some nasty kind of flu bug, by a strange coincidence the mailman knocked at my door and delivered the Criterion Eclipse set, When Horror Came to Shochiku. Given my pitiful physical state, slightly feverish and perhaps prone to hallucinatory moments, it seemed appropriate to curl up and watch all four movies in a row.

Shochiku, established in the ’20s, was one of the most prestigious of Japanese studios, home for his entire career to Ozu Yasujiro. Having focused on serious dramas, the studio came late to horror and science fiction, producing just four features in 1967-68. Studios like Toho (Godzilla, Mothra et al.) and Daiei (Gamera, Daimajin) throughout the ’50s and early ’60s had established strong traditions in these genres, but lacking that kind of foundation, Shochiku came up with four very different, and frequently deranged, movies.

On a technical level, these films were less well-executed than Toho’s – the opticals tend to be less polished, and the miniatures, although at times very elaborate, are typically shot over-lit, with no apparent attempt to disguise their scale. But for a true fan of Japanese genre films, these are not deal breakers. “Realism” is not a concern when dealing with dai-kaiju (giant monsters) … in fact, it’s the charm of guys in elaborate rubber suits stomping on miniature cityscapes that has kept Japanese monster movies popular for decades. One of the lessons so many CGI-happy filmmakers have failed to learn is that at times it’s the appeal of seeing the level of craft which has been invested in a fantasy film which matters more than a photo-realistic rendition of the “impossible” – the wonder of Willis O’Brien breathing life into his puppet Kong is so much more affecting than Peter Jackson’s tediously overblown digital ape.

The X From Outer Space (Kazui Nihonmatsu, 1967)

It might have been the sheer wacky awkwardness of Shochiku’s first attempt at a giant monster movie which made the studio go in different directions with their three subsequent efforts. Kazui Nihonmatsu’s The X From Outer Space is a strange, initially pretty tedious affair. The first half moves very slowly as a mission to Mars is set up and the crew members established. There’s a vague romantic triangle with space biologist Lisa (Peggy Neal) pining for Captain Sano (Shunya Wazaki), while he in turn longs for Michiko (Itoko Harada), stationed on the moon and for some reason giving him the cold shoulder. There are conflicts and comic relief of a pretty standard variety – a bit of weightlessness, the usual meteor swarm. And a peculiar UFO, supposedly the reason for all previous missions to Mars failing. This odd glowing object is ultimately never explained by the script, but as radioman Miyamoto (Shinichi Yanagisawa) says, it “looks like a half-cooked omelette.”

After a second attempt to make it to Mars, the crew discover some weird fungus-like objects clinging to the hull and Lisa insists on collecting a sample. Brought back to Earth, it’s left untended in the lab while everyone goes looking for a bar. But their evening out is interrupted by a massive explosion just over the hill … and here, at the halfway point, the movie finally comes to life.

The alien spore has quickly grown into Guilala, one of the most hilariously misconceived monsters in a genre often given to extremes. It has an odd, blade-shaped head which gives it a vague resemblance to a chicken with antennae (and what looks like a shower head sprouting from its forehead), huge padded shoulders like the worst costume Joan Crawford ever wore, a scaly hide, and the not unsurprising ability to spit fireballs. It also has a peculiarly distinctive gait somewhat reminiscent of a toddler which has just learned to balance on its feet and is now prone to rushing around, arms outstretched, partly for balance, partly to ward off a fall.

The rest of the film goes through the standard sequence of such stories: Guilala feeds on energy and trashes cities and industrial complexes as it makes its way towards the space service’s atomic stockpiles; Lisa is quickly working on a new material extracted from moon rocks which may afford protection from the beast; there’s a race against time to save Lisa from a collapsed building as the monster approaches, and a last minute attack with the “guilalanium”, a kind of whipped topping which smothers the creature.

The poorly structured script and often very lethargic pacing work against the movie, as does the inappropriate lounge music score, but the design of Guilala makes up for a lot, and it demands to be seen by any fan of dai-kaiju. The Eclipse disk offers an alternate English dub track in addition to the original Japanese and it’s pretty excruciating to listen to.

Goke, Body Snatcher From Hell (Sato Hajime, 1968)

The second of Shochiku’s four genre films is also the best. Moving away completely from rubber-suited monsters, Sato Hajime’s Goke is a bleak, apocalyptic fantasy about the end of the world as experienced by the crew and passengers of a crashed airliner. As the film opens, the plane is flying through a strange blood-red sky (referenced by Quentin Tarantino in Kill Bill); crows crash against the windows in bloody bird suicides; a report comes over the radio that there may be a bomb on board; and the plane is buzzed by a brightly glowing object which causes it to crash on a bleak mountaintop.

On board are a venal arms dealer who has openly prostituted his wife to a powerful, corrupt politician in hopes of scoring a big defence contract; an American woman on her way to collect the body of her husband who was killed in Vietnam; a chilly scientist; the young would-be bomber; the pilot and stewardess; and a mysterious man who turns out to be an assassin who recently killed the British ambassador. War and death hang over the film from the start (there are brief montages of newsreel footage from Vietnam) and the survivors of the crash bicker and argue in ways which work against their group survival. Definitely something wrong with the human species …

These deep flaws in our nature make us an ideal target for an alien race called the Gokemidoro who have decided to take the planet from us. The assassin, attempting to escape, is lured into the glowing UFO where a glistening parasitic blob splits open his forehead and oozes inside, turning him into a silent blood-drinking monster which starts to prey on the others as they seem to work hard at destroying each other.

Although the effects may seem rather crude now, the film’s visual design and its bleak, nihilistic tone give it a power which transcends budgetary and technical limitations. Of the four films, this one is the most visually striking and inventive, frequently reminiscent of Mario Bava’s intensely stylized used of colour (it would make a fine double bill with Bava’s Planet of the Vampires). The final sequence in which the last two survivors manage to make their way back out of the wilderness is a haunting vision of world’s end, making Goke one of the most poetically despairing Japanese fantasies since the original Gojira.

The Living Skeleton (Hiroshi Matsuno, 1968)

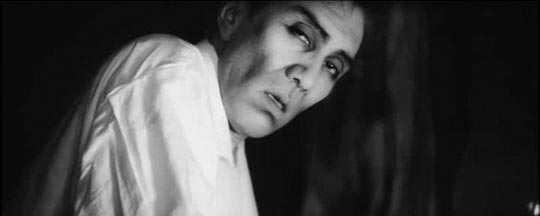

The studio changed gears again with its next horror film. The Living Skeleton, directed by Hiroshi Matsuno (who had been an assistant to Mikio Naruse among others and went on to a successful television career), ditches monsters and aliens altogether. The only one of the four films shot in black and white, it starts with a powerful and disturbing sequence in which some renegade crew members gather everyone on board a freighter on deck and massacre them with machine guns. Among the dead is Yoriko (Kikko Matsuoka), the young bride of the ship’s doctor.

With its coastal setting and death-haunted atmosphere, The Living Skeleton seems to belong to another Japanese tradition altogether, the ghost story. The main character is Saeko, the twin sister of Yoriko (also played by Matsuoka), who three years after her sister’s disappearance at sea lives with a priest (Masumi Okada) who has assumed the role of her protector. One day, out scuba diving with her boyfriend Mochizuki (Yasunori Irikawa), Saeko sees a line of skeletons on the sea bottom, held there by metal chains. Soon after, a ghostly ship appears on the horizon and she insists on taking a small boat out to it, despite the bad weather. When the boat capsizes, her boyfriend loses track of her and she ends up on the abandoned freighter by herself. Seeming to encounter Yoriko, Saeko passes out.

The movie then shifts its attention to the men who hijacked the ship – one now a wealthy club owner, another a drunk … and one by one they are driven to their deaths by encounters with what they believe to be the ghost of Yoriko. It’s here that the script, aiming for ambiguity, starts to become unclear. Saeko herself feels responsible for the men’s deaths; she confesses to the priest that Yoriko told her about being raped and murdered, and that her dead sister led her to the culprits; but there are also hints of Yoriko’s ghostly presence (appearing in a car’s rear-view mirror, on the rainy porch of Mochizuki’s bar), but whether Saeko is in some way possessed by Yoriko is left vague.

And then, eventually it seems that the freighter is not actually a ghost ship at all; that the doctor wasn’t actually killed, but is now mad and trying to revive his perfectly preserved dead bride by feeding her his own blood … or something … while filling his spare time by brewing the world’s most powerful acid for no clear reason. The final revelation of the lead pirate’s identity isn’t much of a surprise and by the end of the film, the script’s inability to decide just how much of the narrative is actually supernatural, how much merely psychological, has undermined a lot of the brooding atmosphere with which it started out.

What The Living Skeleton does share with Goke and the subsequent film, Genocide, is a bleak view of the human capacity for violence, though in this instance on a smaller, more personal scale. These Shochiku features have a grimness which Toho had long since left behind as that studio pursued ever wilder monster fantasies, often aimed at an audience of children.

Genocide (Kazui Nihonmatsu, 1968)

The final film of Shochiku’s brief flirtation with horror is another bleak contemplation of self-destructive violence as an essential human trait. Again directed by Nihonmatsu, Genocide is a vast improvement over The X From Outer Space; the director keeps the action of a very densely plotted script moving at a steady pace towards another apocalyptic climax.

Neglecting his wife Yukari (Emi Shindo), Joji (Yusuke Kawazu) goes on insect-hunting expeditions on a remote Pacific island, collecting samples to send back to a lab on the mainland. He also uses these trips to pursue an affair with caucasian Annabelle. As the couple lie on a beach making out, they see a plane high overhead. This turns out to be a US air force jet transporting a hydrogen bomb. As crewmember Charly (Chico Roland, the feverish GI on the run in Koreyoshi Kurahara’s Black Sun [1964]) flips out with a bad flashback to Vietnam, a swarm of insects attack the plane; the engines burst into flames and the plane goes down, the crew bailing, with the bomb dropping somewhere on the island.

What follows is a multi-faceted collection of interlocking plots involving arrogant US military personnel looking for the bomb, “eastern agents” also on the trail of the missing weapon, Joji accused of murdering the aircrew, a scientist from the mainland investigating strange deaths caused by new, highly toxic species of insect, Yukari being molested by her unsavoury boss at the local bar … and Annabelle (Kathy Horan) turning out to be something very different from what she first appears.

As in Goke, very explicit references to war (Vietnam and World War Two in particular), provide a background of human perfidy which motivates a bitter plot to put an end to all human life on Earth. The deadly insects are being bred by Annabelle to exact revenge for what she suffered as a child in a Nazi concentration camp, the bugs being willing allies in her plan because as an aggregate consciousness they’ve decided they don’t want to be wiped out along with the self-destructive human species. They may well be right as, even in the face of impending apocalypse, the various factions are more interested in getting hold of weapons and wiping each other out than they are in any kind of species solidarity.

*

Although this Shochiku quartet don’t represent the best of Japanese fantasy, there’s a sometimes disturbing intensity to them and a conceptual originality which make them all worthwhile viewing. The liner notes by Chuck Stephens oversell them somewhat and his tone is jokier than the films, for all their limitations, warrant. Apart from the ludicrous monster design in The X From Outer Space, none of the films deserve to be seen as camp and we owe Criterion a big thanks for putting them together in this attractive package.

Comments