Stanley Kubrick 4B: America in England

– Dr. Strangelove (1964)

By 1964, Stanley Kubrick had been honing his filmmaking skills for more than ten years in a series of increasingly ambitious projects, all of which were somewhat conventional in terms of form and content – film noir, historical epic, war film. Even Lolita, although the subject matter pushed accepted boundaries, is recognizable as melodrama. For his follow-up project, Kubrick settled on a thriller about an “accidental” nuclear war based on the novel Red Alert by British author Peter George (published under the pseudonym Peter Bryant). But something happened during the process of adaptation (Kubrick worked with the author and later Terry Southern) and what finally emerged was no longer a bleak serious-minded statement about nuclear danger. The resulting film, Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), was quite unlike anything seen before, a thriller laced with dark comic touches, elements of satire, a mix of rigorous visual realism and grotesque exaggerations, all of which seemed to require a new way of seeing and digesting what was up there on the screen. In short, Dr. Strangelove, finally, was the first truly Kubrickian movie, the first fully realized expression of his view of the world and human behaviour – and, as entertaining as it was, it made for decidedly uncomfortable, even disturbing viewing. In the shared U.S.-Soviet policy of MAD (Mutually Assured Destruction), Kubrick had found the perfect reflection of the self-destructive tendencies he saw at the heart of human experience.

Dr. Strangelove (1964)

While Lolita had presented America through a lens of sexual obsession, Kubrick’s second made-in-Britain project proposed a nation deranged to the point of madness by an obsession with “security” which, paradoxically, virtually ensured annihilation. As if this had cleared something out of his system, he didn’t return to an American setting again until 1980, with his adaptation of Stephen King’s The Shining.

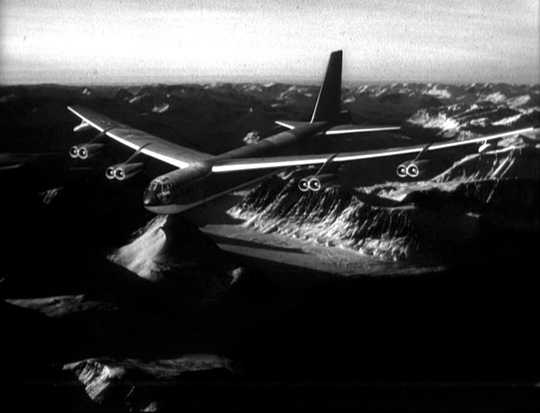

Aside from a handful of brief scenes, all of Dr. Strangelove takes place in three confined spaces: General Jack D. Ripper’s office at Burpleson Air Force Base, the War Room beneath the White House, and on one of the B-52s which General Ripper sends to attack Russia. In each of these places, different aspects of the situation are played out to their logical conclusions.

At Burpleson, General Ripper (Sterling Hayden) explains his motives to his RAF exchange executive officer, Group Captain Lionel Mandrake (Peter Sellers). Ripper holds a Soviet plot to contaminate “our precious bodily fluids” responsible for his own sexual impotence, launching the attack as a kind of surrogate orgasmic release.

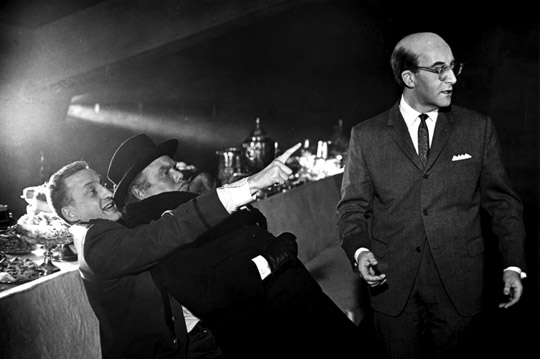

In the War Room, President Merkin Muffley (Sellers again) tries to use reason to resolve the situation, getting on the phone to the Russian premier to help the “enemy” destroy the U.S. planes, while verbally dueling with the rampant Air Force General Buck Turgidson (George C. Scott) who advocates following Ripper’s lead with an all-out attack – “I’m not saying we won’t get our hair mussed, but I am saying ten million, twenty million American casualties, tops.” (In front of Turgidson on the big War Room table is a briefing book titled “World Casualties in Mega-Deaths”. It’s this kind of pedantic technocratic detail – like the contents of the crew’s survival kits on the B-52 – which help to normalize the madness and make the unthinkable thinkable.)

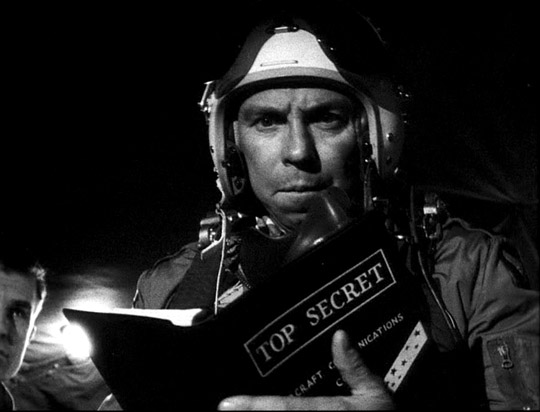

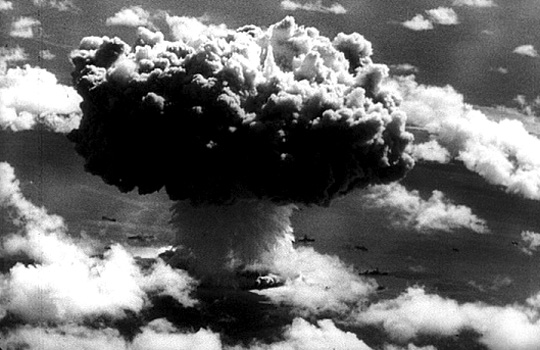

In Burpleson and the War Room, we see clearly the human fallibility which makes the nuclear deterrent so risky. On board the B-52 piloted by Texan Major “King” Kong, we see the technical proficiency supposedly designed to overcome such frailty. Kong and his crew, highly trained technicians, do everything in their power to carry out their mission once the orders are received and it’s difficult not to root for them as they evade Russian radar, compensate for serious damage caused by a close missile detonation, urgently revise their mission plans as they lose fuel and their designated target is no longer within range … the surrogate sexual act initiated by General Ripper reaches its climax with Major Kong riding the phallic bomb down to its target and the ensuing explosion provides orgasmic release from the narrative tension which Kubrick has sustained so skilfully throughout the film.

The coda in the War Room introduces the President’s deranged science adviser, Dr. Strangelove (Sellers yet again), a crippled ex(?)-Nazi who offers a solution in the “preservation of a nucleus of humanity” in deep mineshafts, where privileged men will be provided with multiple attractive females for the purpose of repopulating the post-war planet. The final image of Strangelove rising from his wheelchair and crying exultantly “Mein Fuhrer! I can walk!” leaves no doubt about the underlying politics of the whole MAD process, the triumph of twisted “supermen” through global genocide.

There’s no question that Dr. Strangelove is a very funny film, the comedy largely deriving from characters whose absurdity is merely an extension of recognizable real-world types. But beneath that comic overlay, Kubrick and his co-writers have dissected the political insanity on which the entire global system has been based – the sheer madness resulting from small, damaged, fallible human beings possessing a power far beyond their abilities to control.

The film was very popular on release and garnered multiple award nominations (including four for Oscars) and a number of wins. But the critical reception was uneasy. Bosley Crowther in the New York Times called it “beyond any question the most shattering sick joke I’ve ever come across”; after praising its brilliance and Kubrick’s technical skill, he concluded that “Somehow, to me, it isn’t funny. It is malefic and sick.” For Crowther, there was something unsavoury about the film’s lack of respect for authority: “I am troubled by the feeling, which runs all through the film, of discredit and even contempt for our whole defense establishment, up to and even including the hypothetical Commander in Chief” – obviously not wanting to see the film’s point that the “defense establishment” is the essence of the problem.

Pauline Kael, having praised Kubrick’s Lolita, was infuriated by Dr. Strangelove. She strangely accused it of “concealing its liberal pieties”, although the film makes it so clear that, in the face of the nuclear threat, all politics becomes ineffectual. She also tut-tutted that “A new generation enjoyed seeing the world as insane; they literally learned to stop worrying and love the bomb.” As if, somehow, the audience had found the spectacle of world destruction at the hands of a bunch of technocrats a desirable thing. What they (and we) laugh at, perhaps uneasily, is the spectacle of our own species so completely disconnected from its own best interests – and perhaps there’s a touch of relief that we ourselves, sitting in the audience, can see the world more clearly than those people in positions of power who have been trapped by their own schemes. The more plausible result of viewing the film is a sense of anger and a desire to put a stop to the madness, and of course Dr. Strangelove was released at the beginning of the massive social shifts which saw rising protest against the war in Vietnam, against the constrictions of complacent post-war politics and the social and economic constraints on gender, with the resulting breakdown of rules of personal and sexual behaviour.

But despite being so rooted in a particular historical moment, Dr. Strangelove remains one of Kubrick’s least-dated films. This has something to do with the narrative precision of the script, the brilliant performances which embody such well-drawn archetypes that they seem as fresh and relevant today as they did 48 years ago … but it also has something to do with Kubrick’s obsessive attention to design. Everything about the film feels authentic, from the vast War Room set (so impressive that Ronald Reagan asked to see the real thing as soon as he moved into the White House, no doubt disappointed to discover that it didn’t actually exist), to the newsreel-like assault on Burpleson Air Force Base, to the interior of the B-52. The latter was an invention based on one grainy photograph on a book cover, but the production was approached by military officials who wanted to know where they got hold of all that secret technology.

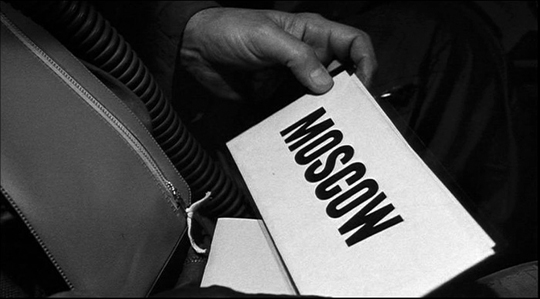

The scenes in the plane play to our love of machines and processes; there’s a sense of exhilaration in seeing the crew flipping their switches, checking their manuals, calculating fuel-loss rates and finding some way, any way, to complete their mission against all odds. This is the most disturbing aspect of the film, the realization of just how easily we as viewers can engage with these men and their mission, get caught up in the excitement and actually want them to succeed. One only needs to take a look at Sidney Lumet’s very dated Fail-Safe (also 1964) to appreciate Kubrick’s accomplishment here. Lumet (adapting the novel by Eugene Burdick and Harvey Wheeler) presents a whole lot of well-meaning, liberal-minded politicians and military men dealing with an accidental nuclear attack; a communications malfunction sends a bomber towards Russia – it’s a failure of the machinery, not the people involved in the system. But what really undermines Fail-Safe is the poverty of its design; the interior of the plane, while a bit more sophisticated than an Ed Wood set, looks like something thrown together in the corner of a studio; and when the crew receive their erroneous signal, the pilot opens an envelope and pulls out a large piece of cardboard with the word “Moscow” printed on it. This is at the level of a high school play in comparison with the complex and detailed manuals Major Kong and his crew have to consult to get the details of their “mission profile”.

My point is simply that, despite the comedy, despite the caricatures and archetypes, Kubrick instills Dr. Strangelove with an urgent sense of completely plausible technical reality which lays bare the madness underlying a system which for a time literally threatened the survival of everyone on the planet.

For me personally, the final montage of nuclear explosions evokes emotions completely outside of the film itself. Along with films like Atomic Cafe (1982) and Peter Kuran’s Trinity and Beyond (1995), with their seemingly endless footage of bomb “tests”, those final archival images in Dr. Strangelove serve to remind us that an appalling number of these devices have really been detonated on this planet by a relatively small number of cool, rational technocrats. By people whose narrow technical focus has made them susceptible to being swept up by the momentum of the technology they’ve developed without serious regard for the virtually inevitable consequences of their work.

Comments