Flipside: extreme male anxiety

The latest pair of releases from the BFI’s Flipside series offer a fascinating snapshot of what was happening to the male sense of identity at the height of the feminist impact on filmmaking in the ’70s and early ’80s. While people like Sally Potter, Lizzie Borden and Marleen Gorris were dissecting and reformulating the ways in which women were depicted in popular culture, there was a growing sense of masculinity under siege. One response was an eruption of testosterone-fuelled action movies (which are still with us); another was the surfacing of a kind of frenzied sexual anxiety. The BFI offers up three samples of the latter on these two releases.

Repeater (1979) and Voice Over (1981)

Chris Monger, an art student from Cardiff, approached film somewhat like his feminist contemporaries, from a theoretical and formalist angle. His two early features, Repeater (1979) and Voice Over (1981), show the influence of the French New Wave (particularly Jean-Luc Godard) and the deconstructionism which was in sway in academia at the time. The less successful Repeater tells the story of Marie (Chris Abrahams), a woman who walks into a police station to confess to the murder of her crippled lover. The police dismiss the confession, ruling the death suicide – somewhat implausibly as the drugged, paralysed man could hardly have shot himself. This point highlights the film’s biggest weakness: more concerned with playing narrative games, Monger makes no attempt to ground the film in any kind of narrative reality.

While Marie is at the police station, in an adjacent room a suspected hitman named Dieter (John Cassady) is being interrogated. With no evidence to hold him, he’s released at the same time as Marie and they meet in the street outside. Her guilt drives her to hire Dieter to kill her (she creates a “twin” of herself to be the target), but it turns out that he’s not really a hitman, merely the front for an older woman who actually does the killing. When Dieter fails to fulfil the contract, Marie shoots him and returns to the police station to confess again to murder.

Throughout Repeater, Monger is playing with camera and editing techniques, making visual references to the New Wave, using camera movement and tableau staging to create the feeling of a three-dimensional painting … all of which creates a distance, a disengagement from the characters and events being depicted. Although it’s concerned with a woman who kills weak, inadequate men, it’s not until Monger’s next feature, Voice Over, that questions of male adequacy become the central focus.

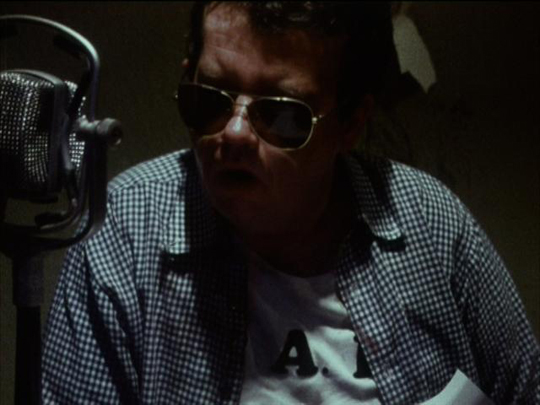

Voice Over stars Ian McNeice as Fats Bannerman, the writer of a hugely popular radio drama called Thus Engaged, which is closer to Harlequin Romance than to the Jane Austen it attempts to evoke. Here, as in Repeater, Monger isn’t particularly concerned with narrative plausibility. Although the film is shot in some impressively gritty locations in Cardiff, it’s difficult to imagine Bannerman’s chaste Regency romance (which is simply read by him on air) being a huge hit, even an ironic one. And yet the film presents him as a kind of media star, lauded by hangers-on and presented with industry awards.

Admittedly, when he’s interviewed by a somewhat aggressive female reporter after winning one of those awards, he’s informed that the majority of his audience only listen in order to laugh at his sexless romantic fantasies. And later, when he’s picked up by a couple of his fans at a bar and taken back to their flat falling-down drunk, they mock and humiliate him for his absurdity.

One night, he finds one of those fans beaten senseless in an alley (possibly raped) and takes her home. For some reason, the doctor he calls in makes no effort to notify the authorities, but instead allows Fats to keep her. Unable to speak, in a semi-catatonic state, she lingers in his bleak flat and his radio show begins to change as he attempts to use it to communicate with her. As he adds sex and horror to the mix, his ratings grow and he’s lured away to a bigger radio station … but the woman’s continuing silence drives Fats into ever more twisted fantasies, until he finally acts out a violent conclusion to the “relationship”.

Voice Over delineates an attempt to define gender relations and sexuality from the man’s point of view, the woman essentially an object onto which Fats projects increasingly deranged fantasies. When it was shown at the Edinburgh Festival, feminists protested and Monger was attacked as a misogynist. The criticisms are understandable, if not entirely justifiable. The film is a quite powerful depiction of masculine pathology, but that doesn’t mean it endorses Fats … in fact, it presents Fats’ progress as an inexorable descent into madness. But at the same time, it does completely exclude the female voice (literally), an omission feminists took offence at because almost by definition they saw that absence already in every facet of the dominant culture.

This is the very issue that filmmakers like Sally Potter and Marleen Gorris were raising in their own work, but they approached it from the woman’s point of view. In Potter’s Thriller (1979), La Boheme‘s Mimi becomes aware that she is the intended victim in a male-devised plot to kill her for the sentimental satisfaction of an audience of men. In Gorris’ De stilte rond Christine M (1982), a woman on trial for murdering her husband refuses to speak in her own defence because the male-defined language of the legal process is incapable of encompassing the woman’s experience. In Monger’s film, the woman’s voice is taken from her; in Gorris’, the woman’s voice is voluntarily withheld as a form of protest. As effective as Voice Over is as an analysis of the limitations and deformations of Fats’ view of women, the film can’t help but repeat those limitations to some degree in its form. Still, as problematic as it is, it remains fascinating because of the intensity of McNeice’s performance.

Little Malcolm & His Struggle Against the Eunuchs (1974)

While Monger’s films have a rough, guerrilla feel, Stuart Cooper’s Little Malcolm and His Struggle Against the Eunuchs (1974) is a very polished piece of work, photographed by the great John Alcott between A Clockwork Orange (1971) and Barry Lyndon (1975). The only other work by Cooper that I’ve seen is the Criterion edition of the disappointing Overlord (1975). Also shot by Alcott, that film combined remarkable documentary footage culled from the Imperial War Museum’s collection with a trite, unimaginative story about a young soldier waiting to embark on the D-Day landings in 1944.

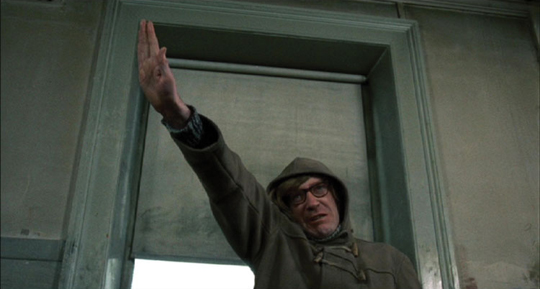

Little Malcolm, however, is original, entertaining and powerful. Based on a play by David Halliwell, it stars John Hurt as Scrawdyke, recently expelled from art school for vague reasons. With his cronies Wick (John McEnery), Irwin (Raymond Platt) and the barely tolerated Nipple (David Warner), Scrawdyke forms his own political movement, the Party of Dynamic Erection, and formulates a plan to humiliate and destroy the professor who got him kicked out of school, the never-seen Philip Allard. I’ve seen some criticism that the actors are all too old for their art student roles, but actually that works to the film’s advantage, emphasizing the arrested development underlying their view of the world.

The subject and substance of Little Malcolm is impotence and the fury that arises from it. Malcolm is paralysed by the presence of women, holding them in contempt because they remind him of his weakness, while Nipple provides a lengthy monologue about his own supposed prowess which garners nothing but derisive ridicule from his fellow rebels.

The four act out their plan to kidnap Allard in a lengthy sequence of slapstick incompetence, their fantasies of revenge obviously outside any possibility of realization. As if to compensate, the group’s plans become more grandiose … there’s a terrific “rally” in the snow at which Malcolm spouts out his political philosophy, plunging headlong into fascism. Nipple is put on trial for vague reasons by the other three, his only options to plead either “guilty” or “very guilty” before being condemned to death and driven irrevocably from the fold.

Little Malcolm is an incisive dissection of the sexual roots of a certain kind of political behaviour, packed with verbal and visual wit. But where it really trumps Monger’s work is in its incorporation of an observant woman into the mix, refining the critique to devastating effect.

Anne Gedge (Rosalind Ayres), a young student who’s attracted to Malcolm, invites the revolutionary home for a cup of tea only to see him flee in terror. Later she shows up at his flat to confront him, offering herself sexually and using the offer to expose the impotence which is driving his rebellion. Just as she’s reached the point where he has no choice but to admit his own weakness, his partners arrive and their presence gives him the will to fight back, the physical power of the group able to intimidate her where his weak excuses have failed. The woman’s voice, speaking the truth that Malcolm can’t bear to hear, has to be silenced and the three of them attack Anne. When the outburst is over, they’re stunned to (mistakenly) think that they’ve killed her.

The chilling conclusion has Wick and Irwin demanding that Malcolm continue with their original plot against Allard, but by this point Malcolm is unable to act at all, his will broken, exposed as the pathetic failure he’s actually always been.

Little Malcolm and His Struggle Against the Eunuchs never feels constrained by its stage origins, Alcott’s camera capturing the action with great dynamism. But it’s definitely a very verbal work, the dialogue agile and witty, and the performances uniformly excellent. In fact, John Hurt has probably never been better, while David Warner turns in a hilarious portrait of self-delusion. And yet, in the end, it’s Rosalind Ayres as Anne who seems to dominate the film and provides it with a clear perspective.

Comments