Damnation and the Fields of Ambrosia

Nostalgia can be an odd thing.

As I’ve been working on my documentary about the history of movie-going in Winnipeg, and thinking about how much time I spent in the old theatres which no longer exist, and what it felt like to sit down in the dark to see something I’d heard or read about and had waited for, sometimes for months, even years (movies weren’t released in thousands of theatres on the same day back then, but spread more slowly, preceded by publicity and rumours), I occasionally find myself getting the urge to watch something I first saw many years ago, even though I know that I thought it was crap at the time.

Although Damnation Alley (1977) was based on a novel by a major science fiction writer (Roger Zelazny), had a script written by Lukas Heller (Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, Hush, Hush, Sweet Charlotte, Flight of the Phoenix and others) and polished by Alan Sharp (The Hired Hand, Ulzana’s Raid, Night Moves, etc) and was released five months after Star Wars, it’s an amazingly shoddy piece of work. Script, direction, special effects … everything about this movie is sub-par.

The original novel is about a convicted killer assigned to carry urgently needed vaccines across post-apocalyptic America, a place divided among multiple police states and ravaged by nightmarish storms many years after a nuclear war. Ideally, the movie should have been made on a low budget with William Smith starring as the renegade anti-hero Hell Tanner … it would have been a worthy follow-up for L.Q. Jones after A Boy and His Dog (1975). But instead, it struggled to be a major studio release (from 20th Century Fox – yes, the same studio that released Star Wars, and with a budget reputedly $4-million more than Lucas’s space opera).

The novel may have been a potboiler with a minimal road story/action plot, but the movie lacks even the simple MacGuffin of the vaccine and the pressure of the deadline to get it to plague-ridden Boston. But worse, Heller and Sharp transform the biker anti-hero into a small group of military men … and even worse than that, two of the men – Tanner (Jan-Michael Vincent) and Major Denton (George Peppard) – actually pushed the buttons to launch some of the missiles which wiped out most of the life on Earth and shifted the planet off its axis, causing the violent storms. At no point does the movie pause to examine that fact; we see these men unleash the holocaust in the first few minutes, then we’re expected to root for them for the rest of the movie. (I’m reminded of the fact that The Omega Man [1971] transforms Neville from an ordinary everyman into a military doctor who was involved in the biological weapons research which unleashed the vampiric plague which, yes, wiped out the world’s population – and once again, we were expected to root for him as the hero. And Hollywood’s always getting knocked for being too liberal!)

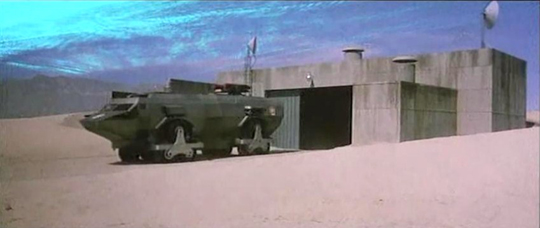

The problems with the script of Damnation Alley don’t stop there. When, after years of sitting around their desert missile base, our heroes finally decide to hit the road (after an explosion kills most of the personnel), Denton suddenly drives out of a big garage in a massive vehicle called the Landmaster. Tanner and his buddy Keegan (Paul Winfield) have never seen or heard of this before. Its origins are confusing, as an earlier scene seems to imply that Denton and his buddy Lt. Perry (Kip Niven) have been building something in there by hand – which would seem to be ridiculous. But then later, Denton says in passing that Tanner hadn’t known about it because it was “secret”. Hard to believe that something that big could remain hidden for years in one of just a few buildings on a small base in the desert.

Once on the road, we never actually see them finding gas to refuel (though we do see them not finding gas a couple of times), yet the behemoth keeps on running. It gets to Las Vegas where, somehow, all the power is still on though the city is buried under sand (in fact, everywhere they go, there are no signs of physical damage, just an absence of people … guess the Russians were using those special bombs that don’t harm buildings but turn people to ash). Here they find a glamorous woman, wannabe showgirl Janice (Dominique Sanda! – seven years after her impressive appearance in Bertolucci’s The Conformist [1970], and just a year after being in his 1900 [1976]; how did she end up here?), who joins them as they continue East, heading for Albany because there used to be a radio signal from there. In Salt Lake City, giant flesh-eating cockroaches get hold of Keegan – which gives occasion for the script’s most memorable line as Denton gets on the radio to Tanner and urgently warns that “the whole town is infested with killer cockroaches”. Later, at a remote desert cabin, they find Billy, a near-feral boy (Jackie Earle Haley, many years before his Rorschach turned out to be the best thing in Watchmen [2009]), who also joins the almost-nuclear family group.

After a run-in with a regulation group of cannibal hillbillies, a cataclysm strikes (much stock footage from old disaster movies), the Earth returns to its proper axis, the sun comes out and the desert has somehow miraculously reverted to forest and grassland. And just over the hill is “Albany”, which the whole disaster has changed from a city in New York State to a small California town.

While the narrative, such as it is, is a complete mess, it’s the sheer wretchedness of the technical aspects of Damnation Alley which sink it beyond redemption. From the early sequence of Tanner riding his dirt bike over dunes crawling with badly superimposed “giant” scorpions, to the endlessly amateurish, poorly matted opticals of the strange sky and the tornado forests and electrical storms – this movie looks worse than your average B-movie from the ’50s. If it really did have a bigger budget than Star Wars, the shoddiness of everything except the big vehicle itself is unforgivable.

Which brings us to the director, Jack Smight. After years of working in television, Smight moved to the big screen in the mid-’60s, most notably with Harper (1966), an adaptation (scripted by William Goldman) of a Ross Macdonald Lew Archer mystery, with Paul Newman as the renamed detective, Lew Harper. Two years later, Smight did well with another Goldman script, No Way To Treat a Lady (1968), in which Rod Steiger acted up a storm as a serial killer. The next year, he came out with a pedestrian Ray Bradbury adaptation, The Illustrated Man (1969), again starring Rod Steiger. By the early ’70s, he had returned to television, occasionally coming out with another feature during the decade – Airport 1975 (1974 – “the stewardess is flying the plane!”) and Damnation Alley most notable among them. All in all, not a particularly interesting career.

So I was surprised to discover his 1970 feature The Traveling Executioner (he both produced and directed), which has just been released by Warner Archive. This is a movie which could only have been made in those few years between Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and Jaws (1975), when American film broke free of studio restrictions and shot off in numerous unexpected directions before the big media corporations took control.

Beautifully designed by Edward Carfagno and George W. Davis, richly photographed by Philip Lathrop, and graced with a superb cast headed by Stacy Keach and Marianna Hill, this is a strangely romantic black comedy about a man named Jonas Candide (Keach, doing the finest work of his career, perhaps equaled only by Fat City [1972]) who travels around the South in the years of World War I in a carnival-coloured truck with an electric chair in the back. He goes from prison to prison performing executions, charming his “customers” with his vision of the Fields of Ambrosia, the paradise to which he’s sending them – they die calmly, with smiles on their faces.

Trouble is, on this particular day, he’s faced with his first female customer, a German woman named Gundred (Hill), and he finds his own calm certainty thrown into confusion. He finds ways to delay the execution, looks for a way to fake her death and spirit her away, and she plays him for all she’s worth. The story (written by Garrie Bateson – IMDb lists only three credits, this plus an episode each of Mission: Impossible and Night Gallery) runs inexorably full circle, with Candide finally offering the consolatory vision of the Fields of Ambrosia to the witnesses at his own execution.

Nowhere else in Smight’s work (most definitely including Damnation Alley) is there this sense of lightness, grace and poetry. You have to wonder what took hold of him for that brief moment exactly halfway through his career and just that once gifted him with genuine artistry.

Comments

Rather than reading the Archer stories solely as mysteries, thrillers, entertainments, and detective stories (though of course they can exist solely on that level for readers who are interested in them as such), we’d do ourselves a favor to consider them in a few other ways as well. In the massive reference work World Authors 1950-1970, published by the H.H. Wilson Company, Macdonald wrote that The Galton Case and Black Money “are probably my most complete renderings of the themes of smothered allegiance and uncertain identity which my work inherited from my early years.” Of course, in Black Money the smothered allegiance occurs between the lovers Ginny Fablon and Tappinger.

http://postmoderndeconstructionmadhouse.blogspot.com/2014/12/ross-macdonald-black-money.html#.VJYXdsAFB