Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985): Criterion Blu-ray review

The tension between creativity and commerce has run through more than a century of cinema history, particularly since the industrial model of production took hold (especially in Hollywood) in the late teens and ’20s. The more it cost to make movies, the more those who provided the funds wanted to control the “product” to maximize profit. While the most successful filmmakers in those early days managed to maintain a high degree of control over their work – the stars who formed United Artists in 1919 (Charlie Chaplin, D.W. Griffith, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks), creators like Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd – others were beholden to their financial backers and were expected to make movies tailored for the widest possible audience. The conflict was rooted in differences about just what would appeal to the masses.

While compromise was built into the production process, there have been many high-profile instances of ambitious filmmakers running afoul of corporate pressure. Either forced to change their work to accommodate front office demands or, in more extreme cases, having their films taken away and re-cut against their wishes, the results almost inevitably meant the defeat of art by commerce … although, ironically, the decisions of the supposedly more savvy businessmen often proved commercially unsuccessful and it would have been better for posterity simply to leave the filmmakers alone. Erich von Stroheim’s absurdly ambitious Greed (1924) in its original cut was an unlikely ten hours, but no matter how much he cut it down MGM wasn’t satisfied and the company finally took it away from him; cobbled together from various scenes with title cards struggling to maintain continuity, the resulting 140-minute cut, disowned by von Stroheim, was a commercial failure and the director’s own version was lost to history.

Almost as famous was the fate of Orson Welles’ second feature, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), taken away from the filmmaker by RKO executives who, after having given Welles carte blanche on his first feature, Citizen Kane (1941), had lost faith in the wunderkind when that film, despite critical accolades, had proved a commercial disappointment. While Welles was in Brazil working on It’s All True, the studio drastically cut the film by more than forty minutes and had editor Robert Wise shoot a new, more “positive” ending. Again, having severely damaged the filmmaker’s creative conception, the studio found their version to be another commercial disappointment; this began Welles’ move towards a peripatetic independence, which saw him struggle with a few more studio backed productions before heading to Europe, where he strove to maintain creative independence.

But even for Welles the prospect of studio financing drew him back to Hollywood in 1958 when producer Albert Zugsmith hired him to write, direct and star in Touch of Evil, only to face the familiar conflicts once again as the studio took the film away and re-cut it against Welles’ wishes. In this case, despite the results compromising the director’s intentions, the studio version was a modest commercial success. In 1976, a variant preview cut surfaced, which went some way towards restoring Welles’ intentions, but it was only in the late ’90s that a serious effort was made to reconstruct the film, with producer Rick Schmidlin and editor Walter Murch using all available material and following Welles’ famous 58-page memo to the studio with detailed notes on how best to edit the material he had shot. This was a revelation and an exemplary demonstration of the value of deferring to a talented filmmaker and trusting their creative decisions. While the studio version retained the broad narrative strokes of Welles’ film, the tone, pace and rhythm of the restored version instill the same material with so much more emotional and dramatic depth that, in retrospect, it’s impossible to see how the studio could have thought they were improving the film with their interference.

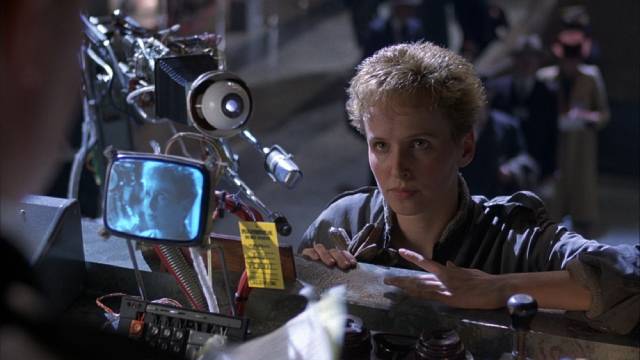

Ironically, that studio – Universal-International – found itself embroiled in a much more public version of this kind of dispute a quarter-century later when they financed a new film by another filmmaker, perhaps as headstrong and idiosyncratic as Welles himself. Terry Gilliam had emerged as a creative visual stylist with his cut-out animations for Monty Python’s Flying Circus (1969-74), and as co-director (with Terry Jones) of Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), and director of Jabberwocky (1977) and Time Bandits (1981). None of this work could be considered conventional; apart from the very skewed humour, all these projects foregrounded visual world-building with an obsessive attention to detail and texture. Holy Grail and Jabberwocky, for all their absurd off-the-wall humour, are two of the most convincing depictions of the Medieval world in all its muddy and bloody glory. Embedded in their rich visual fabric is a frequently very dark and cynical view of the world and the contingency of human existence.

This mix of humour and grim reality is integral to Gilliam’s work, even in the kids’ film Time Bandits, which infuses its boy’s own adventure with a surprising amount of anxiety and emotional pain (something which became even deeper and more disturbing in the underrated Tideland [2005]). What seems to have caused problems with the studio executives in the case of Brazil (1985) was an inability to understand that in Gilliam’s work narrative emerges from the intricately textured worlds he builds; story isn’t foregrounded, with setting mere decoration – meaning is inextricably embedded in design, with characters’ psychology and emotions shaped by the visual context in which they exist. So when the executives decided that Brazil’s narrative was too difficult and complicated for an American audience to understand, their efforts to “simplify” it were doomed to failure. Their attitude was a back-handed comment on the supposed lack of sophistication of that American audience; already released in Europe in Gilliam’s cut, the film was both commercially and critically successful, so the idea that it was beyond American comprehension reflected a rather low opinion of American viewers.

The difficulty of simplifying the narrative is largely due to the nature of the surface story itself. A superficial reading of protagonist Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce) seems to position him as a hero, an insignificant cog in the machinery of a totalitarian state who is spurred by circumstance to rise up and oppose an oppressive system. His actions ultimately fail, but it’s a noble effort while it lasts. Yet it’s not that simple, because his actions are taken in a very particular context which constantly calls them into question.

A lowly functionary in the Department of Records, he has no ambition to rise in the hierarchy despite the efforts of his socially well-connected mother (Katherine Helmond). In contrast with the dull routine of his job, he has an active imaginary life in which he is a heroic figure capable of flight, who opposes the forces of darkness as he fights to rescue the woman he loves. When a clerical error in the Department of Information Retrieval leads him to a housing project to deliver a refund cheque to the widow of an innocent man who has died under torture, he discovers that his fantasy woman lives in the same block and the two sides of his life begin to overlap.

But to comprehend what follows requires an understanding of the film’s world and how this setting has shaped him and, more importantly, how it has completely distorted his perception of the events he finds himself engaged in. Brazil presents a vision of a totalitarian dystopia in which the crushing weight of state bureaucracy combines with monumental incompetence to cause endemic dysfunction. The government justifies its efforts to control every aspect of life as necessary to counter the forces of a revolutionary terrorist organization whose existence seems confirmed by frequent bombings in the city. The whole security apparatus is built to fight against these terrorists … and yet, we never actually see signs of the organization; there’s the lowly worker Buttle (Brian Miller), whose arrest and death are the result of a clerical error, the flamboyant Tuttle (Robert De Niro), a freelance air conditioning repair man who works outside Central Services because he hates the paperwork but loves the game, and Jill Layton (Kim Greist), the object of Sam’s obsession, who dares to file a complaint about Buttle’s wrongful arrest. These are the bureaucracy’s targets, designated terrorists by default.

What seems more likely is that the ubiquitous explosions are actually just a function of the massively defective infrastructure of the city which is a maze of aging ducts and malfunctioning heating and cooling systems. That is, the government has invented the existence of a terrorist opposition in order to avoid fixing real problems and to justify their oppression of the population. But Sam himself is a part of the system and doesn’t question the reality of the official story, which in turn influences what he believes about Jill; he “loves” her because she resembles the woman of his dreams, but he can’t help but believe that she is in fact part of the terrorist group – so his feelings draw him inexorably into opposition to the state he has until now faithfully served. The darkest element of Brazil arises from Sam’s shift from his original heroic fantasy to real actions intended to “save” Jill, actions which essentially transform Sam into the only real terrorist in this world. Not only does he cause death and destruction among the security forces pursuing him and Jill, he’s ultimately responsible for her death too. In the end, facing torture himself at the hands of his former friend Jack Lint (Michael Palin), he retreats into another alternate fantasy, one in which he is no longer the hero but rather the character in need of rescue, saved if only momentarily by the heroic Tuttle and Jill.

It’s no doubt understandable that the Universal executives were concerned that the film, despite its visual invention and humour, is ultimately a downer – though it shouldn’t have been a surprise; even Time Bandits ends on a very bleak note, and that’s a kids’ film – but their attempts to “save” it were utterly misguided. Luckily we actually have the studio version for comparison, the so-called “Love Conquers All” cut, and it’s a remarkable object lesson in the futility of trying to transform material shot with one very clear, specific purpose into its diametric opposite. Cut by almost fifty minutes, rearranged and using alternate takes with different staging and dialogue, Universal’s cut is so much more confusing than Gilliam’s that it’s impossible to see how anyone could have thought they were doing something useful.

The main aim of this cut is to salvage Sam as the heroic, romantic protagonist he was in his own mind in Gilliam’s version, a figure which everything in the original version contradicted and undercut. In order to accomplish this, the studio’s editors stripped away vast amounts of the detail which created the film’s world, trying to relegate the film’s actual raison d’etre to mere background. If that wasn’t bad enough, they also had to truncate many scenes to remove material which undercut their conception of the character, rendering many moments incomprehensible. Having stripped out most of Sam’s fantasies, his fixation on Jill once he meets her has no dramatic grounding … in fact, nothing that happens has any dramatic grounding because there’s no understanding of the film’s world and thus no specificity to the characters’ actions. The original conception of Sam rests on a layering of perception, his self-image with its fantasy heroism versus the reality in which through his inability to understand the world he becomes a dangerously destructive, and ultimately self-destructive, force; with every bad decision, what initially seems charming becomes increasingly unlikable. And yet the studio cut tries to make him a uni-dimensional hero. This effort was doomed to fail simply because it wasn’t in the script and certainly wasn’t there in what Gilliam shot on set.

*

Despite the studio’s dislike of the film, their dispute with Gilliam hinged on running time.[1] The contract specified 125-minutes, but his cut was 142. With a lot of back-and-forth, he trimmed it down to 131-minutes, but the studio wouldn’t budge and when he refused to do any more cutting, they took it away and not only shortened it but tried to turn it into their idea of a cheerful, audience-friendly movie. (Ironically, the studio’s editors would call Gilliam to discuss their cut and were appalled that he wouldn’t talk to them, seeing this as a sign that he simply didn’t care about his own work.) As Gilliam’s version had been playing in Europe since February, there was no danger that his film would disappear completely, but there was a good chance that it would never be seen in a U.S. theatre. Given that this was long before the Internet and still fairly early in home video, this meant the loss of a potentially significant audience. More importantly, Gilliam saw tampering and possible suppression as a slap in the face of his creativity. And so he launched a campaign against the studio, which had changed management since the project was initially green-lit.

Audaciously, and at the risk of scuttling any future prospects in Hollywood, he took out a full-page ad in Variety asking when studio head Sid Sheinberg was going to release the film and also arranged a number of unauthorized, clandestine screenings of his cut. This led to the unprecedented step of the Los Angeles Film Critics Association awarding the film – unreleased, and possibly never to be released – Best Film, Best Director and Best Screenplay of the year. The very public dispute, combined with a groundswell of critical praise, eventually made Universal back down and they released the 131-minute cut theatrically. While this was a win for Gilliam, the executives no doubt felt vindicated when the box office take didn’t even cover production costs, though obviously its stature has only increased in time and Brazil now stands as Gilliam’s masterpiece.

*

The disks

Given the density of detail in the film’s imagery, with such elaborate production design and a wide range of in-camera effects, it’s no surprise that Brazil benefits from Criterion’s new 4K restoration. It is a bit disappointing for those who haven’t adopted the format yet that the Blu-ray included in the three-disk dual-format set hasn’t been remastered from the 4K, but simply duplicates the company’s original Blu-ray from 2012, which is decent but definitely below the standard of the new scan. The equally dense stereo soundtrack adds depth and texture to the film’s oppressive world.

The supplements

The set includes all the extras from Criterion’s previous editions – the 1996 laserdisk, the three-disk DVD set from 1999, and the 2012 two-disk Blu-ray set. In addition to Terry Gilliam’s 1996 commentary on both the 4K and Blu-ray disks, a second Blu-ray disk contains almost four-and-a-half hours of archival material which recounts the story of the film’s production as well as the controversy surrounding its release.

Rob Hedden’s What is Brazil? (29:07) details the production through interviews with Gilliam and members of the cast and crew, while the six-part Production Notebook (79:11) covers the development of the script, multiple dream sequences which were either dropped or didn’t get past the storyboard stage, production and costume design, special effects, and Michael Kamen’s score. The Battle of Brazil: A Video History (55:09), based on Jack Matthews’ excellent 1987 book The Battle of Brazil, recounts Gilliam’s fight with Universal to release his version of the film. And finally, as painful as it is to watch, Universal’s “Love Conquers All” cut (1:33:44), which was released only on syndicated television, is an invaluable glimpse of what Gilliam was fighting against.

There’s also a trailer (2:36) and a reprint of critic David Sterritt’s essay from the 2012 release.

________________________

(1.) This was also the rationale for the butchery of David Lynch’s Dune the previous year, once again at the insistence of Universal – the stipulation of rigidly fixed running times, regardless of the internal dictates of the material, seems long-since to have fallen by the way as distribution is no longer primarily theatrical and the old rule that movies had to be short enough to squeeze in one more show per day doesn’t apply now. It’s frustrating today to hear executives who oversaw the treatment of Dune say that it would’ve been better just to let Lynch finish the film as he wanted because cutting it down didn’t actually make it any more commercial. (return)

Comments