Lars Von Trier’s Europe Trilogy (1984-1991): Criterion Blu-ray review

Lars von Trier has never been a filmmaker for all tastes. From the start, his movies have provoked intense, conflicted reactions from audiences and critics. His publicly cultivated persona has been just as provocative, eliciting outrage at festivals with often offensive remarks which themselves are rooted in a history of anxiety and depression. If it seems that he has continually sought to offend, it is undeniable that he is a provocateur who possesses a remarkable depth of cinematic knowledge, though that knowledge is not contained within some kind of reverence for his forebears. One of the things which triggers negative criticism of his work is the impression that it’s steeped in mockery, both of cinema and of history itself. And yet reality and imagination are so entangled in his films that one of their primary effects is to force the audience to engage with and question long-held notions – of art, philosophy, politics, entertainment …

All of this was apparent from the start, seemingly erupting fully formed in his first feature – and even before that, in his film school projects. Perhaps his certainty, the confidence displayed in that early work, is itself intimidating, almost monstrous. His work from the beginning has been complex, allusive and in a way hermetically sealed in its own intense, disturbing and self-contained universe. For some, this is off-putting, stifling, arrogant. For others (myself included), his films are rich and immersive – in a way analogous to those of David Lynch. They possess a sense of danger, the risk of losing oneself in the artist’s imaginative reworking of our shared world.

Von Trier’s films display an intense, confrontational degree of artifice, their narratives almost buried in foregrounded aesthetic play. There’s a deep tension between that play and the darkness of the material itself, but the darkness doesn’t mitigate the play nor the play dissipate the darkness. There’s a sense in which the world as seen by von Trier is suspended perpetually between irresolvable opposites, leaving viewers in an uncomfortable state where they have to find their own accommodations with all the contradictions. There are no comfortable answers in von Trier’s cinematic universe.

In his first three features – loosely connected as the Europe Trilogy – he uses hypnosis as a device to draw both viewers and characters into an imaginary continent scarred by history (specifically the Second World War, Fascism, the Holocaust). This device obviously suggests a connection between hypnosis and our relationship to film-viewing itself, the trance-like experience of sitting in the dark and watching the flow of images on the screen; but it also implies that we are ourselves subject to forces outside ourselves, that like the films’ protagonists we suffer from an illusion of agency which may lead us to disaster as historical forces beyond our control shape our lives in unwanted ways.

Element of Crime (1984)

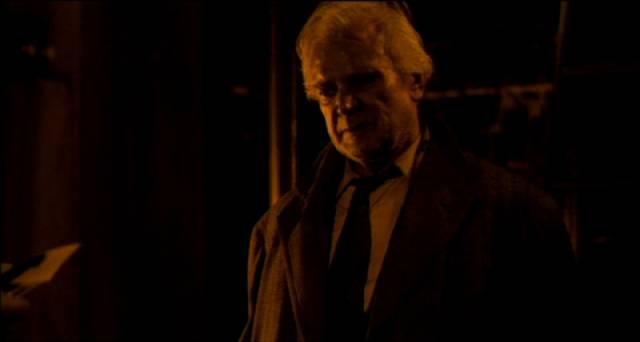

Von Trier’s first feature, Element of Crime (1984), begins in Cairo where the as-yet-unseen protagonist Fisher (Michael Elphick) is addressed by a doctor who suggests hypnotism as a way to unlock memories of a return trip to Europe, from which the policeman has been exiled. Everything which follows thus has the quality of unreliable subjectivity, memories dredged up in a trance. Von Trier obliterates any sense of realism (objective or cinematic) by constructing every image in meticulous physical detail yet without reference to a world outside the fiction. Everything takes place at night, drenched in perpetual rain and lit with a dense, oppressive sepia light provided by sodium lamps. This artificial visual texture imbues the film with an air of sickness which reflects the unhealthy psychology of the serial killer preying on children at the centre of the story.

Fisher has been called back by his old mentor Osborne (Esmond Knight) to help with a puzzling case. A few years earlier, a serial killer was murdering young girls who sell lottery tickets; the suspect, Harry Grey, had died in a fiery car crash, but now there’s another very similar murder. Osborne is the author of a text called Element of Crime in which he proposes that a detective, in order to solve the crime, has to immerse himself in the mind of the criminal he is pursuing, and he urges Fisher to follow in Grey’s footsteps, using a surveillance report which traced his movements up until the time of his death.

As Fisher goes back over the crimes, his personality begins to blend with that of his quarry … people he encounters conflate him with Grey; he becomes involved with a prostitute named Kim (Me Me Lai) who eventually turns out to have had a close relationship with Grey. In time, Fisher comprehends the pattern behind the murders, leading to the discovery of yet another victim. Identities blur to the point at which Fisher finds himself compelled to act out Grey’s obsession when he uses another young girl as bait; and finally he discovers that Osborne himself, following his own method, had taken on the persona of the killer.

By this time, the narrative (and Fisher) become overwhelmed by what has been present as a constant background of dystopian menace. This Europe is in chaos, a police state overrun by fascist gangs acting out rituals of violence rooted in a past which has never been fully dealt with. This cyclical reiteration of social trauma becomes a thread running through the trilogy, a madness which throws up individual aberrations like the crimes Fisher has come to investigate and into which he is absorbed.

More important than the details of the narrative itself is the dense visualization of the world in which they occur. The decay, the filth, the omnipresence of rain and water in general, through which the characters constantly have to wade and into which they eventually disappear (as will the protagonist of Europa), prefigure the miasma from which supernatural manifestations emerge in von Trier’s The Kingdom. This water and the detritus which clogs it also raise echoes of Tarkovsky’s imagery with its slow, deliberate tracking shots over streams full of weeds and discarded objects. There’s even a horse drawing a wagon loaded with apples which spill out to float away, recalling a dreamlike image from Ivan’s Childhood … which is not to say that von Trier shares Tarkovsky’s spiritual concerns, but rather that he taps into the imagery to reinforce the mood he is creating. As von Trier has said, for him film is a matter of emotions and moods rather than ideas, and Element of Crime stirs up deep strains of anxiety, a feeling of being trapped without possibility of escape.

Epidemic (1987)

Having declared his arrival in such a powerful way, von Trier took a very different tack with his second feature, Epidemic (1987) – made on a bet with Claes Kastholm Hansen, a consultant with the Danish Film Institute, that he could make a feature for only a million kroner (about US $150,000). The visual aesthetics of Element of Crime are completely discarded in favour of a starkly unadorned approach which seems to point towards the Dogme 95 manifesto. Largely improvised with a small cast, the film is something like an unreliable document of its own making.

A few days before von Trier and co-writer Niels Vørsel are due to deliver their new script to Hansen, a computer glitch erases the file before it can be printed. After a year’s work, it’s all gone and neither von Trier nor Vørsel can remember the story they’d written. So they have to come up with something quickly and settle on a story about Europe being ravaged by a plague, based on their research about the Black Death of the 14th Century. As they sketch in the broad outlines, we glimpse some of the scenes – with von Trier in the role of idealistic Doctor Mesmer, who defies the medical establishment to leave the safety of a walled city and go out into the contaminated world in an attempt to help a dying population. But eventually it becomes apparent that he himself is actually spreading the disease.

The loose, documentary-like sections with von Trier and Vorsel scrambling to create a new script are shot in grainy 16mm black-and-white, while the sequences from the proposed film are in more elegantly polished 35mm shot by Henning Bendtsen, who during a four-decade career had shot Carl Theodor Dreyer’s final two features, Ordet (1955) and Gertrud (1964). The “reality” parts contain a strain of humour absent from the “movie” parts and feel very much like the work of students who don’t take things very seriously. Vørsel tells a long story about wanting to know about New Jersey and pretending to be an adolescent in order to become pen-pal to some American teenage girls, which became problematic when one of them visited Denmark with her family – there’s a casual cruelty in his mocking of these girls who had no idea he was an adult man.

At another point, the pair drive to Germany where they visit Udo Kier, who tells an emotional story about his mother. Shortly before she died, she had told him for the first time about his own birth during an Allied firebombing raid in Cologne towards the end of the war. He had no idea that he had emerged in the midst of such horror and breaks down as he recounts the story for von Trier’s camera.

Late in the film, Hansen arrives to receive the script, obviously not impressed by the few pages of sketched notes he’s shown instead of a 150-page screenplay. Towards the end of dinner, another pair of guests arrive. Here the two threads come together in an unsettling way. The new arrivals are an experienced hypnotist and a medium, the latter being put into a trance in which she is urged to manifest the horror of the plague. According to the accounts of the participants, this was a genuine session of hypnosis and no one knew where it would lead. Soon the medium becomes distraught and the hypnotist loses control; the woman’s hysteria escalates and (here fantasy and reality definitely blur) she begins to manifest the physical signs of plague, huge pustules erupting on her neck and bursting as the disease spreads to others in the room. As in the proposed screenplay, with the young doctor spreading the disease, the writing of the script has unleashed the plague on the “real” world … the act of creation has brought destruction.

Epidemic seems to mock a great many things, beginning with the very idea of carefully crafted movies (like its obsessively crafted predecessor). But it also mocks the expectations of producers who provide backing, and the expectations of audiences who buy tickets to be entertained, and not least it mocks critics and the standards they like to apply to other people’s efforts. After this act of disdain for the Danish film industry, von Trier swung the pendulum as far as possible in the other direction with his next film, raising the level of craft and the complexity of narrative to new heights.

Europa (1991)

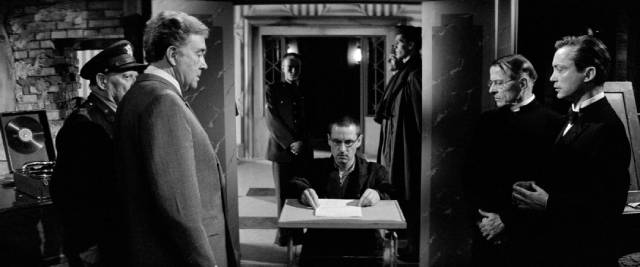

With Europa (1991), for which he had to seek funding outside of Denmark, von Trier says he deliberately set out to make a more commercial movie – and so he and Vørsel created a thriller which contains a love story, something easier for an audience to comprehend. But once again, his technique works against the narrative cliches. Where the distinctive look of Element of Crime was achieved with a combination of dense production design and the use of sodium lamps, for the new film von Trier went back to a technique devised in the early sound era. Process photography involves placing actors in front of a screen on which previously filmed backgrounds are projected. For studios, this was a valuable tool for adding scale to movies while controlling budgets; actors on a soundstage could be placed in any context – exotic landscapes, mountain tops, jungles, aboard a liner at sea, or simply sitting in a car. It wasn’t necessary to send cast and crew out on location; a second unit crew could bring the location back to the studio.

The original intent of process photography was to create an illusion of reality, but by the ’50s and ’60s, as more movies were shot on actual locations, the illusion had become unconvincing. Von Trier embraces its weaknesses as a tool for faking reality to create an obviously artificial version of the world, a kind of early, on-set photochemical precursor to the digital manipulations of something like Robert Rodriguez’s Sin City (2005). There’s a disconcerting quality to the look of Europa (once again shot by Henning Bendtsen) which creates simultaneously a sense of immediacy and an aesthetic distance, transforming its visual and narrative references to post-war Germany and the lingering legacy of Nazism into a mixture of memories and premonitions, a warning like Element of Crime about the rot which continues to permeate Europe.

The visual qualities of the film play even more strongly into the idea that what we see is being experienced in a state of hypnosis, something forcefully established from the start as the rich, soothing voice of Max von Sydow draws the audience into a trance. In Element of Crime, the doctor addresses himself to Fisher, placing the detective in a trance; in Europa, the disembodied hypnotic voice addresses us directly, assigning to the audience the identity of the protagonist, Leopold Kessler (Jean-Marc Barr), the son of a German emigrant who for some unclear reason has returned to Düsseldorf in August 1945 to apprentice under his uncle (Ernst-Hugo Järegård) as a sleeping car conductor for the Zentropa railway company.

Uncle Kessler is rigid and proud, clinging to rules which often seem arbitrary (and thus representing the compliance of ordinary Germans with an ideology they may well have absorbed without conscious examination); he looks on Leo with disdain, unable to believe him worthy of the role he is trying to fill (largely because he’s the son of a brother who betrayed his nation by leaving when the Nazis took power). Leo constantly falls short of expectations and the problem becomes progressively worse as he’s drawn into the romance and the thriller plot, both compelling distractions from his job.

The romance comes in the form of Katharina Hartmann (Barbara Sukowa), daughter of the railway company’s director, who seeks comfort from Leo when the train enters a long tunnel. He soon receives an invitation to dinner at the Hartmann house – much to the shock and dislike of Uncle Kessler – and finds himself in the unsteady realm of a ruling class destabilized by the end of Fascism. There’s Max Hartmann (Jørgen Reenberg), a man troubled by conscience, though it’s not clear whether this is due to his actions during the war or to what he now has to do to cling to power; Lawrence Hartmann (Udo Kier), a typically decadent son of privilege; Father (Erik Mork), a priest who clings to the family; and Colonel Harris (Eddie Constantine), a part of the Allied occupation authorities who is perfectly willing to prop up ex-Nazis like Max in order to consolidate control of the defeated nation.

As the forces of business and politics work to restore Germany, an insurgent group calling themselves Werewolves commit acts of sabotage, with Leo unwittingly being drawn into their plans because of his feelings for Katharina. Set in a country devastated by war, where it always seems to be night, the narrative plays out like classic noir – the somewhat naive and unsuspecting hero, the deceptively romantic femme fatale, the barely comprehended machinations of conflicting forces which push the protagonist inexorably towards his doom – but the style is simultaneously immersive and alienating, forcing the audience into watching from an ironic distance the young idealist brought to ruin by his own good intentions.

Von Trier’s visual technique is both exhilarating and claustrophobic. The extensive use of process photography required such precision in framing, blocking the actors and timing action and dialogue that Europa feels almost pathologically controlled. There are moments when the actors move in and out of foreground and background as they interact with one another across the plane which divides the elements of the image (further separated by having the foreground in colour and the background in black-and-white). At other times the technique deliberately fractures elements of the image, violating any sense of natural scale, as in the scene in which a young boy assassinates a newly appointed Jewish mayor, with the horrified victim looming large in the background over the diminutive killer in the foreground.

There’s no breathing room, which some critics saw as an artistic failure (as David Thompson put it in his Biographical Dictionary of Film, von Trier is “brilliant in a way that gives the term a bad name. He knows no reality – only film”), but this obsessive quality supports the theme of a continent trapped in the thrall of an ideology which dooms it to endlessly repeat a cycle of violence and oppression. As the hypnotic voice of the narrator concludes, “You want to wake up, to free yourself of the image of Europa, but it is not possible.”

In a sense, von Trier agreed to some degree with this evaluation, realizing that this kind of tightly controlled construction of his imagery had reached its apotheosis. When he made his next feature, five years later, it was with a raw, improvisational style, the radical hand-held, jaggedly edited Breaking the Waves (1996), which paved the way for the austerity of Dogme and The Idiots (1998). The pendulum having swung so far in the opposite direction, his subsequent work has been an attempt to find some balance between these extremes, a letting go blending with formal experimentation. But it all started with the films of the Europe Trilogy, which stand as a remarkable achievement which was begun when the filmmaker was only in his mid-20s.

*

The disks

Criterion’s three-disk set features new scans of all three films – Element of Crime and Epidemic in 3K from the original 16mm negatives, Europa in 4K from the 35mm negative – and given the differing quality of the sources, they all have excellent image and sound.

The supplements

The set provides an exhaustive account of the trilogy’s production and von Trier’s working methods and intentions with seven-hours of documentaries, interviews and student films, as well as commentaries from Von Trier and his collaborators. All of this material is archival, some of it from the time of the films’ original release (1984 to 1991), much of it from 2005 when retrospective interviews were conducted for a four-disk DVD edition released in Germany and the UK.

While it would have been interesting to hear from von Trier with an additional eighteen years of perspective, this older material is a fascinating deep dive into his creative process, occasionally repetitive, but well worth exploring. Criterion’s year is definitely off to a great start.

The set includes a booklet with an enthusiastic essay by Howard Hampton.

Comments