Thomas Vinterberg’s Festen (The Celebration,1998):

Criterion Blu-ray review

in Thomas Vinterberg’s Festen (The Celebration, 1998)

Dogme 95 was a provocation, a finger deliberately jabbed in the eye of mainstream cinema. Drafted in a burst of rebellious energy by Lars Von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg, its tenets proposed the rejection of a century of deeply ingrained practices and habits. The two filmmakers felt that the apparatus of filmmaking, the technical foundation of the movies, had come to dictate creative choices. After a hundred years, cinema had become moribund and it was time to shake things up.

What they came up with in their manifesto was a conscious rejection of every technical crutch filmmakers had come to take for granted – the use of constructed sets, of artificial lights, of self-conscious camerawork, of music … everything which filmmakers and audiences had come to take for granted and which made filmmaking practice and audience response predictable.

For Von Trier, who at the time already had a couple of decades of filmmaking experience behind him, this was an attempt at self-renewal, a way of breaking his own creative habits, even though his work to date had already pushed hard against mainstream norms. But for the younger Vinterberg, who had just a few shorts and one feature behind him, it was more an act of youthful rebellion. The ten stringent rules which embodied the manifesto’s “vow of chastity” were widely mocked when Von Trier announced them at a conference in Paris on March 14, 1995. No one expected much to come from what seemed a rather naive gesture, but Von Trier and Vinterberg – and eventually others who signed on – were determined to carry out this plan to reform cinema.

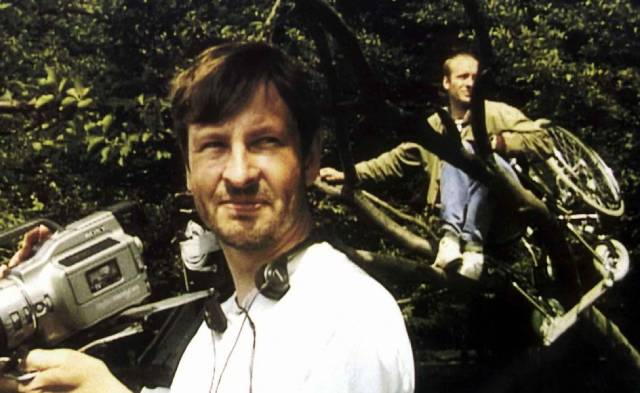

Whether by design or mere coincidence, Dogme 95 was conceived during the period when video and film technologies were overlapping on the way to what we now take for granted. The availability of small, lightweight video cameras facilitated the core Dogme principle of discarding the weighty apparatus of production. The nature of video at the time – lower resolution, coarser sensitivity to colour and contrast – also undermined traditional standards of visual aesthetics. The image had a raw quality which freed attention from a more detached, contemplative position to an immediate engagement with what was contained within the image – a direct connection with the actors and the drama they were involved in. From this arose the first major paradox of Dogme: a combination of documentary immediacy, an engagement with seemingly unmediated reality, and a powerful sense of theatricality. Dogme was all about performance (something embedded in the fabric of the fourth Dogme feature, Kristian Levring’s The King is Alive [2000]).

This made Thomas Vinterberg’s second feature, Festen (The Celebration, 1998), an ideal first experiment. The superficial crudity of the film’s technical apparatus seems to give direct access to the intense emotional drama at play. When I first saw The Celebration at the Toronto International Film Festival is 1998, I felt devastated for days. There were no defences against its emotional impact. Seeing it again now on Criterion’s Blu-ray, my fourth or fifth viewing, that impact remains just as powerful, though as with anything which has become more familiar, it’s possible to see it with a kind of dual perspective; the immediacy is still there, but one can better see how it has been achieved.

This brings to light the second paradox of Dogme: no matter what strictures the filmmaker might impose on him- or herself, the mere act of filmmaking draws the creator in certain directions. A Dogme film may not have the qualities of a professionally produced studio movie, but it is nonetheless a crafted artifact. It may lack a director’s name in the credits (rule #10), but it is clearly shaped by a particular creative sensibility. What gives the film its remarkable potency is the quality of Vinterberg’s script (co-written with Mogens Rukov) and more particularly his work with the cast, all observed with the nervous energy of Anthony Dod Mantle’s camerawork … while the surface trappings of mainstream cinema have been stripped away, the potent core of the hundred-year-old art form remains; the audience experiences other lives vicariously and feels the heightened emotions to which the movies give seemingly unfiltered access.

At its heart, The Celebration is a family melodrama. Perhaps more than its technical experiment, it is most radical in that it shifts melodrama’s traditional focus from female emotional and psychological states to a raw depiction of male trauma, exploring a vulnerability usually hidden. This too amplifies the film’s impact because it penetrates the complacency we may too often feel when witnessing the female trauma which has been embedded in popular cinema since its beginnings.

Despite the ostensible realism of the film’s technique, there is a highly constructed quality to the narrative. The action is concentrated in a brief period – from one afternoon to the following morning – and in holding it all together Vinterberg has to gloss over certain implausibilities in order to keep all the characters in place. At the start, a large group of people gather at an imposing country hotel to celebrate the owner’s sixtieth birthday; when dark, uncomfortable family secrets are exposed, and social discomfort rapidly increases, ways have to be found to prevent everyone escaping. The overt device of having the hotel’s staff steal everyone’s car keys is an implausible contrivance; and yet something else comes into play which enriches one of the film’s themes – the ability of these bourgeois people to selectively ignore what makes them uncomfortable and to continue to perform their social roles no matter what threatens to overturn their settled perception of the world and their place within it.

When son Christian (Ulrich Thomsen) gives his speech at the birthday dinner and reveals that his father Helge (Henning Moritzen) had sexually abused him and his twin sister, who recently committed suicide, the gathered guests are initially made uncomfortable, but quickly bounce back by simply rejecting the revelation – Christian, an intense and unhappy character, is obviously just airing some personal emotional issues by making outrageous and unbelievable accusations.

Having done what he came to do, Christian prepares to leave, but he’s confronted by his childhood friend Kim (Bjarne Henriksen), the hotel’s head cook, who challenges him to stay and see it through, otherwise he’s accomplished nothing. Here, the familial conflict takes on a larger class element – the staff support Christian in his desire to force accountability on the patriarch whose social position and economic power holds sway over all their lives.

And so Christian, despite the emotional toll, returns to the battle with a toast in which he calls Helge the murderer of his sister. The cracks become harder to paper over and the guests look for ways out – with their cars immobilized, they retreat to other rooms to drink and dance – while Christian’s siblings, Helene (Paprika Steen) and Michael (Thomas Bo Larsen), are drawn into his rebellion in different ways. Helene, rebelling herself by bringing her Black boyfriend Gbatokai (Gbatokai Dakinah) to the party, knows that Christian is telling the truth (she has found a letter from the dead sister), but feels this is neither the time nor place to bring up the past; Michael on the other hand, in the midst of his own turbulent marriage, is driven to fury and attacks Christian for destroying his sense of the family (within which he, ironically, feels he isn’t fully accepted).

As the night goes on and emotional connections among the characters shift and evolve, the technical limitations of the Dogme rules reinforce the dramatic trajectory – the growing darkness causes the image to break down, becoming murky with excessive digital grain. All the social rules which have kept this society together by concealing its unpleasant secrets and maintaining its well-defined class divisions are dissolving just as the image itself is disintegrating. While this suggests a possibility of new alignments, the film’s conclusion offers no pat resolution.

At breakfast, the exhausted, emotionally battered partygoers gather for breakfast and Helge appears and finally takes some kind of responsibility for what he did to his children. He has lost his honoured position in this society – but Christian hasn’t been healed by his act of emotional courage. Having made the abuse public doesn’t erase the trauma of what was done to him or the loss of his twin sister, although there is a possibility of progress in his invitation to waitress Pia (Trine Dyrholm) to leave with him. In this, The Celebration eschews the cathartic tradition of melodrama for a more realistic recognition of the messiness of human psychology.

*

Does The Celebration meet all the requirements specified in the Dogme 95 manifesto? For the most part, yes, because the ten “rules” relate essentially to particular technical qualities. It was 1) shot on location, for the most part using only what was available on-site without additional art department additions; 2) only immediate direct sound was used, although this was slightly fudged by having crew members provide some Foley just outside of the frame; 3) it was shot entirely hand-held; 4) it’s in colour, mostly without the use of additional lights; 5) optical effects and filters weren’t used; 6) “superficial action”, as defined by the manifesto, was avoided – that is, there are no guns or murders, although there is a hidden letter which comes to light and swings the dramatic trajectory at a crucial moment, so… ; 7) for the most part, temporal and geographic unity are maintained, although towards the end, as Christian undergoes an emotional collapse, it does become subjective, with him having a vision of his dead sister, which does seem to break the rules; 8) it can’t really be classed as a “genre movie”, except in the general sense that it can be considered a family melodrama; 9) it’s certainly shot in the Academy ratio (1.33:1), though as a rule this seems a bit more arbitrary than most; and 10) Vinterberg doesn’t take a director credit (however, he is listed as co-writer).

Where things become a bit more complicated is with the manifesto’s concluding note:

“Furthermore I swear as a director to refrain from personal taste! I am no longer an artist. I swear to refrain from creating a ‘work’, as I regard the instant as more important than the whole. My supreme goal is to force the truth out of my characters and settings. I swear to do so by all the means available and at the cost of any good taste and any aesthetic considerations.”

While any revolutionary manifesto must by its nature be extreme (it declares its intention to break with a long-standing status quo), this last has a built-in paradox. While it acknowledges that filmmaking is a creative enterprise, it demands that the filmmaker refrain from any creative action which influences what is being created. An impossibility.

While The Celebration adheres (mostly) to the ten rules, it is very much shaped by Vinterberg’s creative impulses, beginning with the tightly structured script co-written with Mogens Rukov. While room is provided for accident and improvisation, there is a well-defined narrative conveying rich psychological detail. Having initiated the process, aesthetic considerations inevitably creep in. If the technical quality of the video imagery is unacceptable by industry standards, beauty nonetheless shines through that rough surface – in the dynamic energy of Mantle’s hand-held camerawork, in the expressiveness of the performers: Christian’s suppressed pain, the combative marital relationship of Michael and Mette (Helle Dolleris), the confusion of Helge as his life-long certainty about his own authority is stripped away, the crumbling poise of the mother Else (Birthe Neumann), the blunt honesty of Kim, and the radiant openness of the waitress Pia whose unguarded affection for Christian displays a deep empathy which serves as a counterforce to the bourgeois inertia against which Christian rebels.

The simple act of telling a story negates the manifesto’s demand that the filmmaker somehow erase himself from the process of filmmaking, and aesthetics and choices dictated by the filmmaker’s own personality and experience flood back in.

*

The disk

By the technical standards we’ve all become used to, the image on Criterion’s Blu-ray might appear problematic to an unprepared viewer, but the quality is inherent in the film’s origins on Digi-Beta, a pre-hi-def format. The original tapes were converted to 35mm for theatrical release in 1998, and the transfer here was made from an answer print struck from the intermediate negative – which means that what we now see has passed through several digital and film generations. The graininess and lack of fine detail are inherent to the source and are therefore integral to the film, a physical expression of the Dogme 95 philosophy. As such it would be impossible to imagine the film’s impact without this visual analogue of the turbulent emotional content of the narrative.

The audio was also restricted by the Dogme rules, with nothing to be added to what was captured during the shoot – no sound effects, no music, no dubbing. Nonetheless, dialogue is clear. In some of the disk extras it’s amusing to see that Vinterberg fudged the rules slightly by creating some on-set Foley to add impact to scenes like the ones in which Christian and Helge each receive a beating, the sound of the blows actually being created by crew members just off-camera.

The supplements

Criterion have supported Vinterberg’s film with so much supplementary material that it required a second disk. The feature disk itself gets a commentary from Vinterberg recorded in 2005, plus a new interview with the director (18:49), in both of which he talks about the origins of the Dogme rules and how they affected his creative process. There’s also a trailer (1:40).

The second disk contains more than four-and-a-half hours of additional material. At the time of writing, I still haven’t watched it all, but there doesn’t seem to be anything extraneous. Two short films by Vinterberg, including his film school thesis project, display not only his interest in exploring the effects of (male) emotional trauma, but also his skill with actors. In the thesis project, Last Round (32:51, 1993), he focuses on Lars (Thomas Bo Larsen), a man in a hyper-agitated state who has stolen money from his boss and is using it to have a final fling with his friends, a farewell gesture because he only has a few months left to live. In The Boy Who Walked Backwards (38:43, 1995), nine-year-old Andreas (Holger Thaarup) seeks a way to deal with his grief after the death of his older brother. Both films display great assurance with classical narrative form; they have an emotional rawness and intensity similar to The Celebration, ironically suggesting that the technical and stylistic extremes of the feature were not absolutely necessary to achieve the effect Vinterberg was looking for.

There are twelve deleted/extended scenes (45:05), with optional commentary. While some of these were obviously dropped because they were somewhat redundant, repeating things already clearly expressed, others take the narrative off on tangents which diverge from the core theme, at times with a jarringly different tone. These paths-not-taken are interesting because they reveal the exploratory nature of Vinterberg’s process, making the clarity of the finished film that much more impressive.

There’s a behind-the-scenes featurette from the film’s premiere in 1998 (24:06), plus two more from 2005 with interviews with Vinterberg and members of the cast and crew (9:36, 26:26), and Shari Roman’s ADM:DOP (12:13, 2003), a short, impressionistic portrait of cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle in which he talks of his approach to his work, with particular attention to his collaborations with Vinterberg and Von Trier.

Finally, The Purified (1:07:50) is a documentary from 2002 in which filmmaker Jesper Jargil follows Von Trier, Vinterberg and later Dogme signatories Kristian Levring and Søren Kragh-Jacobsen from the original declaration of the manifesto in Paris through the production of the first four Dogme features. This is fascinating on a number of levels, not least for the glimpses it provides of the shooting of The Celebration, Von Trier’s The Idiots (1998), Kragh-Jacobsen’s Mifune (1999) and Levring’s The King is Alive (2000). The real substance, though, are the sessions in which the four filmmakers watch and critique each other’s work, with a thread of commentary from writer Mogens Rukov woven through it all to provide the philosophical/conceptual basis of Dogme 95 on which everything rests. While one of the rationales for the manifesto was the intention to strip ego out of the filmmaking process, the group sessions are full of clashing egos, with the always-prickly Von Trier ever ready to take the others to task for violating the rules. All of them acknowledge that his own film, The Idiots, is perhaps the one which comes closest to fulfilling the manifesto’s intentions in its improvised formlessness (it might be noted that it’s also one of Von Trier’s least satisfying features), while he berates them for their inability to let go of a tendency to seek dramatic form and, more significantly, aesthetic qualities which pull their work back towards established ideas if cinema. What becomes clear is that the creative act itself has certain imperatives and these have long been embedded in the processes of cinematic creation. From the point of view of Dogme’s stated aims, it is apparent that the “vow of chastity” is an unattainable ideal – but an ideal within which each filmmaker finds a way to achieve his own sense of creative freedom. In effect, it gives them each an opportunity to work without a net, to take chances and not fear the possibility of failure. In the gesture of rejecting “cinema” they are all reinvigorated to rediscover what cinema actually means to them, to throw off the weight of accumulated technical and commercial imperatives and return to the sense of discovery with which the pioneers launched the 20th Century’s art form a hundred years earlier.

That sense of discovery makes The Celebration one of the most exhilarating films of its time and Criterion’s two-disk edition captures all the reasons it has such impact and illuminates its creative and commercial importance.

The booklet reprints the entire Dogme 95 manifesto along with an essay by writer and filmmaker Michael Koresky.

Comments