D.A. Pennebaker’s Original Cast Album: “Company” (1970):

Criterion Blu-ray review

in D.A. Pennebaker’s Original Cast Album: “Company” (1970)

To make a gross generalization, there was a radical change in documentary film in the late-’50s, early ’60s. Although there were exceptions, until then documentary was viewed as informational, educational, and films were scripted and narrated, with visuals used to illustrate the points being made. The shift was propelled by the development of lighter-weight camera and sound equipment and faster film stocks, expanding the range of conditions within which the filmmaker could capture footage. (A decade or so earlier, lightweight news cameras enabled filmmakers to record events on World War Two battlefields, introducing audiences to a kind of immediacy not previously experienced, though generally there was little or no accompanying live sound.)

A new style, dubbed variously as Cinéma vérité or direct cinema, quickly emerged in many countries – practiced by people like Michel Brault in Canada, Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin in France, and Robert Drew and Richard Leacock in the States – with filmmakers exploring the world as it happened rather than constructing a preconceived idea of the world. In the U.S., the undisputed masters of this new movement were the Maysles brothers, Albert and David, and D.A. Pennebaker. Their approaches were somewhat different – the Maysles brothers often took a novelistic approach to character, while Pennebaker was frequently more interested in observing process, how people accomplish the things they do. (A few years later Frederick Wiseman took up this focus on process and has pursued it obsessively for more than fifty years in his studies of institutions and how they work.)

Throughout his career Pennebaker had a deep interest in performance. While this showed most often in the many music documentaries he made, it also extended to films like Town Bloody Hall (1979) and even The War Room (1993), in which a political campaign can be seen as a complex show constructed for the media to sell the idea of a candidate to the electorate. His breakthrough film was Dont Look Back (1967), a brutally revealing record of Bob Dylan’s 1965 British tour. The immediacy of Pennebaker’s ever-present camera reveals both Dylan’s remarkable talent and his unpleasant shortcomings as a human being. It remains surprising that the singer approved of the results.

The nature of that tour provided sufficient time for Pennebaker to capture a complex, nuanced portrait of the artist. Three years later, the filmmaker was presented with a very different challenge. Producer Daniel Melnick suggested that he make a pilot episode for a proposed series to be called Original Cast Album, which would document just that – the recording sessions for albums of successful Broadway musicals. These sessions, apparently, usually occurred over a single day (and night) following the opening weekend. Part promotional material, part permanent record of the show, these recordings required a gruelling marathon effort from the cast who, usually on a Sunday morning, would begin just hours after having given a Saturday night performance before a live audience.

Pennebaker accepted the challenge and he was given permission to shoot the session for Stephen Sondheim’s Company, the composer-lyricist’s first show in a career-long effort to transform musical theatre. (Prior to Company, he had provided lyrics for a number of major shows, but had not yet had an opportunity to compose scores, which is what he really wanted to do.)

Naturally the dynamics and energy of a recording studio are very different from those of a crowded theatre; and standing in front of a microphone is physically far from moving, and dancing, on a stage. Without the natural flow of a live show and with the necessity to deliver a definitive performance under strict time constraints, the singers were under enormous pressure. And yet Pennebaker and his collaborators, including Richard Leacock and Jim Desmond with additional cameras, were given free access to the studio and recording booth, getting close to singers, orchestra and technical crew for an intimate view of the work which goes into the creation of art.

Given multiple takes of the songs, Pennebaker had plenty of coverage to construct dynamic sequences in which he could intercut the singers, the musicians, record producer Thomas Shepard and Sondheim himself. The film offers an interesting counterpoint between the energy (and apparent pleasure) of the singers and the tension of those capturing the performance on tape. As the day progresses into evening and then night, the stress increases; Sondheim focuses on minute details, coaching performers on something as small as a single syllable, the shift in a note from what he had originally intended to something the performer was more comfortable with. Shepard is concerned with the balance between parts of the orchestra and the energy being delivered by the singers. One singer, delivering a long very fast passage, is concerned about where she can draw a breath in the midst of the flow…

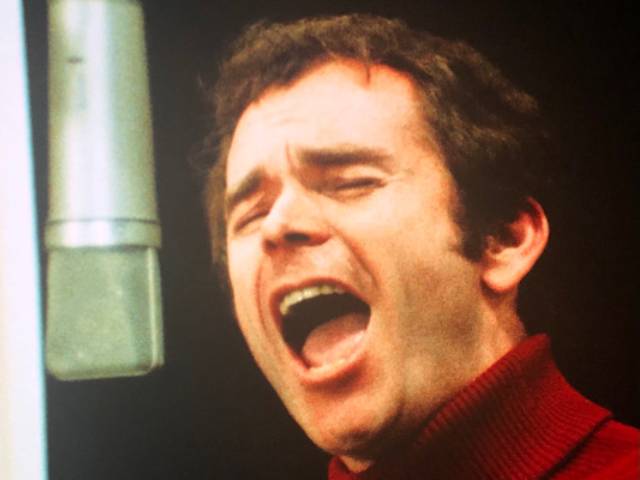

Pennebaker’s skill lies in a seemingly effortless ability to find the perfect angle for every moment, his camera swinging from one focus point to the next at exactly the right time. Although the day and night are ultimately compressed into fifty-three minutes, the film has a seamless flow; the progression of energy and enthusiasm towards exhaustion and a growing anxiety that it might not be possible to capture a definitive performance becomes focused on Elaine Stritch and the final, late-night attempt to record her show-stopping number “The Ladies Who Lunch”. Originally intended to be recorded earlier, it was bumped to accommodate the show’s lead Dean Jones who was anxious about his own big number, “Being Alive”.

Earlier, Stritch had a seemingly relaxed attitude, enjoying herself, exuding ease and confidence, smiling with pleasure – but by the time she’s asked to deliver her number, she’s obviously tired (and apparently had had more than a few drinks) and she, along with Sondheim and Shepard, knows that her voice isn’t up to the demands of the song. It’s fascinating, and increasingly painful, to watch the strategies she uses in trying to get through it … she speaks the lines, rather than singing them, she drops the register to decrease the strain on her voice. And in the booth Sondheim looks as if he’s facing the possibility of failure. Shepard loses patience and becomes harsh in his criticism of Stritch’s performance – but no harsher than Stritch herself who angrily listens to the playback until she finally yells at her recorded self to “shut up!”

This all would have provided the documentary with a depressing end, but Shepard makes the decision to record the orchestra’s rendition of the number and bring Stritch back two days later at 10:00AM to lay down the vocals. Fresh, re-energized, she delivers what was to be considered the definitive rendition of the song and the film ends on a high note, validating the effort to capture a permanent record of something – the theatrical experience – which by its very nature was conceived to be experienced as transient, an exchange between performers and live audience.

Although I know little about music, and am certainly no singer, it seems obvious that Sondheim’s musical numbers are extremely complex and demanding and one of the fascinating aspects of the documentary is the way in which it lays bare the sheer physical and mental effort required to produce what ultimately sounds like an effortless performance. This is a record of the enormous amount of concealed labour hidden beneath an exhilarating (and at times rather dark) entertainment.

If I were to have one complaint about Original Cast Album: “Company” it would be that, because it was conceived as the pilot for a TV series, it’s too compressed at just fifty-three minutes. It’s a pity that, when the series failed to materialize, Pennebaker didn’t go back to the material and expand the film because there must have been so much more to the process even than what we now see. It would also have been nice to hear more of the songs and see Sondheim and the performers moulding them for this official record… But that’s just an indication of my greed as a viewer to have more of something which, as it is, is so good.

Criterion have to some degree provided that extra with the supplements they’ve added to the disk. In fact, some of my comments above have been gleaned from those supplements rather than from the film itself. A great deal of context is provided about the historical importance of this particular musical and about Sondheim’s place in American musical theatre, and also about his creative process and the ways in which his work has been shaped by his collaborators, particularly orchestrator Jonathan Tunick. Overall, the disk is not so much about the theatrical artifact – Company itself and the album being made from it – as it is about the creative labour which produced that artifact; it’s about artistic creation as work. (It’s also, rather strikingly, about the ubiquitous presence of cigarettes in that earlier time, not just in the booth, where Sondheim is seldom without one, but also in the studio where a performer in the midst of a number has a smoking cigarette casually held by the fingers of a hand with which he gestures as he sings.)

*

The disk

Criterion’s Blu-ray has been mastered from a 4K transfer from the original 16mm reversal stock (it wasn’t even filmed on negative). Needless to say, the image is very grainy, but the colours are fine and there’s a lot of detail in the image. The technical quality adds to the air of immediacy, of shots being grabbed on the fly, in the moment … which is one of the strengths (and pleasures) of Cinéma vérité: this is happening now and won’t be repeated. The sound, for the most part, is excellent, having been taken from the original 1/4-inch recordings and 16mm magnetic tracks; the music and vocals have genuine depth.

The supplements

There are two commentary tracks, which I haven’t had time to listen to yet; one from 2001 with Pennebaker, Stritch and Hal Prince, who directed the show on Broadway, the second a new track with Sondheim. One of the featurettes is additional material from the 2001 commentary recording session (11:46).

Two new featurettes provide a wealth of information about the documentary, the original show, and the creative process itself. The first is a conversation between Sondheim and Tunick, moderated by theatre critic Frank Rich (29:27), which is lively and enthusiastic and illuminating about how the show was created – for instance, Sondheim does all his composing on a piano and Tunick translates that work into the complex interactions of a full orchestra, essentially taking the composer’s architectural drawings and transforming them into the three-dimensional aural construction of the show, not merely a technical task, but a vital collaborative effort. We also learn that years later producer Shepard offered a public apology after a screening of the film for the harsh criticisms he had levelled at the performers, acknowledging that his job was to be supportive … that he did behave as we see is another indication of the incredible stress everyone was under to deliver on such a tight schedule.

There is also an engaging conversation between Jonathan Tunick and author Ted Chapin (18:39) about the arranger’s career and his work on this particular show. Among many details, Tunick mentions that during the session he repeatedly mentioned that he couldn’t hear the guitar in the orchestra and was repeatedly told not to worry, that it would be “fixed in the mix”, only to discover at the end of the session that the guitar mic had been unplugged – so for him, the entire recording is marred by the absence of an important instrumental element which he considered gave the show an edge; this “official record” of Company is thus softer than it should have been.

I’m ambivalent about the other two extras. The first is a 2019 episode of the television series Documentary Now! (24:37), which parodies Pennebaker’s film by restaging many of its distinctive moments as an account of the album recording session for a failed musical called Co-op. It’s clever enough, with a good cast and decent pastiche songs, but I can’t help wondering just what in the original film is being mocked.

This is accompanied by a Zoom session in which co-writer and star John Mulaney is joined by multiple members of the cast and crew to discuss the original documentary and their parody (33:10). What is clear is that Pennebaker’s film has a prominent place in modern theatre history and that their parody was intended as an act of homage … perhaps it might have worked better for me if I hadn’t watched it immediately after the documentary.

The booklet essay, which provides even more context and detail about both the musical and the documentary, is by Mark Harris.

Comments

Did you watch the tape and looked at the photos in your article? The picture of Dean Jones is his duet of “Barcelona”, not “Being Alive”. You knew they brought Elaine Stritch back in two days so her voice was fresh to sing “Ladies Who Lunch”. Your photos show her wearing the same clothes both days? She explained her clothing in one of the extra recordings.

Correct… and corrected.