An evening with ’50s monsters

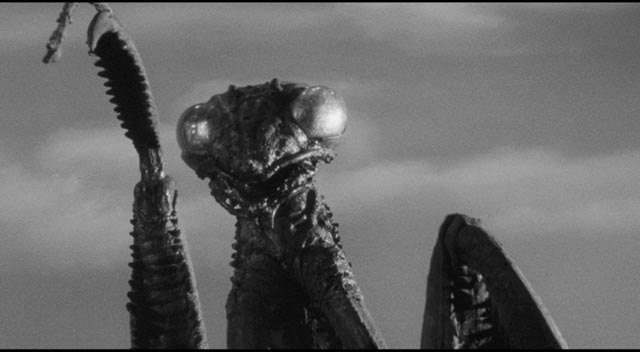

The Deadly Mantis (Nathan Juran, 1957)

I recently spent another evening at my friend Steve’s, following the well-worn routine of dinner, drinks and – after his wife Val went off to watch a hockey game in another room – some movie viewing. While the main event was yet another restored 3D movie from the brief 1953 flowering of the form, the second feature was a low-end creature feature produced by Universal’s in-house specialist William Alland. Best known for his support of Jack Arnold’s mid-’50s string of genre greats, beginning with It Came From Outer Space (1953), and Universal’s bid for big-budget sci-fi respectability with This Island Earth (Joseph M. Newman, 1955), as the decade wore on Alland squeezed his budgets ever tighter, with consequent diminishing returns in quality. Despite occasional bright lights like Arnold’s The Space Children and Eugène Lourié’s The Colossus of New York (both 1958, and both compromised by insufficient production resources), he churned out cheapies like The Mole People (1956) and The Land Unknown (1957), both directed by Virgil W. Vogel (who directed an enormous quantity of television right up to his death at age 76), which are notable for an excessive reliance on stock footage and sub-par effects.

The Deadly Mantis (1957) is one of the most enjoyable of these cheese-fests. Directed by Nathan Juran, barely a journeyman – best known for being hired by Charles Schneer to stay out of Ray Harryhausen’s way on 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957), The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) and First Men in the Moon (1964), and of course for Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958) – Mantis never rises to the demented level of Sam Katzman’s The Giant Claw (Fred F. Sears, 1957), released just a month earlier. But it shares a general structure with that movie, as well as with The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (Eugène Lourié, 1953) and Them! (Gordon Douglas, 1954). A catastrophic event (here natural rather than atomic) releases a giant creature from its ancient ice tomb and it rampages around the continent wreaking havoc while scientists and the military try to figure out first what it is and then what to do about it.

What it is is a colossal insect – no surprise there, given the title – which smashes buildings, brings down planes and (discretely off-camera) eats people. In flight, the creature doesn’t look much like a mantis, but on the ground it’s often quite impressive, particularly in the Them!-inspired climactic sequence in the Manhattan Tunnel where our heroes gas and shoot it to death. But for the most part, the movie goes through the familiar motions – no-nonsense military man (Craig Stevens), no-nonsense scientist (William Hopper), fearless, intrepid female assistant (Alix Talton) destined to be tamed by one of the men – and interminable stock footage montages. In the prologue, the camera moves in very slowly on a map of the world, seemingly unable to decide where we’re going before it finally settles on a remote spot near Antarctica where a volcanic island explodes … then moves equally slowly all the way back up to the North Pole where, in “an equal and opposite reaction”, a glacier cracks open releasing the bug.

This is so tedious that even commentary track contributor Tom Weaver repeatedly falls silent during this opening section, waiting for something to happen. The Deadly Mantis is definitely a movie to watch with friends primed with a few drinks. So it’s not surprising that Shout! Factory’s Blu-ray includes the Mystery Science Theatre 3000 episode devoted to it. Steve and I watched the opening of this after viewing the feature and were both irritated to find ourselves laughing – we both hate the smug condescension of MST3K – and assumed our reaction was largely due to the evening’s alcohol intake. I did watch the entire episode the next day, and discovered that almost everything the MST3K crew said repeated comments Steve and I had said to each other while watching the movie … which confirmed that the show’s writers were really not much funnier or more inventive than the average fan and it’s always more amusing to add your own commentary than to sit there and listen to someone else crack wise.

*

The Maze (William Cameron Menzies, 1953)

The evening’s main event was much more interesting. I first read about William Cameron Menzies’ The Maze (1953) in various film books almost fifty years ago – particularly John Baxter’s Science Fiction in the Cinema (Paperback Library, 1970), which dismisses the content while praising Menzies’ visual skills. Menzies was a designer first, filmmaker second – he essentially created the category of Production Designer with his Oscar-winning work on Gone With the Wind (1939) – and that fact drew him repeatedly towards the fantastic, from early-’30s mysteries like The Spider (1931) and Chandu the Magician (1932) to his biggest production, H.G. Wells’ Things to Come (1936), and three low-budget genre projects in the 1950s, beginning with the compromised The Whip Hand (1951), fan-favourite Invaders From Mars (1953) and finally his sole foray into 3D, The Maze (also 1953).

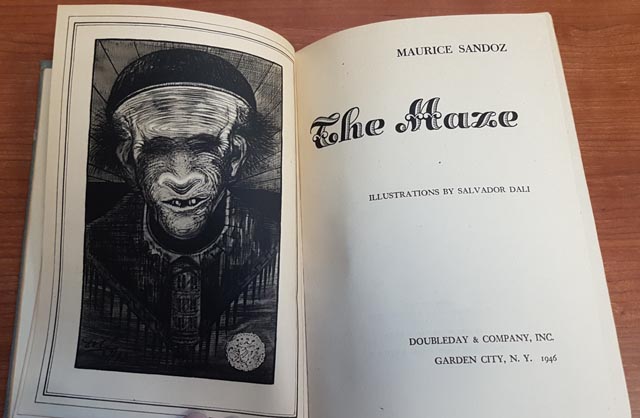

Menzies’ design sense already emphasized composition-in-depth, so it isn’t surprising to find that he was a natural in 3D. While he does his share of poking the audience in the eye, what distinguishes The Maze is the sense of space he instills in the imagery, particularly in the vast Gothic interiors of the film’s main setting, a Scottish castle. Adapted from a novella by Swiss writer Maurice Sandoz (about whom I can find very little information on-line), The Maze is an oddity which many critics (and viewers) find ridiculous. Perhaps it helps if you already know where it’s leading when you watch it and aren’t taken by surprise by its climactic revelation. Personally, I found it oddly charming.

Opening at a resort on the Riviera, the film introduces us to improbable Scottish aristocrat Gerald MacTeam (Richard Carlson, who thankfully makes no attempt at an accent), his fiancee Kitty Murray (Veronica Hurst) and her guardian, Aunt Edith (Katherine Emery). All are looking forward to an upcoming wedding, but Gerald receives word from the family estate and has to rush back to Scotland, promising to stay in touch. But nothing is heard for weeks until he finally writes to break off the engagement with no explanation.

Kitty insists that she is going to go and find out what’s happened and Aunt Edith agrees to go with her. Gerald has aged shockingly in the short time he’s been away and is angry to see them dumped on his doorstep. The castle is ancient, devoid of modern conveniences, and Gerald and the taciturn staff are inhospitable and unwelcoming. At night, Kitty and Aunt Edith find their doors locked and hear strange noises out in the hallway. In other words, we’re in the realm of Gothic Romance and dark family secrets. Gerald, his uncle having died, has been forced to assume his preordained position as master of the family estate, a burden which obviously weighs heavily on him. And which precludes any possibility of marriage.

Kitty and Aunt Edith explore the castle and its grounds – which include the title maze – trying to uncover the nature of whatever has brought about such a change in Gerald. They glimpse strange things, hear strange noises, and finally call on a group of friends to come and pay a “surprise visit” to try and force the issue. Gerald is furious when these old friends show up “spontaneously” on his doorstep, but has no choice but to play host. Eventually, their presence does crack the secrecy which hangs over the castle and in a climax which makes you wonder how the filmmakers expected to get away with it we finally learn the history of the MacTeam family and the dark secret which has hung over them for two centuries.

It’s difficult to believe that anyone at this stage doesn’t know that secret, but I guess I have to issue the standard SPOILER ALERT here. Faithful to the source story, the film offers a “scientific” explanation for the pall of Gothic horror which hangs over the MacTeam castle. Two hundred years earlier, the wife of the lord gave birth to a monstrous mutant, a child which had been arrested at an early stage of fetal development, emerging as an amphibian with a human brain … in short, a giant, sentient toad which has lived and ruled the estate for two centuries, devoted to transforming the land to a fertile agricultural showcase for the benefit of the peasants who live there. As startling and amusing as this creature appears on screen, it’s the source of all the melancholy gloom which hangs over the movie – something of a proto-Elephant Man, a good soul trapped in a monstrous body, tended with care by faithful retainers. Gerald, like his predecessors, is lord of the estate in name only; his role is to carry out the will of this ancient creature, to serve as yet one more guardian. It’s all endearingly absurd.

Menzies plays it straight, treating the absurdity seriously as he draws every ounce of atmosphere from the gloomy castle sets and bleak surrounding landscape. Is The Maze a good film? It depends on what standards you apply. It’s one of those cases where, if you’re willing to suspend disbelief and follow the concept to its logical conclusion, there’s much to enjoy; if you think the central concept – rooted in teratology, but taken to an absurd extreme – is simply too ridiculous to countenance, then you’ll dismiss it all as nonsense. But performances are good, design (by Menzies) and photography (by Harry Neumann) excellent. Needless to say, Steve and I thoroughly enjoyed it.

In fact, having listened to Tom Weaver’s commentary the next day – in which I learned that Sandoz’ story was “based on” an actual Scottish legend about the castle of Glamis and its dark family secrets – I found and ordered a copy of the book on-line. It turns out that the adaptation (by Daniel B. Ullman, who seems to have specialized in westerns and war films rather than fantasy) is quite faithful in tone and incident to the story – the biggest difference being expanding the part of Kitty. In the story, it’s Aunt Edith alone who goes to the castle to find out why Gerald has broken off the engagement, while the script makes Kitty a much more active participant.

The book, published in the U.S. by Doubleday & Co, in 1946, is notable for containing thirteen full-page illustrations by Dali.

*

There was one strange thing about the evening. Early in The Maze, something went wrong with the 3D. At first, we thought there was a problem with the disk mastering – although that seemed unlikely, since I’d read nothing in any of the reviews of Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray. It looked as if the left- and right-eye fields had suddenly switched. The foreground was still more or less normal, but the background split into two separate images. This had the weird effect of making the foreground appear to be behind the background, as if seen through a gap in the background image. All extremely disorienting.

When we stopped the disk, Steve’s TV immediately went into update mode for some reason and we tried again when it rebooted … and this time everything was normal. The more complicated technology (the physical TV and the digital media) gets, the more mysterious it is to me …

*

Both disks – Shout! Factory’s The Deadly Mantis and Kino Lorber’s The Maze – offer what is probably the best viewing experience these low budget features have ever had, in any format. Mantis, scanned in 2K, is predictably uneven given the various sources of stock footage used and the many optical effects combining miniatures and live action. But the 4K restoration of The Maze’s 3D image is superb; the sense of depth and the rendering of contrast and detail seem flawless.

Tom Weaver provides a lot of historical and critical information on each disk – joined on Mantis by David Schecter and on The Maze by Schecter, 3D specialist Bob Fermanek, and Dr. Robert J. Kiss. As already mentioned, Mantis also features the MST3K episode, while The Maze includes an interview with Veronica Hurst and a restoration of the original three-channel stereo soundtrack.

Comments

I’ve enjoyed both of those movies in the past and suspect I’ll enjoy them again someday. I don’t think I’ll pick up the Blu-rays, other things clamor for my cash, but who knows, maybe they’ll turn up on sale somewhere cheap. Always something to buy. I usually like hearing a Tom Weaver commentary, another selling point.

I’m a sucker for these ’50s movies. Picked up the Blu-ray of Jack Arnold’s Tarantula yesterday – with another Tom Weaver commentary.

I have upgraded several of the older SF films from the 50s to Blu-Ray. The Thing (1951) was a recent purchase and I am looking forward to the Blu-ray of The Monolith Monsters coming from Shout Factory. That’s one of my favorite of the era.

I love Monolith Monsters … one of my all-time favourite ’50s sci-fi movies since the first time I saw it on TV back in the ’70s.

So DO LOVE to find folks out there with such a passion for the 1950s Sci Fi Genre. From an early age i was smitten growing up in the 60s watching re runs on TV in the Uk of classics such as ‘The Day the Earth stood Still’ and ‘The Thing from another World’. During the 80s i was introduced to the Bible of the subject namely Bill Warren’s’Keep watching the Skies’. A book that re ignited my latent passion and got me looking out for so many more movies, firstly on VHS then ultimately , like yourselves, DVD and Blu Ray. Keep Lookin!!

Warren’s book is pure gold … despite all the information available on the Internet, I still refer to it when I come across obscure movies from the ’50s.