Blu-ray Review: Things to Come (1936)

While it’s quite common to like a movie despite its flaws, it’s also possible to appreciate a film in spite of its content. Griffith’s technical achievement can be admired even as we are appalled by the racist politics of Birth of a Nation; we can recognize the visual beauty of Riefenstahl’s use of camera and editing to create fascinating abstract patterns of movement in her Nazi-commissioned “documentaries” Triumph of the Will and Olympia. And we have embraced Fritz Lang’s Metropolis as an imaginative achievement despite the absurd terms of its allegory of Labour and Capital.

Although it has never attained the wide prestige of Lang’s film, H.G. Wells’ Things to Come (the on-screen title) has long been a favourite of science fiction fans. It’s a fascinating – and fascinatingly flawed – work whose production circumstances are almost unique in the history of cinema. By the 1930s, Wells was a major public figure whose work had moved far away from the early scientific romances which first made his name. He was a committed socialist whose later writings were highly polemical in their mission to bring about an end to the idea of individualism and its dangerous extension, nationalism.

As Wells approached the age of 70, producer Alexander Korda offered him a remarkable opportunity: Korda would put all the resources of his production company, London Films, at Wells’ disposal, giving the writer complete control over any project of his choosing. Instead of adapting one of his more popular novels, Wells decided to turn his recent “future history” The Shape of Things to Come into a vast propaganda film advocating the end of nation-states and the establishment of a single world government run on his particular brand of socialism. (Wells admired the Russian Revolution, but felt that it had been less effective than it should have been because of the lip-service it paid to Karl Marx’s idea of a proletarian state; Wells didn’t think the working class had the intelligence or abilities to run the state, that rather the workers must always be subordinate to a ruling class of intellectuals and managers.)

Given Wells’ complete lack of experience with filmmaking, the project was in trouble from the start. He wrote a huge unwieldy script which would be very difficult to visualize and part of his agreement was that no one could change a word of it. Given its ambition, much of the production’s emphasis was put on the design – the film would cover a hundred years and depict the destruction of the world as we know it and the rebuilding of a new world. Korda brought in the renowned production designer William Cameron Menzies as director, although apart from a handful of co-directing credits, he had no taste for directing actors or even for telling a story. Along with Menzies and designer Vincent Korda, many other prominent people came and went – famous artists and architects – some of whom were discarded and some of whom walked away because they disagreed with Wells’ ideas. In the end, the remarkable look of the film was largely the work of Menzies and Korda.

It’s the design of Things to Come which has made it a lasting favourite, as ambitious and visually powerful as Metropolis. But Wells’ script remained problematic as both drama and polemic. Constructed in three major movements (the symphonic structure was deliberate and composer Arthur Bliss was integral to the project even before filming began), it begins with what seems like a very prescient depiction of the world war which was just a few years in the future at the time of production. The aerial bombing of Everytown looks now very much like newsreels from the Blitz of 1941-2. But while we know that the destruction of the Second World War was accompanied by an explosion of technical advancement (not just in sophisticated weaponry, but also in the electronics which eventually gave us computers and smart phones) which resulted in decades of prosperity, for Wells’ purposes the war (which lasts almost thirty years in the film) destroys society, pushing it back to feudal times.

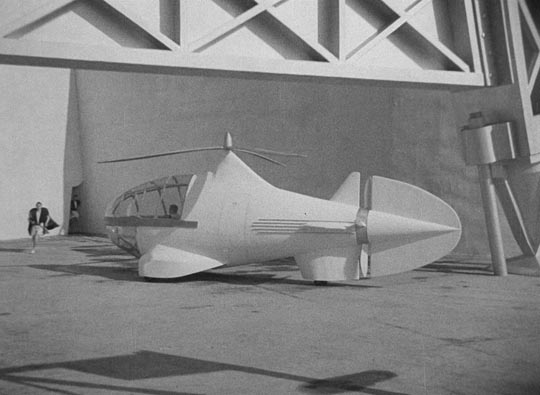

In the film’s mid-section, Everytown is still in ruins, ruled by a petty dictator called the Boss, who spends his time warring with a neighbouring “state” in order to increase his own stature. As he tries to rebuild an air force so that he can bomb his enemies with gas, an envoy from the new world order – the Air Dictatorship based in Basra – arrives, much like Klaatu fifteen years later in The Day the Earth Stood Still, to present an ultimatum: disarm and submit to the rule of the world government or be crushed. After the Boss has been dealt with, the film presents a lengthy interlude depicting the reconstruction of Everytown as a fabulous underground city of the future. The effects even today are really impressive, using a combination of photographic techniques and elaborate miniatures. It’s like the greatest Flash Gordon episode ever made.

But once the city is built, it becomes apparent that Wells’ dream of the future is pretty sterile. The rulers live in their great glass towers (penetrating underground rather than rising up like the city in Metropolis), while the population – in accordance with the end of individualism – are a swarming mass down below. But even here, if for nothing else than just dramatic purposes, this future paradise needs conflict and so we get the dissident sculptor Theotocopulos who longs for the old days of messy disorganization which allowed the imagination to flower. Despising the scientific dictatorship, the artist leads a mob to try to prevent the launch of a young couple into space.

Here Wells’ misunderstanding of film as a medium becomes very clear. For symbolic reasons, he wanted a giant gun to fire the capsule towards the moon, even though it was widely known that this was scientifically impossible (the occupants of the capsule would be crushed to death instantly) and actual rockets had already been built and tested (not to mention depicted convincingly in Lang’s Frau im Mond seven years earlier). Wells wanted to illustrate the idea that the technologies used previously in wars to destroy had now been transformed into tools of progress … but film being film, a very literal medium, the image of the space gun, although an impressive miniature, can’t help but look silly.

By the final moments of Things to Come, Wells’ vision of world peace and human progress has taken on a chilling tone. The firing of the gun has coincidentally killed all the dissidents with its shockwave and Wells’ mouthpiece Oswald Cabal dismisses these puny victims as he speaks soaringly of the endless human journey which will take us as a species throughout the universe. The rhetoric disturbingly echoes Nazi propaganda about racial superiority and disdain for subhumans.

The inhuman chill which runs through the film, while motivated by a recognition of the appalling self-destructiveness of our species, completely undermines Things to Come as drama. There’s an unavoidable conflict between Wells’ vision and the basic needs of storytelling (which is why, by this time, his work no longer consisted of novels, but rather had become massive essays projecting his ideas into the future). There are essentially no characters in the film, merely types; there is no dialogue, merely speeches. The combination of these declamatory speeches and Menzies’ disinterest in directing actors pretty much left the cast to their own devices and, not surprisingly, it’s the “villains” who come off best.

Raymond Massey in the dual role of John Cabal and his grandson Oswald (problematic in itself as it inadvertently establishes the impersonal world government as a single family dynasty) displays his remarkable facility for sounding passionate and authoritative which led to his casting as great leaders in a number of films, plays and television shows. But the film really only comes to life in the mid-section with Ralph Richardson tearing gleefully into the role of the Boss and Margaretta Scott as his chief mistress Roxana; these two come closest to being recognizably human, paradoxically making the end of the old world seem oddly disappointing rather than desirable.

But while the film is so problematic on the level of drama and even in its central ideas, which ultimately resemble the fascism which was already pushing Europe towards a new war, its visual accomplishments remain endlessly fascinating. Like Metropolis, this is one of the great imaginative feats of the cinema; we might not want to live in the world conjured up by Wells, but we love to visit it because it seems so much larger and more interesting than the one we actually live in.

Things to Come opens with a superb sustained montage which uses Eisensteinian techniques to depict the complacency of the people of Everytown, celebrating Christmas Eve in the shadow of the imminent threat of war; the radical cutting of picture and sound, driven by Bliss’ powerful score, gives what follows a sense of inevitability. When we suddenly cut to Cabal’s quiet middle class home, with him brooding over the evening headlines, we’ve been primed to accept his interpretation of the situation and, by extension, the solutions he will eventually offer as head of the Air Dictatorship. In this way, the film manages to make Wells’ arguments more forcefully than the interminable speeches.

If the film does come anywhere near close to making an argument for the end of nation states and the establishment of a unified world based on reason, it’s through its design, its mise en scene, the energy of its editing and the dynamism of its photography. All of which makes it frustrating in retrospect that Wells’ was so vehemently opposed to anyone helping to shape the script. Here, then, the primary creator was also the finished film’s greatest hindrance. And we fans are enthralled despite the intentions of Wells, and appreciate the film for its depiction of an imaginary world rather than for the arguments it was intended to convey.

*

The disk

Things to Come has been a “partially lost” film since the moment of its release. It was initially submitted to the British Board of Film Censors in a 117-minute cut, but was quickly shortened, first to 113 minutes, then down to 97. In North America, it was most widely seen in a 93-minute cut. Although the published script reveals that most of what was taken out was more speechifying by Wells’ various mouthpieces, the cuts have left odd scars in the film, strange lapses in continuity with some moments apparently moved to different places in the narrative. Criterion’s new Blu-ray edition presents the same 97-minute cut that was released on region 2 DVD by Network in 2007. The 4K transfer from the BFI’s fine-grain composite print is some generations from the original negative, with surface scratches visible throughout and slight fluctuations in contrast. Given that no original negative is ever likely to show up, this is probably the best we’ll ever see it.

More problematic is the mono soundtrack, also taken from that 35mm composite print. For much of the film, the dialogue is muffled and difficult to make out clearly, although Bliss’s music comes through strongly.

The extras

The most significant supplement is a typically lively and informative commentary track by David Kalat, who fills in a lot of the background of the production: Wells’ intentions, the strange arrangement he had with Korda and the conflicts which resulted from it, the various elements of the creative team which resulted in the impressive visuals, and jarring continuity errors resulting from pre- and post-release cuts.

Cultural historian Christopher Frayling provides a 23-minute visual essay on the film’s design, and Bruce Eder delivers a 16 1/2-minute analysis of Arthur Bliss’ score, pointing out the ways in which the use of the music differs from standard techniques of film scoring at the time. There are four minutes of experimental images created by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, who was hired briefly to create montage elements, some of which ended up in the reconstruction-of-Everytown sequence. Finally there’s an audio recording from 1936 of a passage from the script about the Wandering Sickness, the plague which killed off half the population in the wake of the war, and the usual Criterion booklet containing a helpful essay, this time from Geoffrey O’Brien.

Comments

I much prefer the Network DVD’s “Virtual Extended Edition that adds intertitle cards throughout the film to show scenes and dialogue that were in the final script and were probably once a part of the film.” (1) The improvement in the narrative (for me) outweighs the choppiness of the flow, and it does not feel like the butt-numbing “whopping 134 minutes” that it is.

(1) DVD Savant quote http://www.dvdtalk.com/dvdsavant/s193things.html)

The Network edition is definitely useful in giving some idea of what the original full-length version might have been like, but it’s undeniable that most of the cuts were rather tedious exchanges of didactic dialogue, particularly leading up to the climax at the space gun. The most interesting aspect of the deletions is the surprisingly sexist view of women, the idea of their being rooted in their bodies and emotions, governed by sex rather than intellect; this coming from such a supposedly progressive writer! … but Wells had throughout his life been quite the womanizer and regardless of his progressive politics, he seems to have viewed women more as sexual objects than intellectual equals. That said, my biggest regret about the cuts is the loss of so much of Margaretta Scott’s performance – or rather performances, as her entire second role as Oswald Cabal’s estranged wife was removed.

I have to admit that in putting together the Virtual Extended Version we still omitted two fairly lengthy sequences (the children’s party, and Cabal and Passworthy’s journey through the city in 2036). We also kept the running order of the extant footage, even though some scenes occur in a different order in the script (e.g. Theotocopulos’s speech should occur much later on).