Greg Hanec’s Think at Night (2024)

As I’ve mentioned before, it’s always difficult to write about the work of someone I know. How do you remain objective (if that’s even a thing when you’re trying to put down your personal response to something you’ve experienced) and disentangle what you know of the person from what you see in the work? Of course, it’s easier if you happen to like the film regardless of who made it; but when it’s a difficult or challenging work, I admit I have a tendency to try to tread lightly – what if I’m missing something, or misreading it? I don’t want to offend the person I’m writing about, nor do I want to make a fool of myself. None of this matters when I write about the work of someone I don’t personally know, but when there’s a risk of running into them I tend to want to keep my thoughts to myself.

This anxiety surfaces again because I’ve recently seen Greg Hanec’s Think at Night, the latest (short) feature by a local Winnipeg filmmaker whom I’ve known since the early ’90s. I’ve written about his work before – I reviewed his second feature, Tunes A Plenty (1987), for the arts journal Border Crossings at the end of 1988, before I’d met Greg; although I had some reservations, I liked the film for its gritty, underground naturalism. Later, I saw his first feature, Downtime (1985), which was notable for being the first Winnipeg feature to play at the Berlin Film Festival, and remains one of my favourite local films (I wrote about it when it was released on DVD back in 2012).

For a number of reasons, Think at Night proved to be more difficult to get my head around. What I’d liked about the previous features was their deadpan naturalism, but the new film is more abstract. In addition, my first viewing wasn’t ideal. But I’ll get to that in a moment. First, some background. Greg had started shooting the film in 1992, a few years after Tunes A Plenty. He worked on it fitfully during the ’90s, improvising scenes and editing each one before coming up with the next. But being something of a creative polymath, he focused more on his music, painting and photography. At the end of the decade, looking at what he had done so far (roughly the first twenty minutes), he decided there was definitely something there and resumed the process, shooting additional material into the early ’00s.

And then the long labour of completion stretched out for years. I’d occasionally run into Greg during those years and ask when I’d be able to see the film and he’d always say he was working on it and hoped he’d have a cut in a few months. His procrastination cast an air of absurdist comedy over what had become a mythical cinematic creature, so I was both surprised and excited when I heard that Think at Night would finally premiere at the Kinoskop Analog Experimental Film Festival in Belgrade in December 2024. It had another screening in the Yukon before finally landing in Winnipeg for a local premiere at the Dave Barber Cinematheque on June 8 during the Winnipeg Underground Film Festival.

The decades-long wait definitely raised my expectations, but that screening to a full house wasn’t entirely satisfying. Part of the problem was that Greg’s film, which like Downtime runs only 62 minutes, was preceded by an 18-minute short of a kind which irritates me – a seemingly random collection of found and original footage which seems to have been dumped out of a trims bin in the editing room and strung together with no sense of rhythm or structure – so when Think at Night began I wasn’t in the best, or most receptive, mood. This wasn’t helpful, because the film is aggressively abrasive, particularly in its first half.

It might have been my mood or the acoustics in the theatre, but during that opening section all I could hear was what seemed like an industrial roar trying to push me out of the movie – there were a couple of walkouts – but then a scene caught my attention, and then another, and the rest of the movie became more engaging because it echoed those qualities I’d appreciated in Greg’s first two features, an attention to the mundane details of undramatic lives delivered with a very dry, deadpan comedic edge. It had taken me a while, but I was finally drawn in and increasingly liked what I was seeing, and I was eventually surprised to find myself moved considerably by the final scene.

The best part of the screening for me was actually the Q&A which followed, during which Greg was articulate (and somewhat self-effacing) about the thirty-plus year process of completing the film. Later that evening, we had a long text exchange about Think at Night, during which he was open to my reservations (though surprised at some of my comments, particularly about the “noise” during the opening sequences, which he referred to as music). We agreed to meet for coffee a few days later to continue the discussion, which we did, beginning with the film itself but then ranging over numerous other topics for three-and-a-half hours – much longer than any conversation we’d previously had.

And, perhaps most importantly, he sent me a link to an online copy of the film so I could watch it again and explore my reaction in more depth. In fact, I’ve watched it twice more and found more to like in it on each viewing, with certain cryptic elements becoming clearer the more familiar I am with the overall context. It’s a more difficult film than Downtime or Tunes A Plenty, certainly, but I find myself drawn back to crack its codes and prise out additional details – and on each viewing I find that final scene more deeply moving.

*

My initially unreceptive mood at the Cinematheque screening was obviously a problem, but the film itself takes big risks with alienating its audience. My first impression was of a string of disconnected scenes whose meaning is often cryptic, delivered in a style which challenges the viewer to keep watching. After a lingering opening shot of the shimmering surface of the Assiniboine River, a series of shots show the flow of traffic on city streets. We eventually see the figure of a woman approaching off the Arlington Street bridge; coming closer, she stops at a pay phone (the first clear indication that Think at Night is now a “period piece”). She dials and there’s a cut to a hand lifting a receiver and letting it drop without responding. Another cut reveals a naked man sitting at a kitchen table by the phone, lighting a cigarette. We don’t get any information about these people and it’s difficult to interpret anything we’ve seen because of a heavy layer of non-diegetic sound – what seemed to me at the time to be an arbitrary roar of industrial noise.

When I spoke about this to Greg, he seemed puzzled, referring to the sound as music. My impression changed drastically the first time I watched the film at home; this “noise” did in fact resolve into music, a distorted and speed-adjusted tape loop somewhat reminiscent of experimental composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen, John Cage or Glenn Branca, who push their listeners to discover the structures underlying what initially sounds like chaos.

The sense of randomness continues through a series of scenes in which the man we’ve seen embarks on a night of wandering and encounters with friends and acquaintances; again, the meaning of these meetings is seldom immediately apparent, although what we learn in fragments during later scenes does reflect back and make things a little clearer. Throughout the first half in particular, the film addresses its audience with a challenging aggression; you’ll have to watch it more than once to make sense of what’s happening.

In addition to the abrasive use of sound, the camera technique in many scenes is equally alienating. During a meeting with two other men in a coffee shop, Al’s irritable comments are amplified by numerous micro-jump cuts, while the characters’ conversation fights against the ambient noise of clattering dishes and background voices. A party scene is shot with an uninterrupted circular pan which refuses to settle on various small groups whose conversations we hear in fragments as they pass quickly in and out of view. This devolves into a kind of “happening”, where a film loop is projected on a wall where someone stands as someone else takes photographs, again shot with a circling camera, but now with other layers added to the image, including glimpses of some desultory flagellation and a medium closeup of a woman reading a kind of manifesto which mentions the negative consequences of fear and distrust, all weighed down by an oppressive blanket of musique concrète.

This sequence marks a transition point, the disjointed and chaotic barrage of image and sound giving way to a series of dramatic scenes involving Al (played by Hanec himself) and two particular acquaintances, Stuart (David Stubel) and Dana (Alerry Lavitt). But even here, while the camera settles into a more observational, naturalistic style, a number of scenes are shot in dark spaces with the lens aimed directly at bright light sources, creating flares and reducing the characters to barely glimpsed silhouettes, as if the film simply can’t resist scratching at the viewer’s eyes. If the first half challenges the audience to keep watching, the second half seems to promise an accessible narrative and some kind of revelation – something which, in retrospect, it does provide, although obliquely.

There are two main themes running through the film, though it’s up to the viewer to piece together the clues from which they emerge. While it’s obvious that Al is alienated and in a constant state of irritation which occasionally spills over into anger, the roots of his existential condition are revealed piecemeal. One thread is purely material; he has little money and bills to pay, though he openly disdains work. In the coffee shop scene, he tries to get back some money he lent one of his friends, but ends up being asked to lend the guy some more. He mocks his other friend for having taken a job, even though the guy needs money to replace his broken-down recording equipment. The second thread is also introduced in this scene; both friends are musicians, even this day job being taken only to finance creative endeavours.

Although we never actually learn why, it becomes apparent that Al has given up his own creative work. Yet everyone he knows is working on something and the conflict this produces in him is what spills out into the film’s style; his mind is in turmoil, oppressed by what he seems to tell himself is futile and pretentious work – every encounter is a reminder of what he has rejected, a rebuke of his determination to see all art as a waste of time.

Certain encounters seem to confirm his opinion. Between the coffee shop and party scenes, he pays a lengthy visit to another friend (Tom Kohut) who’s working the night shift in some kind of medical lab. As the camera tracks with them through a maze of fluorescent-lit corridors, the friend insists on reading a long poem he’s written. Al is incapable of concealing his boredom and disinterest, but his friend is undeterred. As they walk and walk, he keeps reading and the film itself (like Al and the audience) eventually zones out and the droning voice is layered over itself, the words fighting one another to penetrate his (our) indifference. Eventually the camera drifts away from the pair and tracks past lab benches laden with various pieces of equipment, as if trying to find something more interesting to look at.

And yet the poem gradually takes on increasing significance after Al meets up with Stuart. At odd moments, Stuart takes papers from his pocket and begins reading the poem aloud. When Al objects, Stuart explains that he has to memorize it because he’ll be reciting it at some event in a couple of weeks. Later, the same thing happens when he begins to read the poem again in front of Dana; when she grabs the papers and crumples them, Stuart continues to recite to her, but now from memory. The poem will return once again, in the final sequence, taking on an unexpected significance as it comments on the film itself and on Al and Dana’s disdain for art.

But before that point is reached, money rears its head a few more times. When Al meets Stuart (in an underground movie theatre – Al: “what’s showing?”, Stuart: “the same old shit”), although we have no idea what Stuart’s particular creative practice is, he tells Al that he’s “turned down the commission, but agreed to a retrospective” because he needs the money. Then he mentions that someone who owes Al money is in a nearby room. This is Gary (Mike Maryniuk), a filmmaker who has received a grant to recreate some classic experimental films – right now he’s duplicating “John Lerner’s 9”, a nine-minute static shot of a 16mm camera recording itself in a mirror. Gary proudly explains that they managed to obtain the exact same film stock as the original filmmaker back in 1969, so he’s able to duplicate the original film’s grain structure. This sequence was shot on short ends retrieved from a freezer and the stock used has the thickest, most active grain structure imaginable, transforming the dimly lit scene into a hypnotically liquid abstract image which belies the satirical intention of the scene; while Gary’s project seems pretentiously introspective, the physical quality of the image itself has a strange, inherent beauty.

But the dramatic purpose of the scene revolves around money; Al wants back the $25 he lent Gary several years ago. But Gary only has two $20s. Al suggests he should be given both and owe Gary $15 in return; after an irritable exchange, they agree that Gary will give him one $20 and still owe him $5. The pettiness of this haggling reflects strangely on the subsequent sequence in which Al and Stuart visit Dana, prompted by a call from her offering to repay Stuart for a loan. The amounts here are considerably higher; he had loaned her $1500 and she tosses him a bundle of $50s totally $2000. When Stuart protests, she says consider it interest, then tosses him another bundle. Then she tosses a bundle to Al, who immediately throws it back, initiating an odd game of catch, with both Al and Dana apparently wanting to get rid of the money. When Stuart asks what’s going on, Dana replies without elaboration that “it was Al’s idea”.

We only learn later that the money had come from a project Dana had done, during which she had almost died – although everyone in this world needs money, either to create their art or just to live, for both Dana and Al, this money in particular seems to be tainted by its origins. Like Al, Dana has given up her own artistic practice and wants to distance herself from it by getting rid of the money she earned. We never do learn why Al has given up, but Dana’s traumatic experience suggests that the act of creation is inextricably woven into the fabric of an artist’s life, not something separate and outside, and it can reflect back negatively on the creator.

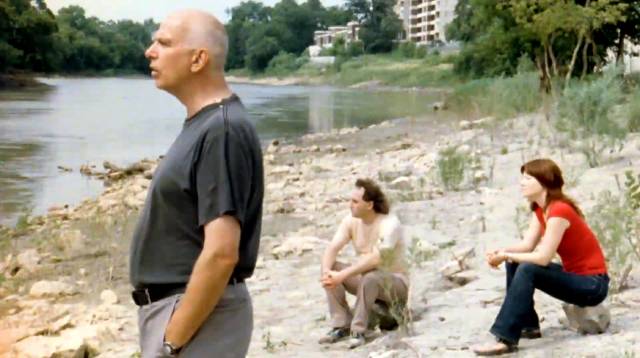

And yet the creative impulse can’t be suppressed or denied, no matter how much an individual might want to be free of it. At dawn, Al splits, saying he’s going down to the river, while Stuart and Dana go for breakfast – it’s in the diner that Dana finally recounts her near-death art experience, after crumpling the pages of the poem Stuart is memorizing. Then, after eating, Stuart and Dana split; she makes her way to the river where Al is sitting on a rock staring at the water, his back to the concrete holding the bank together beneath towering apartment blocks.

After a brief exchange, he and Dana sit in silence, together yet separate, and eventually Stuart arrives, stands at the water’s edge, and begins a perfect recitation of the poem – but now it’s different; the droning soup of words we heard at first in the lab scene, and later in hesitant snatches as Stuart was trying to commit them to memory, are suddenly full of meaning and emotion, stitching together everything we’ve seen, art shaping and binding the random fragments of experience which have brought the three characters to this place, away from the noise and distraction of the city. Here by the water, among sounds of birds and the river itself, all the noise and agitation which have been driving the characters (and the viewer) to distraction fall away and the poem, so eloquently spoken now by Stuart, make clear what lies behind everything we’ve seen and heard through this long, uncomfortable night:

“the whirl of words and ideas, emotion/now we have you walking, thinking you are invisible/well, you are/but the path is marked/I’ve never done anything out of the blue/just as well/spontaneity has been marked out within certain seemingly unavoidable parameters/abnegation of the will to escape guilt/but you will not escape … ever/through the park gates, through the pillars of sound, the empty streets, the empty seas/we are you, you are one of us/no matter how much you protest/all of you, they, watch out, get out for heaven’s sake/leave, end this absurd sequence/… I can’t”

Comments