Viewing notes: June 2017 – Arrow Video

I wrote a couple of weeks ago about the problem of my disk backlog. There’s a real psychological pressure exerted by those shelves of unwatched disks, particularly as most of them were purchased because of a genuine interest in the movies they contain (I say most, because there’s also a degree of impulse buying disconnected from what I like to think of as my serious interest in film art and history). In that post, I focused on Twilight Time, but I have an even bigger problem with another of my favourite labels: Arrow Video.

I’ve written before about the impressive range and variety of Arrow’s releases – they have a substantial catalogue of genre titles, but also an on-going commitment to film art. So many desirable releases, and so many of them big sets which require a lot of time to do them justice, which is hard to accommodate around the demands of a full-time job and the routines of daily life. Some of these multi-disk sets are simply daunting: Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Dekalog (9 1/2 hours plus lots of extras); Kiju Yoshida’s Love + Anarchism (10 hours plus extras); the Jacques Rivette Collection (I’ve wanted to see Out 1 for years, but the desire to watch the whole 12+ hours in a short, concentrated timespan makes it almost impossible to fit into my schedule; the rest of the movies in the set run to another 11+ hours, with additional hours of extras as well); the three film collection by the Taviani Brothers (7 hours plus extras). I’ve recently also bought the new deluxe edition of Dario Argento’s Phenomena (containing all three versions of the movie, plus a feature-length making-of documentary), the six film Outlaw Gangster VIP set (9 hours plus extras; of interest as a precursor to Kinji Fukasaku’s masterpiece, Battles Without Honour and Humanity), and Takashi Miike’s Black Society Trilogy (5 hours plus extras).

And beyond these imposing multi-disk sets, there are quite a few individual movies – some previously unseen, but many Blu-ray upgrades of favourites: Jack Hill’s Spider Baby, Peter Fonda’s The Hired Hand, Ken Russell’s Crimes of Passion, the restored edition of Wes Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes, Andrzej Zulawski’s final film Cosmos, Elio Petri’s Property Is No Longer Theft, Walerian Borowczyk’s Story of Sin, Sam Peckinpah’s Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (duplicating the excellent Twilight Time release, but with substantial extras exclusive to Arrow’s edition, including a commentary by Stephen Prince, Paul Joyce’s feature-length documentary Sam Peckinpah: Man of Iron, and most remarkably a separate disk containing the complete unedited interviews Joyce conducted for the documentary with 19 of Peckinpah’s collaborators – some ten hours of material). Then there’s Tonino Valerii’s western Day of Anger, Ulli Lommel’s Tenderness of Wolves, Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist, and Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko. Some of these have been sitting on the shelf for a long time now, nagging at me.

But the only ones I’ve watched recently, in addition to Mario Bava and Riccardo Freda’s Caltiki: The Immortal Monster, are Emilio P. Miraglia’s pair of gialli packaged together as Killer Dames, the five Stray Cat Rock movies starring Meiko Kaji, the complete Phantasm set, and J.P. Simon’s adaptation of Shaun Hutson’s pulp novel Slugs. While I enjoyed all of these to some degree, I can’t help but feel a bit guilty about giving them precedence over the more “serious” disks I continue to neglect.

Stray Cat Rock

(Yasuharu Hasebe/Toshiya Fujita, 1970-71)

Although these five Meiko Kaji movies are lumped together under that Stray Cat Rock umbrella, they aren’t actually a coherent series. Kaji plays a different character in each film, while other cast members turn up in different roles across the series. Three of them were directed by Yasuharu Hasebe – Delinquent Girl Boss, Sex Hunter, Machine Animal; the other two by Yoshiya Fujita – Wild Jumbo, Beat ’71; and they were made and released quickly over eight months from May 1970 to January ’71. What they have in common is an attitude. Essentially updating ’50s Hollywood biker and juvenile delinquent movies to a Japanese milieu, they have an abrasive punk sensibility driven by rapid-fire editing and jazz/rock-inflected scores. And, centred on the various characters played by Meiko Kaji (Lady Snowblood, Female Convict Scorpion), they play with generic gender attitudes which upend the macho posing of yakuza movies. This suggests that the series may well have had an influence on Jack Hill, whose Switchblade Sisters, made four years later, shares certain similarities.

The series features strong, tough women who confront male oppression and violence, sometimes successfully, sometimes with tragic results. These pulp narratives are set against then-current political events – particularly student revolt against Japanese collaboration with the U.S. during the Vietnam war. There’s an undisguised fascist element in some of the male-dominated gangs, aligning organized crime with the political establishment.

In addition to confronting gender issues, the series also deals explicitly with Japanese racial and ethnic prejudices. Japanese culture has long clung to ideas about racial purity, so mixed race people pose a challenge – or affront – to the establishment. In the first film of the series, Delinquent Girl Boss, the lead character Ako is played by Japanese-Korean singer Akiko Wada, an outsider who carries a great deal of self-assurance, while the central thread of the third film, Sex Hunter, deals with the quest of a bitter half-Japanese man (Rikiya Yasuoka) searching for his half sister in a town controlled by a gang of racist thugs.

While hardly art, these five movies are energetic and entertaining, the Japanese background adding interest to the biker/juvenile delinquent genre tropes.

*

Phantasm I-V (Don Coscarelli/David Hartman, 1979-2016)

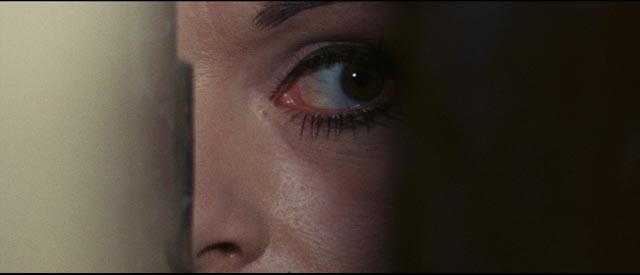

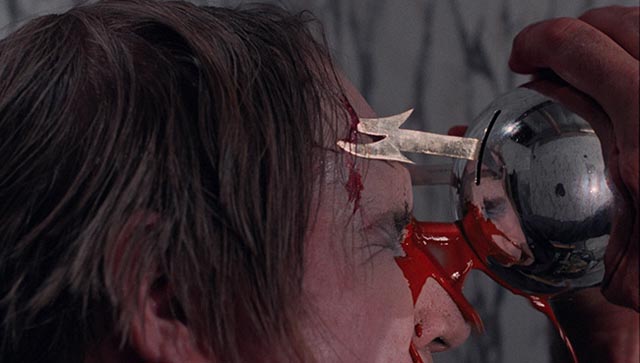

There are also five movies in the Phantasm series, but that’s where the similarities end. Instead of being filmed and released in less than a year, Don Coscarelli’s strange, imaginative world-building series spans thirty-seven years. And except for one glitch in the first sequel, the same actors appear in every episode portraying the characters they created in the first film in 1979. (That glitch was imposed by Universal, which financed Phantasm II; for some reason they were okay with Coscarelli’s stock company except for A. Michael Baldwin, who plays Mike, insisting that he be replaced by James LeGros, whom I assume they considered destined for stardom.) Perhaps most remarkable is the consistency of tone which is sustained across the series as those characters grow older and more battered, clinging to their friendship as their lives are consumed in a never-ending conflict with death as personified by the Tall Man (Angus Scrimm).

The first film is a dreamlike study of an adolescent boy trying to come to terms with the death of his parents and the fear of losing his older brother. Coscarelli establishes the narrative ambiguities which grow more elaborate and complex as the series developed: there is no clear delineation between subjective and objective, between a familiar reality and a bizarre alternate existence in which the alien nemesis invades the world of Mike, his older brother Jody (Bill Thornbury) and their friend, ice cream man Reggie (Reggie Bannister). The Tall Man dominates the local cemetery and mausoleum as he compresses the dead into reanimated dwarves which he sends to a parallel dimension to serve as slaves on a burning, heavy-gravity planet.

As bizarre as the underlying concept is, it remains grounded in the psychology of the central character; the horrors may well embody an elaborate fantasy conjured by Mike in an attempt to contain and control the emotional pain connected to the death of his parents. In fact, beneath the bizarre surface details, the underlying theme of the series deals with Mike first facing the horror of death’s inevitability and then learning to live life with that awareness of mortality always in mind. Coscarelli manages to maintain the balance between this explanation and the alternative – that the Tall Man is objectively real – to the end. As the series unfolds, the characters’ psychological states are inextricably interwoven with what appear to be objectively real alternate realities – until in the fifth film, Phantasm: Ravager (produced and co-written by Coscarelli, but directed by David Hartman) all distinctions break down as Reggie (like Billy Pilgrim in Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five) becomes unstuck in time and space, helplessly and rapidly moving from one reality to another, unable to discover which, if any, is his “real” reality … and clinging to the idea of the Tall Man’s world-destroying apocalypse as a paradoxically preferable alternative to the lingering dissolution of dementia.

From Phantasm II on, the series becomes increasingly apocalyptic, and yet it remains stubbornly personal. The Tall Man is emptying out our world to supply those slaves to another dimension, but it’s not clear that anyone but our main characters are aware of what’s happening – people they encounter along the way do comment about ghost towns, but attribute them to “people moving away”. As many of the people Mike and Reggie encounter either die at the hands of the Tall Man’s minions and deadly sentinel spheres or turn out to be his agents, the world seems pretty much limited to the handful of main characters. This dichotomy – the tightly focused personal set against the increasingly epic apocalypse – gives the series its distinctively disorienting tone.

The five films play many variations on the themes established in Phantasm, but the repetitions don’t suggest any imaginative failure – they emphasize the overall quality of a dream, of dreamers trapped in a loop where they are forced to confront unresolved fears over and over again, this lack of resolution gradually intensifying the repetitions until the characters’ grip on sanity begins to disintegrate. This process is amplified by watching all five films in rapid succession (I watched them over two days), as the aging of the actors is accelerated. Whether consciously intended or not, the series shows the toll life takes on these characters, a melancholy awareness of mortality given resonance by intercutting imagery from the earlier films into the later ones – seeing A. Michael Baldwin change from that skinny adolescent into a sad-eyed, sympathetic middle-aged man accomplishes something similar to what Richard Linklater was going for in Boyhood, a visual record of the subtle evolution of an individual over time; of course, in this case we read the signs of time’s passage in Baldwin’s features as a consequence of a life spent fighting an endless battle against the Tall Man’s evil. It’s a real thrill in the fourth film, Phantasm: OblIVion (1998), to see entire scenes shot two decades earlier, but not used in the original film. These provide an expanded sense of the characters’ history which mere flashbacks never could.

Arrow’s Limited Edition set comes in a box with a replica of one of the sentinel spheres and hours of extras, including an amiable commentary on each episode and numerous new and archival documentaries and featurettes. You come away with the impression that these are some of the greatest hand-crafted home movies ever made, their production an integral part of all the participants’ lives. But what really counts is the terrific restorations, which look great on Blu-ray. This was always a relatively low budget series, but each film was shot with care, the extensive night photography rich in atmospheric shadows and telling details. While Coscarelli was good with his actors in the first film (which he wrote, directed, photographed and edited when he was only 24), the core players grow with each repetition of their characters. It’s interesting that Reggie ends up being the main protagonist, a bit of a doofus (in the midst of apocalypse, he tends to focus on trying to get into the pants of every woman he meets – which never ends well), suggesting that Reggie Bannister is something of an alter-ego for Coscarelli, an ordinary guy caught on the fringes of that great fight between good and evil. Mike and Jody are closer to the centre of the fight, but their deeper involvement perhaps makes them seem less viable as audience identification figures. This helps to give the films their modest charm, something which would no doubt be absent if they focused on more heroic figures.

I’ve been a fan of Don Coscarelli’s work since I first saw Phantasm thirty-eight years ago. I was a bit disappointed that he didn’t direct the most recent film, though David Hartman manages quite well to sustain the series’ particular qualities. This set will have to sustain me until Coscarelli completes his proposed Bubba Ho-Tep sequel, Bubba Nosferatu: Curse of the She-Vampires.

*

Killer Dames (Emilio P. Miraglia, 1971/1972)

Emilio P. Miraglia had a brief career as a director – six movies over five years – preceded by almost two decades as a script supervisor and assistant director. Those six features include three apparently undistinguished thrillers and a spaghetti western, but the ones he’s remembered for a pair of Gothic-inflected gialli made back-to-back in the early ’70s. The Arrow Killer Dames limited edition set (just 3000 copies) is a hi-def upgrade from No Shame’s 2006 limited edition DVD set, which came with a Red Queen action figure complete with bloody knife (my copy is #890 of 7000). The new 2K scans of both films look excellent and come with both Italian (preferred) and English soundtracks, commentaries, and new and archival featurettes (some of the latter ported over from the No Shame set).

Although the giallo was rooted in the ’60s, particularly Mario Bava’s The Girl Who Knew Too Much, the segment of I tre volti della paura (Black Sabbath) called “The Telephone”, and Sei donne per l’assassino (Blood and Black Lace), the genre became more fully defined by Dario Argento’s “animal trilogy” of 1970-71 (The Bird With the Crystal Plumage, The Cat O’Nine Tails, Four Flies on Grey Velvet) which were made just a year before Miraglia’s The Night Evelyn Came Out of the Grave and The Red Queen Kills Seven Times, so it’s possibly a stretch to say that the latter deviated from established genre forms; rather, Miraglia’s pair emerged in parallel, combining some of the elements which would become more familiar over the next few years with other elements drawn from the Gothic tradition. This hybrid quality is probably more apparent to us now than it would have been at the time of their release.

What these two movies do have in common with so many gialli is convoluted narratives, which ultimately don’t make a lot of sense, involving derangement rooted in previous trauma, violent obsessions, madness and murders committed by figures whose identity is obscured, all presented with a visual style which frequently privileges voyeurism and fetishism.

In The Night Evelyn Came Out of the Grave (1971), Lord Alan Cunningham (Anthony Steffen) suffers from a madness rooted in betrayal by his now-dead wife Evelyn (there are repeated flashbacks to her naked tryst with somebody in the castle grounds). Cunningham, returned home to his estate from an asylum, prowls bars in a neighbouring town looking for red-heads who remind him of the late Evelyn; and once he gets them home, he takes them to a well-equipped torture chamber where he binds them and whips them. These sessions are observed by a shadowy figure and culminate in black-outs; when Cunningham comes to, he has no memory of what happened, but the women are dead. It appears that Cunningham is caught in a repetitive syndrome which demands that he keep punishing Evelyn; his therapist’s solution is for him to marry again … which doesn’t make a lot of sense, but does pave the way for plot complications.

After he marries Gladys (Marina Malfatti), it seems that the ghost of Evelyn begins to haunt the castle. More murders ensue, but even when a supposedly rational solution emerges, nothing is clear. Even knowing the ending doesn’t help to make sense of things when you re-watch the film. Who exactly are the voyeuristic observers of Lord Cunningham’s perverse games? Who actually killed Aunt Agatha? Even by typical giallo standards, the narrative is really confusing, but Miraglia invests the movie with some visual style – the art direction is as deranged as the story, with Cunningham inhabiting an absurdly “modern” bachelor pad in his castle to which the dungeon torture chamber is attached.

Although Steffen makes for a rather dull and thoroughly unsympathetic protagonist, Malfatti and Erika Blanc both give effective performances, and the faux English setting is amusingly disorienting.

The follow-up film, The Red Queen Kills Seven Times (1972), may not make much more sense, but it’s better crafted, with more engaging characters. Here, the madness and murders are rooted in childhood trauma and a reputed family curse. This hearkens back a couple of hundred years to the story of a pair of sisters, one good and one evil, with the evil one returning every hundred years to re-enact a series of murders which climaxes with the death of the good sister. In the present day, the curse seems to be playing out between sisters Kitty (Barbara Bouchet) and Franziska Wildenbruck (Marina Malfatti again) who had a childhood of violent sibling rivalry. Kitty is now a high fashion photographer and Franziska has apparently disappeared to the United States.

There’s a dark secret behind that disappearance and Kitty, plagued by guilt, begins to see the figure of the Red Queen who embarks on a murder spree. As in the previous movie, there’s ultimately a (very convoluted) rational explanation for the seemingly supernatural occurrences – but in this case, as implausible as that explanation is (recall the story of Oedipus and the lengths to which his father Laius went to try to avert a prophecy which those very attempts end up bringing about), it is clearly worked out and thus provides more narrative satisfaction than Evelyn.

Stylistically, there’s a nice sense of duality embedded in the film’s movement between the old, Gothic family estate (the source of the “curse”) and the ultra-modern world of high fashion within which the curse plays out. Given how much Miraglia’s control of the material had developed between the two films, it’s a pity he abandoned the genre after Red Queen, making just one more movie (the western Joe Dakota [1972]) before abandoning filmmaking altogether (although apparently he’s still alive, which would put him in his 90s today).

Although both commentary tracks are quite informative – Troy Howarth on Evelyn, Kim Newman and Alan Jones on Red Queen – they both approach the films from a conflicted point of view; while the commenters declare their affection, they tend to be somewhat dismissive and apologetic, emphasizing that these are definitely not top-of-the-line gialli. While Evelyn is undoubtedly a bit of a mess, Red Queen is an accomplished thriller and as good as many better known examples of the genre.

*

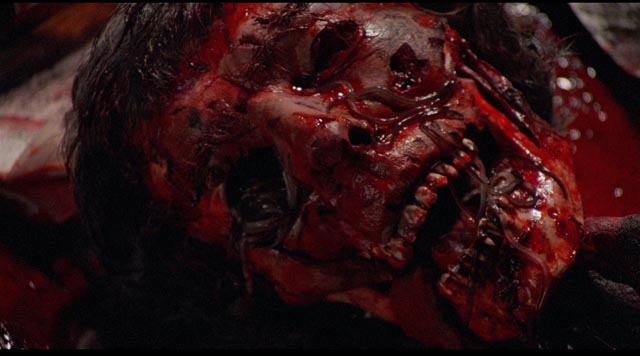

Slugs (J.P. Simon, 1988)

Shaun Hutson’s Slugs is probably the worst book I’ve ever read. No, I should correct that as I can’t say I really read it – rather, I skimmed it in about an hour. It was one of many paperback horror novels my friend Steve had acquired as research before he embarked, very systematically, on his own career as a writer of paperback horror novels (he published fourteen in eight years before switching to a career which actually paid – in advertising). He lent me Hutson’s book because he thought its sheer grossness was funny. It’s true that Hutson had a facility for describing stomach-churning scenes of people being eaten from the inside out by ravenous garden slugs, but the minimal plot and cardboard characters which served as a justification for those scenes didn’t warrant the investment of time to actually read the book.

And yet it was pretty successful, launching the author’s long and prolific career at the age of twenty-three. It was successful enough that a few years after publication the movie rights were sold. But this is where it gets kind of odd. The book has a very English setting and characters, taking place in the kind of village where everyone’s a gardener and slugs are a rather disgusting perennial pest. The script by John Gantman, however, relocates it to a small town in upstate New York … which, in itself, is a fairly predictable commercial decision. But it wasn’t bought and made by Americans. The producer was Francesca De Laurentiis, younger sister of Raffaella De Laurentiis (Conan the Barbarian, Dune and others), youngest child of Dino De Laurentiis and Sylvana Mangano; and the director was Spanish genre filmmaker Juan Piquer Simón, best known for the slasher Pieces (1982). The exteriors were shot in the town of Lyons, New York, with the rest of it done in studios in Madrid. The handful of leads were American, but most of the cast were Spanish – some of them hilariously dubbed with occasionally inappropriate voices.

Some of the movie’s strangeness no doubt resulted from the need for an on-set translator to convey Simón’s instructions to the American cast members. Whatever the reasons, even though some of the movie was shot in the U.S. it has a completely inauthentic sense of place. But none of that matters very much since, like the novel, its main reason for existing at all is the gross effects set-pieces which punctuate the unconvincing narrative which centres on the attempts of the local sewer engineer to convince the police and politicians that the town is under attack by a virulent breed of flesh-eating slugs.

Those set-pieces are actually quite impressive, with gleefully over-the-top gore effects which involve explosive vomiting in a restaurant, self-amputation in a greenhouse, and naked teenagers being smothered by a wave of slugs in the bedroom. The film’s signature moment comes when the hero squats down in the garden to take a closer look at one of the giant slugs and it opens a fang-lined mouth and bites his finger. While the human element of the movie is pretty dull, the commitment to cheese-inflected grossness is quite admirable.

Arrow’s Blu-ray looks as impressive as the movie is ever likely to, with a 2K transfer from the original negative. There are four interview featurettes – with actor Emilio Linder (he of the explosive vomit), effects master Carlo De Marchis, art director Gonzalo Gonzalo, and production manager Larry Ann Evans who provides a tour of the Lyons locations. But what makes the disk really worthwhile is a funny and engaging commentary track from none other than Shaun Hutson himself. He turns out to be pleasantly self-effacing and honest about the utilitarian nature of his writing (up to something like seventy books under multiple pseudonyms). At one point, he goes off on a very funny rant about Stephanie Meyers and the massive damage she’s done to the vampire tradition with her risible Twilight series.

Listening to this track prompted me to go back and re-watch Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace, which I always felt was inspired by Hutson (or a combination of Hutson and fellow Brit Guy N. Smith) … but the real writer lacks the pompous pretension of Matthew Holness’ Marenghi. The series nonetheless remains a wonderful parody of the kind of horror Hutson writes.[1]

I haven’t bothered to listen to the second commentary by former Fangoria editor Chris Alexander because I gave up on him a while back; he’s one of the most irritating commenters I’ve heard, more interested in amusing himself and chronically using two or three “fucks” in every sentence.

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) “… whisked off her shoes and panties in one movement, wild like an enraged shark, his bulky totem beating a seductive rhythm. Mary’s body was burning, though the room was properly air-conditioned. They tried all the positions – on top, doggy, normal. Exhausted, they collapsed onto the recently extended sofa bed.

“Then a hell beast ate them.”

– Garth Marenghi, Juggers

(return)

Comments