Year-end ruminations: 2016

It seems to get harder every year to come up with a “10 Best” or even “20 Best” list. I enjoy a huge range of movies, from the highest art to the lowest exploitation, and making firm value judgements has come to seem like a completely arbitrary exercise.

For instance, I could say these are the five films which had the most immediate impact on me in 2016:

Anomalisa (Charlie Kaufman & Duke Johnson, 2015)

Kubo & the Two Strings (Travis Knight, 2016)

Love and Friendship (Whit Stillman, 2016)

Turbo Kid (Francois Simard, Anouk Whissell, Yoann-Karl Whissell, 2015)

The Witch (Robert Eggers, 2015)

But this selection raises so many questions that I’d immediately have to begin hedging and explaining and justifying … which would in turn only lead to argument and defensiveness. I just can’t do it. So instead, I offer here a broad survey of the year’s viewing, which of necessity is rooted in what I felt like buying, often on impulse, rather than on a dutiful effort to try to see everything of quality which was released on disk during the year. That is, there are probably better and more valuable movies than most of these which I simply didn’t have an opportunity to see. It’s all subjective and I offer no apologies.

*

Once again, in 2016, predictions of the demise of Blu-ray and DVD were proved wrong. Certainly, on-line streaming has grown more popular, but the range of movies both old and new released on disk this past year indicates a very healthy market, even if it is smaller than it was a few years ago. Hopefully, it’s a matter of stabilizing in some kind of balance between platforms. One of the market mechanisms which helps to keep disk media viable is the proliferation and expansion of specialty companies which have taken over to a large degree from the major distributors – with those majors increasingly inclined to license to these smaller companies titles which they don’t want to take the trouble with themselves. So, many of my picks for this year have appeared on these “boutique” labels (I use the quotes because a number of these companies have grown pretty large over the past few years).

I’ve already written about many of these films during the year, and there’s really no way to rank them in any order, either of preference or (subjectively perceived) quality. Some are masterpieces, some obscure oddities; some may be perceived as trash, yet have distinctive qualities which make them interesting. And a few were actually released before 2016, but I only caught up with them this year. Most, if not all, have had a great deal of care lavished on them by disk producers, with excellent new transfers and useful supplements.

Criterion

The Criterion Collection had an impressive, wide-ranging slate this year, a mixture of familiar titles given impressive upgrades and less well-known titles which in some cases revealed fascinating corners of (for me, previously unexplored) film history. To pick just five at random:

A Brighter Summer Day (1991): Edward Yang’s intimate epic based on a rather pathetic murder in Taiwan offers a dense and nuanced portrait of a society whose identity is in flux – the exiled nationalist Chinese who define themselves against the monolithic power of Communist China. A haunting prose poem full of sadness and despair.

Chimes at Midnight (1965) & The Immortal Story (1968): With two superb restorations, Orson Welles is once again revealed to be very far from the failure some critics still insist on. These two films – one a huge labour of love decades in the making, the other a rich chamber piece made for French television – are not only up there with Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons; they represent the pinnacle of his artistry as writer, director and actor. His Falstaff is the greatest performance of his career and Chimes is his masterpiece. It’s well beyond time that Welles was recognized for what he achieved rather than berated for the works which were left unfinished.

McCabe & Mrs Miller (1971): Robert Altman’s finest film, an elegiac western full of humour and poetry, has never fared well on video because of the photographic techniques used by Vilmos Szigmond to create a haunting visual sense of the past. Criterion’s new hi-def transfer comes as close as possible to rendering the delicate textures of the image. This is a film of moods rather than narrative – although there is a story, about the American dream of entrepreneurial endeavour and how the individual is inevitably crushed by big business. The heart of the film is the unspoken romance between the dreamer McCabe and the pragmatist Mrs Miller, a romance which remains unfulfilled in the hard realities of the frontier.

One-Eyed Jacks (1961): Marlon Brando’s sole directorial effort is another elegiac western, this one set on the Pacific shores of Monterey rather than the wintry mountains of the Pacific Northwest. Despite numerous production problems which resulted in the producers taking it away from Brando, the film nonetheless has a strong narrative structure which works both within and against its genre; although there are moments of action, it is essentially about inaction, about waiting, about two men trapped by betrayal, guilt and a desire for revenge. Given little respect at the time of its original release, it can now be seen as a pivotal work in the evolution from the traditional myth of the west to the more critical view which developed throughout the ’60s, culminating in the genre revisionism of Peckinpah, Penn and Leone.

The Road Trilogy (1974-76): Wim Wenders was the poetic realist of the German New Wave and these three loosely connected movies from the early ’70s remain among his best and most satisfying works. The dominant theme is displacement and the need for isolated souls to find connections. The landscape is a divided Germany, a society fractured by the awful forces of history which have created a radical break in the sense of national identity. The outlook is bleak, but with touches of warmth and hope which can at times be heartbreaking.

Other notable Criterion releases this year include: Heart of a Dog (Laurie Anderson, 2015); Bitter Rice (Giuseppe De Santis, 1949); Carnival of Souls (Herk Harvey, 1962); The Emigrants & The New Land (Jan Troell, 1971-72); The Executioner (Luis Garcia Berlanga, 1963); I Knew Her Well (Antonio Pietrangeli, 1965); In a Lonely Place (Nicholas Ray, 1950); La Chienne (Jean Renoir, 1931); Lady Snowblood (Toshiya Fujita, 1973-74); Valley of the Dolls (Mark Robson, 1967).

Although it was released in 2013, Criterion’s collection of the works of Pierre Etaix was one of the highlights of my year.

BFI

The BFI continues to put out an interesting mix of high and low art, mainstream movies and more obscure titles; this year there were impressive releases from both ends of the spectrum and various points in between.

Akenfield (1974): Famed theatre director Peter Hall managed to transform Ronald Blythe’s oral history of a century in the life of a small English village into a richly layered meditation on rural life and the effects of history on tradition. Shot over the period of a year, Akenfield evokes the rhythms of country life through the 20th Century; Hall’s real achievement, attained through improvisation with a largely amateur cast, is to avoid easy nostalgia and facile romanticism. This country life has genuine charm, but it’s also often brutally difficult; the tension between tradition and continuity and the disruptions of increasingly rapid historical change is played out in the intricate intersection of individual lives and a community which stands as representative of one clear strand of the national character.

Expresso Bongo (1959): The versatile Val Guest turned from the thrillers and horror he had been making for Hammer Films to direct this musical set in London just as the city was getting ready to swing in the ’60s. The story of a manipulative agent who exploits a naive singer only to see his control weaken as the kid becomes a star may not be as cynical as Alexander Mackendrick’s The Sweet Smell of Success, but it’s definitely in the same neighbourhood. Made with pace and energy, the film is also a sharp record of Soho and the East End at the time.

Murder in the Cathedral (1951): Although the Blu-ray of George Hoellering’s adaptation of T.S. Eliot’s play about the conflict between Thomas a Beckett and King Henry II was released in 2015, I only caught up with it this year. Shot in appropriate locations, this stark historical drama is reminiscent of both Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc and Orson Welles’ Chimes at Midnight in its evocation of a Medieval world, in this case at a pivotal moment when secular political ideas began to break away from the grip of the Church.

Shooting Stars (1928): Anthony Asquith’s debut feature is a wonderfully assured work. Taking full advantage of the resources of silent cinema, Asquith created a funny yet tragic portrait of the business of making movies and the ways in which that business used and distorted and corrupted the people caught in its glamour. Full of visual wit, Shooting Stars offers a bravura display of complex multi-layered action and virtuoso camera movement, proving yet again – if proof were needed – that by the late ’20s the art of visual storytelling had attained a technical and aesthetic sophistication which, even with all the industry’s subsequent technical advances, has never been bettered.

Women in Love (1969): Ken Russell made a major breakthrough with his third theatrical feature (after a decade of innovation on television, where he virtually invented his own genre of “documentary” with a series of imaginative portraits of artists and composers). This was the film which established the flamboyant persona Russell played on and amplified throughout the ’70s, pushing against conventional ideas of good taste in order to dig more deeply into the emotional lives of his characters. With richly layered design, a free and expressive use of the camera, and performances which seem fearless and revelatory, Russell seemed florid in a way which was reminiscent of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger; like them he was willing to push things further than most other filmmakers, risking accusations of excess and hysteria, yet always in full creative control. At his best, Russell’s work is exhilarating, with an energy few other directors could come anywhere close to matching.

Other notable BFI releases: Love on the Dole (John Baxter, 1941); Beat Girl (Edmond T. Greville, 1960); Fear & The Machine That Kills Bad People (Roberto Rossellini, 1954/1952; disk released in 2015); On the Black Hill (Andrew Grieve, 1988); Psychomania (Don Sharp, 1973); Symptoms (Jose Ramon Larraz, 1974); Odds Against Tomorrow (Robert Wise, 1959); I Am Belfast (Mark Cousins, 2015).

I have also recently acquired some other BFI disks which I haven’t yet had time to watch, but which deserve mention: Culloden & The War Game (Peter Watkins, 1964/1965); Valentino (Ken Russell, 1977); and the really big release of the year, Dissent & Disruption: Alan Clarke at the BBC (1969-89), thirty-three hours of some of the most important British dramatic filmmaking of the second half of the century, which I’ve only just begun to dip into.

Arrow

This year Arrow Video has issued a stunning number of ambitious box sets, which I have been stockpiling although I simply haven’t had time to immerse myself in them yet. These include Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Dekalog (1989; it was a toss-up, but I opted for Arrow’s edition rather than Criterion’s because of the special features, in particular five other early dramatic works by Kieslowlski); The Jacques Rivette Collection, which includes both versions of the legendary Out 1 (the eight-part Noli me tangere and the shorter variant edit Spectre), plus three other features and an extensive collection of interviews and documentaries; Love + Anarchism, a collection of works by one of Japan’s most radical and political filmmakers, Kiju Yoshida; Outlaw Gangster VIP Collection, a six-film series based on the life of yakuza Goro Fujita – this is of particular interest because it prefigured the realistic depiction of yakuza life several years before Kenji Fukasaku’s epic Battles Without Honour and Humanity; and Three Films by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani which collects new restorations of Padre Padrone, The Night of the Shooting Stars and Kaos along with extensive interviews, visual essays and a commentary.

The sets I have watched so far are:

American Horror Project Vol 1, which includes three low budget features from the ’70s in the projected first part of a series intended to recover and highlight movies from the fringes; Death Walks Twice, a pair of gialli directed by Luciano Ercoli and starring Nieves Navarro (Susan Scott); Beyond the Valley of the Dolls and The Seven Minutes, a double feature comprising Russ Meyer’s two early ’70s studio financed movies, one an epic of show-biz kitsch which thumbs its nose at Hollywood, the other an awkward argument against censorship which sees Meyer working very hard to infuse energy into what is essentially a set-bound courtroom drama.

Hellraiser: The Scarlet Box, which includes the first three films in the series with a huge quantity of supplements, is an impressive set, although after the first strikingly original film – which effectively transposed Clive Barker’s distinctive fiction to the screen – the series declines quite rapidly. For the second movie, Hellbound, first-time feature director Tony Randel simply didn’t possess the obsessive attention to the physical and psychological grotesque that Barker had displayed; there are interesting design and conceptual elements in the move to the Hell-world, but the script is less focused and Randel’s handling is clumsy. In Anthony Hickox’s Hell on Earth, things get even sloppier, regurgitating echoes of Barker’s imagery while barely hanging together as a narrative. Nonetheless, Arrow has given all three films good transfers (the original is still the best-looking), and there are hours of documentaries, featurettes and commentaries which serve to treat the films as major cultural artifacts (wisely ignoring the at-least seven other sequels and numerous short offshoots). The set also includes Barker’s two early experimental films, Salome and The Forbidden.

Finally there’s Blood Bath, a thriller shot in Yugoslavia and partially financed by Roger Corman. The film itself is not particularly good, but Arrow’s edition offers a fascinating glimpse into the convoluted world of international exploitation; there are no less than four different versions of the film, shot initially as Operation Titian (1963), directed by Rados Novakovic. This rather dull story of murder and stolen art was tightened up by Corman as Portrait in Terror (1965), then repurposed the next year by Jack Hill and Stephanie Rothman as Blood Bath, in which the protagonist was changed into a vampire (or at least someone who thinks he’s a vampire); and finally elements from all three versions were tossed together for a television version called Track of the Vampire. The disk is filled out with a visual essay by Tim Lucas, who dissects the production history, and interviews with actor Sid Haig and director Jack Hill. While the movie itself doesn’t amount to much in any of its versions, it’s fascinating to see just how much effort could be put into such a trifle in an attempt to milk it for as much profit as could be squeezed from unsuspecting audiences who might be conned into paying more than once for the same material.

New acquisitions not yet viewed: Cosmos (2015), Andrzej Zulawski’s final feature, adapted from a novel by Witold Gombrowicz; Crimes of Passion (1984), Ken Russell’s outrageous thriller which plays as a kind of gloss on Psycho thanks to the presence of Anthony Perkins as a sexually repressed preacher stalking Kathleen Turner’s part-time prostitute; The Hired Hand (1971), Peter Fonda’s elegiac western; and Matinee (1993), Joe Dante’s comic homage to ’50s sci-fi B movies and Cold War paranoia.

Twilight Time

Not surprisingly, Twilight Time releases have also been stacking up this year. With four or five new releases every month, it’s impossible to keep up. The selection of titles remains very eclectic and I’ve been enticed to buy a few that I probably wouldn’t have considered in another context.

Chato’s Land (1972): Like other European emigre filmmakers before him, Michael Winner was drawn to the quintessential American myth of the western; and like many of those who preceded him, he took a critical view of the myth. Here, in his second American feature (and second western, after Lawman [1971]), working from a script by Gerald Wilson, he dissects the racist underpinnings of Manifest Destiny; the native American Chato (Charles Bronson) is identified with the harsh frontier landscape to the point of becoming an almost mystical natural force, while the European interlopers are lost physically and spiritually, their greed and arrogance becoming self-destructive.

Hawaii (1966): My impression had always been that George Roy Hill’s roadshow adaptation of part of James Michener’s fat historical novel was a misfire – surely any movie pairing Max von Sydow and Julie Andrews as a married missionary couple couldn’t be taken seriously. Turns out, it’s one of the most intelligent of Hollywood’s prestigious epic productions, maintaining an effective balance between its fraught personal drama and the historical sweep of the story of the destruction of a vibrant native culture by colonizers driven by self-righteous conviction of the superiority of their own “civilization”. The disk includes both the original roadshow version (unfortunately in standard definition) and the shorter theatrical cut; the former is a much stronger film.

The Little House (2014): This subtle, emotionally rich portrait of a middle class Japanese family before and during World War Two, was made when director Yoji Yamada was 83. Since then he has completed two more features, and is currently preparing another. Yamada had a fairly low profile in the West, partly because he was a prolific commercial director – he wrote and directed most of the forty-eight Tora-san movies between the late ’60s and mid-’90s, as well as several other series. As charming and commercially successful as many of these films were, Yamada suddenly rose to a new level in 2002 with The Twilight Samurai, a period film which ranks with the works of Mizoguchi. This was followed by two sequels, equally as good. More recently, he has turned to intimate family dramas which echo the work of Ozu Yasujiro (including a remake of Ozu’s Tokyo Story). The Little House belongs to this strand of his career and exhibits all of Yamada’s sensitivity to relationships, emotional nuance, and the interplay between individual lives and their surrounding social context.

A Prayer for the Dying (1987): After a decade-and-a-half of very uneven work following his brilliant debut feature (Get Carter [1971]), Mike Hodges came up with this strong adaptation of a Jack Higgins novel about an IRA killer who flees to London when his conscience gets the better of him. Although there are pulpy elements – a former SAS man turned priest (Bob Hoskins) and his blind niece (Sammi Davis); a brutal East End gangster (Alan Bates); and a pair of IRA assassins sent to track him down – the film is held together by one of Mickey Rourke’s finest performances as a man sick of killing who finds himself unwillingly dragged into a situation where violence becomes inevitable when those he’s come to care about are threatened.

10 Rillington Place (1971): Director Richard Fleischer returned to the true crime genre several times during his career, but this is by far the best of those films, and arguably the best film he ever made. The grim and tawdry story of serial killer John Reginald Christie who murdered a number of women during and after the Second World War, hiding the bodies in and around his nondescript house in London, the film focuses on the murder of Beryl Evans, a tenant in the house with her simple husband Timothy. Before Christie himself was exposed as a murderer, Timothy Evans was tried, convicted and executed for the murder of Beryl, one of a number of cases which eventually led to the abolition of capital punishment in Britain. Fleischer captures the bleak, colourless atmosphere of post-war London and the cramped, hopeless lives of people struggling to get by, while Richard Attenborough is utterly chilling as the emotionally and sexually twisted pretender to middle class respectability.

Other Twilight Time disks of note: The Boston Strangler (Richard Fleischer, 1968); The Detective (Gordon Douglas, 1968); Tony Rome (1967) & Lady in Cement (1968), both also directed by Gordon Douglas; Hush … Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964) & Emperor of the North (1973), both directed by Robert Aldrich; Lilies of the Field (Ralph Nelson, 1963); Mysterious Island (Cy Endfield, 1961); Scorpio (Michael Winner, 1973).

New acquisitions not yet viewed: The Chase (Arthur Penn, 1966); Cutter’s Way (Ivan Passer, 1981); Eureka (Nicolas Roeg, 1983); Moby Dick (John Huston, 1956); Pretty Poison (Noel Black, 1968).

Network

Network has been churning out massive numbers of disks covering huge swaths of British film history for some years now, including so many comedies, mysteries and musicals that there would be no way to keep up with them all. This year, however, I bought three titles I’ve been looking for for ages (all three were actually released in late 2015).

80,000 Suspects (1963): This medical thriller came towards the end of director Val Guest’s string of great movies which began with The Quatermass Xperiment in 1955. Guest brought a fine sense of realism to his science fiction, horror, war and crime films, with excellent location work, strong performances and an eye for gritty social detail. 80,000 Suspects deals with a smallpox outbreak in England and the massive mobilization of civil authorities trying to contain it while tracking down every last contact. This aspect of the film is handled with Guest’s usual documentary strengths, but the film is weakened by the script’s over-emphasis on the troubled marriage of the lead doctor (Richard Johnson) and his wife (Claire Bloom). This shifts focus from the most dramatic aspects of the story to a somewhat cliched soap opera subplot. (Johnson and Bloom were immediately reunited for Robert Wise’s The Haunting that same year.) But despite this miscalculation, the film’s depiction of a modern city under siege is effectively chilling.

Robbery (1967): After a couple of modest features and some television work, Peter Yates essentially launched his long career with this tense, expertly constructed account of the Great Train Robbery. Co-produced by and starring Stanley Baker, it combines meticulous planning of the caper with some riveting action sequences which were quite unusual for a British film at the time. The opening car chase through the streets of London was so impressive that Steve McQueen sought Yates to direct Bullitt the next year, which in turn provided the basis for a successful, if uneven, career which lasted another three-and-a-half decades. Robbery belongs among the crime movie greats, but it took almost fifty years for it to become available in a high quality edition; Network did an excellent job on the transfer and the substantial extras.

West 11 (1963): After six years in which he made a handful of short documentaries and seven B movies – mystery, comedy, musical and exploitation – Michael Winner seemed to make his first serious film out of nowhere. Adapted by Keith Waterhouse and Willis Hall from Laura Del-Rivo’s novel The Furnished Room, this is a bleak story set in Notting Hill before it became trendy. With characters just emerging from the privations of the post-war period, living in cold-water walk-ups, hanging out in pubs and cafes where working people mingled with would-be artists and writers, it centres on Joe Beckett (Alfred Lynch), an aimless young man who can’t seem to live for the effort of trying to figure out why he’s alive. The location photography by Otto Heller captures a long-gone city in finely observed detail and Winner here reveals the considerable talent he had for assembling a great cast. This was the first of five distinctively English films Winner made in the mid-’60s before taking his chances in the United States. Given his highly conflicted reputation following that move, this brief period deserves some serious re-evaluation.

Shout! Factory

Shout! Factory have stepped up their efforts to produce definitive editions of genre movies which span the entire spectrum from big studio productions to low budget exploitation. This year I’ve enjoyed William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist III (1990), which includes both the theatrical version and a reconstructed director’s cut; despite the creative failures of William Friedkin’s supernatural misfire The Guardian (1990), the disk is worth a look for the interviews included; there’s an excellent, extras-packed edition of Dan O’Bannon’s Return of the Living Dead (1985), which still stands as one of the high points of horror comedy; an equally extras-packed edition of John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982), not simply his best work, but the best monster movie ever made; and, although I came to it late (it was released in 2012), Bertrand Tavernier’s sombre science fiction film, Death Watch (1980).

Kino Lorber

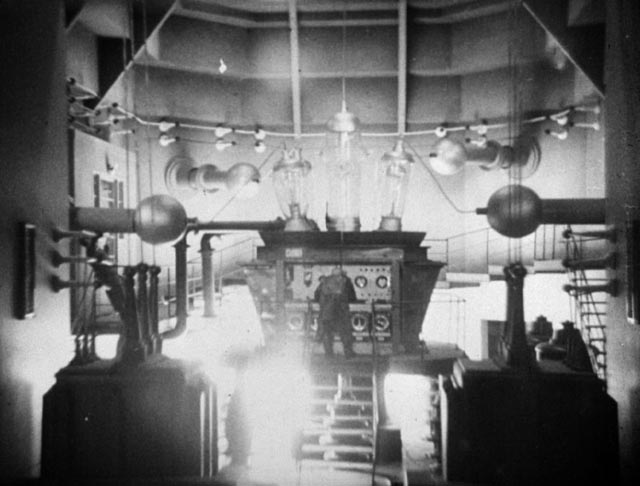

Although Kino Lorber have been churning out disks for the past couple of years, including a lot of older B movies, they tend to be a bit pricey. I only picked up two this year: Karl Hartl’s Gold (1934), an ambitious attempt to mount an epic Lang-like science fiction thriller in the early years of the Nazi regime; and John Sturges’ The Satan Bug (1965), which remains a rather dull and mostly thrill-less germ warfare thriller, but definitely looks its best in a new transfer.

Olive Films

Like Kino Lorber, Olive Films’ disks are rather expensive and usually extras-free (though they recently started an even more expensive deluxe line featuring supplements). Despite the price, I had to buy a copy of Cy Endfield’s Try and Get Me! (1950), a relentlessly bleak noir about an ordinary man driven by desperation to hook up with a petty criminal. Things go from bad to worse, climaxing in a grim act of communal violence. Endfield was blacklisted soon after this and went into exile in England.

Eureka/Masters of Cinema

Masters of Cinema from Eureka released a pair of highly desirable disks this year: King Hu’s Dragon Inn (1967) and A Touch of Zen (1971), films which redefined the venerable wuxia genre and set the standard for Chinese martial arts movies for the next few decades, although few that followed managed to achieve Hu’s sense of grandeur and narrative richness.

On my recent trip to England, I picked up a few older MoC disks, three upgrades from previous decent DVD editions – Peter Watkins’ Punishment Park (1971) and Raymond Bernard’s Wooden Crosses (1932) and Les Miserables (1934) – plus Andrew Bujalski’s retro comedy Computer Chess (2013).

Soda Pictures

I picked up two disks from British company Soda Pictures this year, the first a gorgeous (and long overdue) quality video release of Philip Ridley’s The Reflecting Skin (1990), a haunting horror-inflected fairy tale of childhood trauma, the second Ben Wheatley’s impressive if not entirely successful adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s novel High-Rise (2015).

Etiquette Pictures

Etiquette Pictures is a genuine boutique label, releasing only a few titles which the company is saving from almost complete obscurity. While both were released in 2015, I only saw James B. Harris’ Some Call it Loving and Patrick McGoohan’s Catch My Soul (both 1973) this year. Neither was a commercial success on release, which is not surprising as they defy audience expectations to follow their own idiosyncratic paths. Some Call it Loving is a perverse fairy tale, a variation on Sleeping Beauty, which is both lushly romantic and disturbing in its objectification of a woman as a blank object onto which the protagonist can project his own sexual desire. Catch My Soul is like the dark twin of Jesus Christ Superstar, a counter-cultural musical interpretation of Othello with a preacher (played by Richie Havens) undone by his own arrogance and jealousy.

Drafthouse

Yet another boutique label which lavishes great care on its releases, which include foreign, independent, documentary movies which range from the sublime to the ridiculous (have you seen Michael J. Paradise’s The Visitor?). This year they released a superlative Blu-ray edition of Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Look of Silence (2014), a companion film to 2012’s The Act of Killing, which manages to deepen and enrich the terrible history of the U.S.-backed Indonesian genocide of the ’60s. Is it tasteless to mention in the same breath their release of Why Don’t You Play in Hell? (2013), one of Sono Sion’s most outrageous entertainments, in which a group of teenage would-be filmmakers become involved in a yakuza war? It’s funny, bloody and excessive, and manages to explore the blurred line between movies and reality in interesting ways.

Synapse

And finally there’s Curt McDowell’s old-dark-house porn epic, Thundercrack! (1973), a strange, obsessive, polymorphously perverse tale of strangers stranded on a stormy night in a remote house where they get on each other’s nerves, and pair off in various ways (gay, straight, bestial) before they manage to escape. The disk is packed with interesting extras, including a full-length documentary about the underground filmmaking Kuchar brothers because George was heavily involved in the production. (This inspired me to get hold of Rufus Butler Seder’s Screamplay [1985], which also features George Kuchar and has a similar visually rich handmade aesthetic.)

Comments