Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963)

I haven’t been out to a movie in months, but I recently felt compelled to make the effort for a Sunday matinee screening of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963). This was part of Cineplex’s on-going series of classics revived for digital big screen showings – I’d previously seen and been generally impressed by the quality of Psycho, It’s a Wonderful Life, Sunset Boulevard and The Maltese Falcon. Luckily the theatre was almost empty – no more than 20 people – and those few were quite attentive, although one young couple did snicker a few times. Unfortunately the picture quality in this instance was so poor it looked as if they were screening it from a DVD. The image was really soft, with very little detail in wide shots (closer shots were somewhat better), colours were muted and dull, and the whole thing looked as if it had been timed as day-for-night; even shots in bright sunshine looked as if they were taking place at dusk.

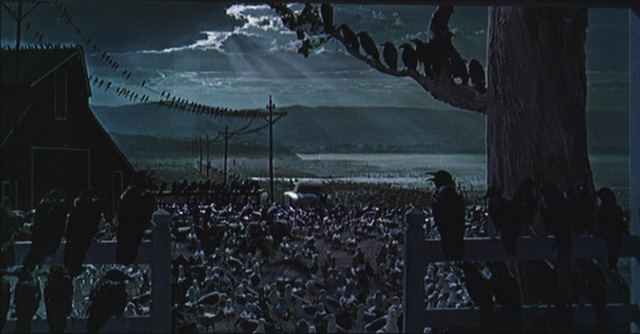

But despite the crap presentation, it was great to see it again on a big screen (I’d previously had the opportunity in the early ’80s when several of Hitchcock’s movies were restored and given a theatrical re-release). And I was confirmed in my opinion that The Birds is one of Hitchcock’s greatest films, virtually flawless in construction, working so well dramatically that any weaknesses in the optical effects (at least viewed from today’s slick CG standard) seem irrelevant. Those shots – composites of location footage, matte paintings, layers of superimposition – have great dramatic power; one of them is one of my all-time favourite shots from any movie I’ve ever seen: after the big attack on the town, with the explosion of the gas station, a chaotic and noisy depiction of terror and violence, Hitchcock cuts to a “god’s eye” view of the town, all sound dropped except for the wind. After holding on this for a long moment, a single gull glides in from the side of the frame, then another, and another … the town so small below appears fragile and vulnerable against the implacably calm gathering of the birds high above.

Perhaps the biggest thing I noticed this time was that the performances seem to improve with the increase in scale – something I was really struck by when I saw a screening of Psycho six years ago. Hitchcock’s reputation with regard to actors has always been problematic (I have a friend, a high school drama teacher, who thinks he was a terrible director of actors), but here once again it was possible to see nuances and subtleties which are not always apparent on a TV screen. Even Tippi Hedren, despite her limited range, gives an affecting performance, with minor supporting actors providing colour and shading to Evan Hunter’s superb script. Just look at the short scene in which Melanie stops in at the Bodega Bay store-cum-post office to ask directions to the Brenner place and the lightly amused way in which she has to pry the information, bit by bit, from the friendly but very laconic storekeeper (John McGovern); it’s a tiny gem of character detail and comic timing, and a key indicator of why the film works so well.

Although The Birds is a disaster film, the granddaddy of all Nature-turns-on-Mankind stories, Hunter and Hitchcock ease us into it with skillful misdirection. It begins as a finely tuned romantic comedy about Melanie (Hedren), a spoilt heiress, and Mitch Brenner (Rod Taylor), a lawyer from the small town of Bodega Bay who now practices in San Francisco. They meet cute in a pet shop when he recognizes her and plays a humiliating trick on her by pretending to think she’s a store clerk, exposing her complete ignorance of the birds on display. His rather low opinion of her is based on society page stories of her privileged escapades. Her response is a mixture of anger and attraction, and she follows him back to Bodega Bay for the weekend, hoping to make him feel guilty for his trick with an act of (self-serving) generosity.

But in the middle of meet-cute part two, she is abruptly, inexplicably injured by a seagull which attacks her; the comic tone shifts, her injury displacing the amusing antagonism as it hints at something darker which goes beyond them and their minor emotional game. From there, the film quietly slips into an equally effective psycho-drama which revolves around the complicated relationships within Mitch’s family: he is bound by his fearful, widowed mother Lydia’s need for support, a need which has already damaged at least one relationship – with Annie (Suzanne Pleshette), the town’s schoolteacher, who followed Mitch to Bodega Bay and stayed to be near him although Lydia (Jessica Tandy) managed to shut her out. Lydia reacts to Melanie with distrust and disdain based on those same embarrassing newspaper reports of her behaviour (which Melanie explains away as smears perpetrated by a newspaper rival of her father’s).

Persuaded to stay in town for the weekend, Melanie rents a room from Annie and here again Hitchcock draws some wonderfully subtle business from his actors, particularly in the way he shoots and edits the scene in which Annie can’t help overhearing Melanie making arrangements with Mitch over the phone. This scene is a textbook example of how to play multiple levels in a single scene, allowing both characters’ feelings to operate clearly and sympathetically beneath the surface.

As with the second meet-cute sequence, this quietly tense scene is ruptured by another moment of ominous bird behaviour, with a gull crashing into the front door and dying on the porch. From here, things escalate as Melanie navigates the issues which complicate a possible relationship with Mitch while the birds grow more dangerously aggressive. There’s the death of a neighbouring farmer – discovered by Lydia in one of Hitchcock’s signature moments of carefully constructed suspense; an attack on the kids’ birthday party in the Brenner backyard; the subsequent attack on the school; then a larger more destructive attack on the town, in which we see multiple deaths, and which is followed by the frightened locals’ attempts to deal with their incomprehension by finding someone to blame, specifically Melanie, who is deemed to be the source of the inexplicable attacks, and is hysterically accused of being evil.

With the defensive retreat into the Brenner home, which Mitch does his best to seal up against further attack, the tensions within the family rise to the surface. Lydia accuses Mitch of being inadequate to keep them all safe (unlike his now-deceased father), while Mitch’s younger sister Cathy (Veronica Cartright), now all but ignored by her increasingly hysterical mother, clings to Melanie for safety. Perhaps the most unsettling aspect of the film is Hitchcock’s refusal to offer a clear resolution; order is not restored; the birds are not defeated, nor is any plausible explanation for their attacks offered. After two further assaults on the house, during which Melanie is finally traumatized into an almost catatonic state, all the survivors can do is slip out of the house during a calm interlude and drive away with no idea where safety might lie. The semblance of balance within the family has only been obtained through the infantilization of Melanie, rendering her helpless and thus no longer a threat to Lydia, but rather a dependent needing the mother’s comfort.

In a standard romantic comedy, the focus would remain on Melanie and Mitch and their mutual misunderstandings, which the plot’s complications would eventually resolve. Melanie begins as the seemingly flighty heiress, but is eventually revealed to have a deeper, more sturdy character – learning something which will take her beyond the good works she does as a volunteer on various days of the week, which are still a mark of her privilege. Or in a more regressive variant, giving up all the trappings of that privilege in order to subordinate herself to the man who wins her. Meanwhile, Mitch begins as a bit of a self-righteous moralist, dedicated to social causes and contemptuous of her privilege – until he learns something of what lies beneath the surface and discovers that she’s also a worthy person, perhaps even joining him in his righteous legal causes.

But all this goes off the rails with the first bird attack on Melanie; Mitch’s concern defuses his sense of moral superiority and he suddenly responds to her simply as a person in distress. There is no need for games and role playing; they can deal with each other with emotional directness. But the social environment he brings her into is almost as hostile as the natural environment which caused her injury. Mitch is struggling to assert himself against a dominant mother (shades of Norman and Mrs. Bates) who clings to him while barely concealing a sense of disappointment that he has been unable to fully replace her lost husband. Mitch is called on to be protective and supportive of the two women (not to forget his younger sister) in different, mutually exclusive ways. It is only as the bird attacks continue, cracking Lydia’s hard defensive shell, that Mitch is able to fully assume his role as dominant male – and yet there’s the troubling fact that this role is essentially replacing the lost father, becoming worthy of his mother while reducing Melanie to the position of a second dependent child.

As Nature remains disordered, the new order established within the family is emotionally and psychologically unhealthy.

The film has progressed from light rom-com to apocalyptic nightmare, the easy and familiar platitudes of movie relationships completely undermined, family and romantic bonds exposed as pathological and inadequate barriers against a hostile universe. The final shot of the birds gathered in the Brenner yard, waiting for whatever reason before attacking again for whatever reason, gives us what may be the bleakest of all conclusions in Hitchcock’s work.

Comments