Compulsive Viewing: A Personal Pathology Part 1

I usually only have time to write once a week for this blog, and my occasional obligations to Blogcritics (i.e. the free review copies I get through them) have pushed me into the habit of doing reviews more often than more general posts about broader topics (which was what I actually anticipated when I started this thing two-and-a-half years ago). In addition, the emphasis here gets skewed to some degree by the almost random nature of what I get assigned by Blogcritics, perhaps giving a false impression about my interests (I miss a lot of the disks I’d really like to get hold of because they have a first-come first-served system for assignments, and even I can’t keep compulsively checking to see what’s being offered).

The point is: I end up not writing about the majority of the movies I watch (and I do watch a lot!), so this blog isn’t exactly representative of my tastes and habits.

So here, for what it’s worth, is a quick survey of one month’s viewing (late April to the end of May). Why these movies? I have to put it down to a compulsion – my viewing is something of a pathological habit, ranging in numerous directions in some futile attempt to experience as much of contemporary film and film history as my limited time can squeeze in.

What I’ve written about already from this month are Jancso’s My Way Home and The Round-Up; Kobayashi’s The Thick-Walled Room, I Will Buy You, Black River and The Inheritance; Dearden’s The Bells Go Down and Jennings’ Fires Were Started; the Boulting Brothers’ Seven Days to Noon and Seth Holt’s Nowhere To Go; John Krish’s Captured and H.M.P.; B.S. Johnson’s You’re Human Like the Rest of Them; Andy Muschietti’s Mama. Looking at my records (yes, I do keep records), I see some thirty-odd additional titles for the month. If that doesn’t indicate something pathological, I’m not sure what would!

So here, in roughly chronological order of viewing, is my brain’s recent diet of movies:

Bait (Kimble Rendall, 2012)

One of those great, cheesy B-movie ideas – after a tsunami, a group of Australians get trapped in a flooded supermarket with a hungry great white shark – which more or less delivers exactly what you want from such a concept; human conflict and shark feeding frenzies, though I have to agree with my friend Curtis that it’s suspicious that the two Asian characters are the first victims – perhaps here “Asian” is code for Red Shirt. (A friend lent me a DVD copy.)

The Dust Bowl (Ken Burns, 2012)

A fascinating documentary about what happened in a central area of the States throughout the ’30s, an environmental catastrophe which in popular memory has become almost synonymous with the Depression; inappropriate farming techniques which destroyed the native grasslands resulted in endless massive dust storms which not only swept away millions of tons of topsoil, but actually killed people by clogging their lungs. Without ever overstating the present-day parallels, Burns and writer Dayton Duncan raise pertinent questions about human impact on the environment and the role of government in alleviating the effects of natural and economic disasters. But what really impresses is the amazing archival material documenting the terrifying storms. (As usual with Burns’ disks, the Blu-ray includes numerous supplements fleshing out some of the film’s themes and stories.)

Cosmopolis (David Cronenberg, 2012)

I’m sorry I missed this in the theatre because it seems like a return to form for Cronenberg after years of coasting. In fact, it’s his best film since Crash (1996), another adaptation of a “difficult” novel. And who knew that Robert (“Edward Cullen”) Pattinson had this in him? Don DeLillo’s story is a metaphor for the economic chaos wrought by the 1%, played out as an insanely wealthy money manager’s cross-city drive in search of a haircut as society collapses around him. Much of the film takes place in the back of a stretch limo, with the collapsing world glimpsed through the windows as Eric Packer is consumed by meaningless trivialities. (The same friend lent me a DVD copy.)

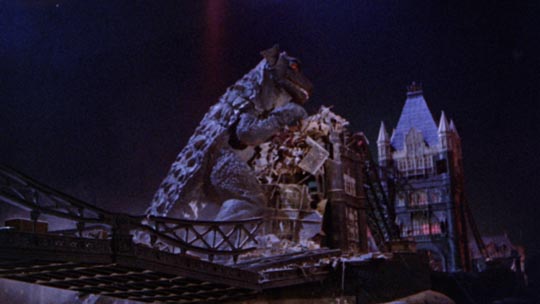

Gorgo (Eugène Lourié, 1961)

Eugène Lourié’s third and final giant monster movie is cliched from beginning to end, but the setting (rural Ireland and London) makes for novelty, and Freddie Young’s Technicolor cinematography offers some eye-popping visuals. Apparently the producers ran out of money part way through and editor Eric Boyd-Perkins had to do a major salvage job to create a coherent narrative – not that that really mattered to fans of the genre, who certainly got their money’s worth in terms of destructive mayhem. (The Blu-ray includes an interesting making-of featurette, plus a lot of text and image supplements, including a French comic book adaptation.)

River of No Return (Otto Preminger, 1954)

The western seems like an unsuitable genre for the cosmopolitan Preminger, and Marilyn Monroe seems like the wrong kind of actress, but despite the conventional script (an estranged father, his young son and a frontier showgirl head down a dangerous river on a raft, pursued by hostile Indians, and in pursuit of the scoundrel who betrayed them) and the discordant casting, Preminger obviously enjoyed the vistas provided by the western mountain ranges and the movie is consistently impressive to look at. (No extras on the Fox Blu-ray.)

Zero Dark Thirty (Kathryn Bigelow, 2012)

Bigelow’s studied neutrality about what’s been going on in “the war on terror” for more than a decade raises questions which the film doesn’t attempt to answer. As the radically divergent responses to the movie indicate, it serves as a Rorschach test for audiences. I have to admit that, for me, it lacks the impact of The Hurt Locker because we never get close to Maya, the CIA analyst played by Jessica Chastain. It’s a procedural which deliberately avoids passing judgement on the procedures used – including the early scenes of torture … but by the time the Seals kill Bin Laden, there’s a peculiar sense of anticlimax as if the characters (and we in the audience) have already forgotten why he was being hunted in the first place. (The Blu-ray’s supplements focus on the technical challenges of making the film, not on its historical and moral implications.)

French Cancan (Jean Renoir, 1954)

Renoir’s colourful ode to show biz has entrepreneur Henri Danglard (Jean Gabin) doing whatever he can to build and open the Moulin Rouge and restore the famous (disreputable) dance to its rightful place in French culture. All the show biz cliches are here, along with a refreshingly non-judgmental attitude towards sexuality which sets it apart from American films of the period. Renoir stages it all with terrific energy and charm. (The BFI Region B Blu-ray includes a one-hour retrospective documentary about the making of the film and Renoir’s problematic return to French filmmaking after his exile in Hollywood during and after the Second World War.)

Sanctum (Alister Grierson, 2011)

This James Cameron-produced adventure is like Bruce Hunt’s The Cave and Neil Marshall’s The Descent – just without the monsters. A group of cave divers get trapped in the world’s largest unexplored underwater cave where they discover that, well, man is man’s own worst enemy. Cliched characters and relationships provide predictable “drama”, leaving the viewer wishing that they’d run into some kind of flesh-eating monsters … (Someone gave me the Blu-ray; I watched the 2D version and skimmed the extras which include some deleted scenes and behind-the-scenes featurettes revealing a lot of bluescreen work; I didn’t listen to the commentary with the director, producer, and lead actor.)

Kwaidan (Masaki Kobayashi, 1964)

I re-watched this (the longer restored version released a while back by Masters of Cinema) for some context when I was reviewing the Eclipse Kobayashi box set, and once again appreciated the rich, colourful design while remaining somewhat detached from the ghost stories themselves. While aesthetically pleasing, the studio-bound stylized visuals create a distance which prevents any real emotional engagement with the characters. (Region 2 DVD with no extras other than a fat booklet containing the original Lafcadio Hearn stories and an interview with Kobayashi.)

Rider on the Rain (Rene Clement, 1970)

I can recall seeing trailers for this thriller back when it first came out, but for some reason never actually saw the film. Sebastien Japrisot’s script is clever without being particularly convincing, but the central performance of Marlene Jobert as a woman who, after being raped in her own home, kills her attacker and dumps his body over a cliff is so full of nuance that the film almost becomes a proto-feminist argument against the treatment of women in popular culture. She keeps the rape secret because she has an oppressively controlling husband, but a stranger shows up who seems to know what happened and she becomes involved in a cat-and-mouse game with the man (played by Charles Bronson). Clement shot the film simultaneously in two versions, French and English. In the first, of course, Bronson is dubbed; in the second, all the European actors speak heavily accented English. Despite the loss of Bronson’s voice, the French version is definitely the better of the two. (Region 2 DVD containing both the French and the slightly shorter English versions of the film.)

V/H/S (various directors, 2012)

Although the found-footage genre has been stretched to the breaking point in the past few years, this anthology offers some genuinely creepy atmosphere and a few authentic scares – if you can get past the first ten minutes or so where the deliberately bad camerawork and excessive use of tape dropouts is virtually unwatchable. As with any anthology, the individual stories are somewhat uneven, and most of them kind of peter out at the end, but for a horror fan there’s enough uneasiness here to satisfy. (The Blu-ray includes a collection of brief extras including interviews, behind-the-scenes clips and a commentary which I haven’t listened to.)

Grand Hotel (Edmund Goulding, 1932)

This grandaddy of ensemble dramas (from Vicki Baum’s novel) is creaky as hell, but nonetheless thoroughly engaging as we follow a varied collection of people through a couple of days at a big hotel in Berlin. There’s tragic romance (Garbo’s famous “I vant to be alone” moment), class conflict (combined with some broad comedy involving Lionel Barrymore’s terminally ill worker), excitable theatre folk, and an unscrupulous (if not outright criminal) industrialist. (The Warner Blu-ray contains the kind of extras which used to be standard on the studio’s DVD releases a few years back: a commentary, a short featurette on the production, a Vitaphone musical parody of the film, newsreel of the glitzy premiere and trailers for this and the 1945 remake, Weekend at the Waldorf.)

The Man Who Knew Too Much (Alfred Hitchcock, 1934)

I’ve always preferred Hitchcock’s first try at this story (the first of his truly Hitchcockian thrillers) to the American remake. The later version irritates me with its smug cultural complacency (just watch James Stewart trying to sit down in that funny Arab restaurant – hilarious!), while the original not only has the great Peter Lorre (in his first English-language role – if you don’t count the inferior English version of Fritz Lang’s M) as its main villain, but it climaxes with that terrific siege in a gloomy London street. This is a darker movie with a greater sense of threat. (The Criterion Blu-ray includes an appreciation by Hitchcock fan Guillermo del Toro, two half-hour interviews with Hitchcock from 1972 by Ingrid Bergman’s daughter Pia Lindstrom and historian William K. Everson, and excerpts from Truffaut’s extensive 1962 interviews with the director.)

Rosemary’s Baby (Roman Polanski, 1968)

Polanski’s first American film is a masterpiece of narrative precision, packed with a terrific cast who effortlessly find the right balance between quotidian comedy and subtle menace. Still the best evocation of “neighbours from Hell” (in this case, literally!). Apparently Polanski and John Cassavetes didn’t get along, but Cassavetes’ arrogantly opportunistic Guy is one of the most chilling depictions of what the feminist revolution of the ’60s was aimed at: he has no compunctions about drugging and prostituting his wife to Satan to get ahead in his career. (The Criterion Blu-ray includes an interesting lengthy retrospective documentary about the making of the film, a 1997 interview with author Ira Levin about the book and its sequel, and a feature-length documentary about the life of composer Krzysztof Komeda, who wrote the score – which I haven’t watched yet.)

Broken City (Allen Hughes, 2013)

The Hughes Brothers never really fulfilled the promise shown in Menace II Society (1993), their grimly powerful story of violent ghetto life. Now, after twenty years of TV work and slick and empty features like From Hell (2001) and The Book of Eli (2010), here’s Allen labouring through a tired, completely unoriginal story of big city corruption which wastes an excellent cast in a series of all-too-obvious complications. (The Blue-ray includes a handful of deleted scenes and a making-of featurette in which everyone involved works overtime to convince us that this is a really complex and sophisticated piece of work.)

Innocent Bystanders (Peter Collinson, 1972)

After a decade of James Bond, cynicism had become the default attitude in the anti-Bond spy movies (the Harry Palmer series with Michael Caine, Anthony Mann’s A Dandy In Aspic, Martin Ritt’s The Spy Who Came In From the Cold, John Huston’s The Kremlin Letter, and so on), but by the time of this effort by the director of the original Italian Job (1969), the absence of any possibility of an alternative drains that cynicism of all its dramatic power. Stanley Baker (with only four years of mostly TV work left before his early death) is a burnt-out agent given one last assignment: find and bring in a scientist who has gone into hiding after escaping from a Siberian prison camp. But John Craig’s unhappy boss Loomis (the always enjoyable Donald Pleasance) is using the case to get rid of the troublesome agent, setting a ruthless younger pair on his trail to dispose of him and take possession of the scientist when he’s found. A decent cast and attractive locations can’t raise the narrative above the routine. (The Olive Films Blu-ray has no extras.)

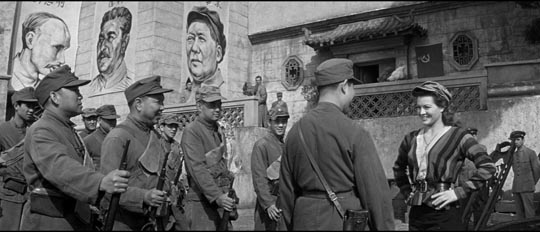

China Gate (Sam Fuller, 1957)

Another of Fuller’s treatments of men (and women) in war, finding degrees of individual integrity and heroism in morally dubious situations. Here, a group of legionnaires go deep into enemy territory to destroy a key supply line, led by a half Asian, half French woman (Angie Dickinson) who has been rejected by the American father of her son because the kid came out looking Chinese. Needless to say, the mission eventually heals the racist rift (after great sacrifice). The film’s hard-line anti-communism isn’t surprising, but what’s difficult to swallow is its un-nuanced assertion that the French had brought civilization to Southeast Asia (through the selfless work of priests and the Foreign Legion) and the damned commies were destroying that precious gift with their godless war. (As usual, there are no extras on the Olive Films Blu-ray.)

The Devil and Miss Jones (Sam Wood, 1941)

Having read a number of glowing reviews when this comedy was recently released on Blu-ray, I had high hopes of discovering a previously unknown gem. Well, it disappointed a little in the laugh-out-loud department, but is packed with charm and occasionally surprising criticism of American capitalism. Charles Coburn as Merrick, the world’s wealthiest man, goes undercover in a New York department store he owns to uncover the troublemakers who have been demonstrating against poor treatment of the employees. He’s taken under the helpful wing of Mary (the wonderful Jean Arthur), whose boyfriend Joe (Robert Cummings) is leader of the union organizers. The film actually gives Joe a podium from which to criticize capitalist exploitation of the workers, but by the end, not so surprisingly, Norman Krasna’s script offers an individualist solution: inequity isn’t so much inherent in the system as it is a result of easily corrected misunderstandings. Once Merrick has been introduced to his employees, he realizes they should be treated with more respect and everyone can live happily ever after. (Olive Films Blu-ray, no extras again.)

To be continued …

Comments