Unearthed Treasure: Greg Hanec’s Downtime (1985)

Last Thursday I had the rare opportunity to see one of the best films ever made in Winnipeg. It almost didn’t happen. Since I started a new day job a few weeks ago which requires me to get up at 5:30 every morning, I’m reluctant to drag myself out on weekday evenings. On top of which the weather was wretched – howling wind and freezing cold rain. But if that wasn’t bad enough, my lack of local pop culture awareness meant that it had completely escaped my attention that that was the evening of the Justin Bieber concert at the downtown MTS Centre.

I’d given myself plenty of time to get to the Cinematheque because I expected to meet a couple of friends at the theatre before the show; but what should have been a quick ten-minute bus ride turned into an almost intolerable ordeal. Creeping along by inches in a Bieber-caused traffic jam, the bus took half an hour to get to the halfway point at the University of Winnipeg. It was beginning to look as if I wouldn’t make it in time for the start of the film. I pushed my way out of the crowded bus at the U of W and started to run in the wind and rain, eventually reaching the theatre a few minutes before show time, exhausted, gasping for breath and soaked to the skin.

But in retrospect, that “ordeal” seems somehow appropriate because Greg Hanec’s Downtime is about the crushing weight of existence on four young urban dwellers for whom inertia has obliterated any sense of purpose. No matter what they try to do, they never get anywhere.

Downtime (1985)

Downtime was made in the mid-’80s, the first feature produced by a member of the Winnipeg Film Group. It was made for a paltry $16,000 against the disbelief and even derision of Hanec’s fellow WFG members, who believed that you had to work your way up arduously through various stages from short films to gradually longer ones before you’d earned the right to make a feature. Hanec and co-creator Mitch Brown (who wrote the script and co-edited) saw no reason to wait and the result was a stark, surprisingly funny urban nightmare which was invited to the 1986 Berlin Film Festival (the first film from Manitoba ever screened there).

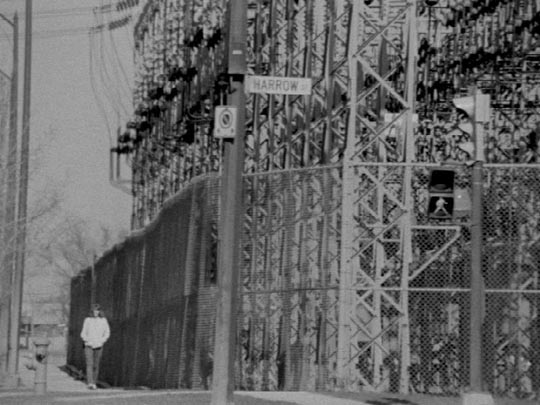

The impetus for Thursday’s event was the long-overdue launch of the film on DVD, but Greg chose to screen one of the only two remaining 16mm prints. As bumpy and scratched as the print was, it was the right choice because the visual texture of the 16mm black and white is a crucial part of the film’s identity. (The DVD, transferred from the original negative, itself a bit battered, looks almost too sharp and “clean”; and the brightness appears to have been boosted a bit, so the shadows aren’t quite as deep as on the print.) And despite the modesty of scale, the film also benefits greatly from being seen on an actual theatre screen where the emptiness of its spaces and the occasional looming close-ups take on a striking power. The other advantage of seeing it in a theatre with an (appreciative) audience is that the film’s distinctive rhythms, the swings from tension and tedium to humour and release, benefit from a communal response.

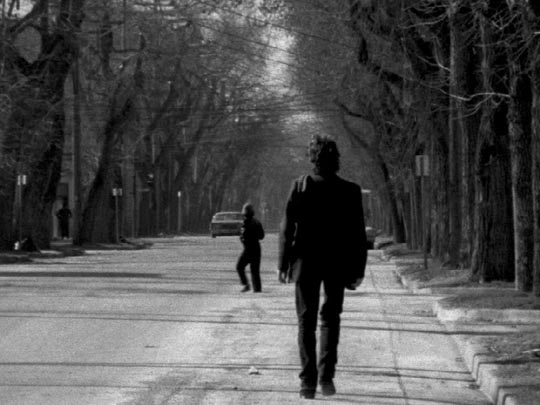

There’s a formal rigour to the film’s structure and visual strategies. Scenes begin and end in lengthy blacks, separated by urban tableau images which emphasize the global nature of the bleakness we experience within the scenes themselves. Those scenes are mostly played in long master shots, with only occasional internal editing. For this reason, Downtime has often been compared to Jim Jarmusch’s breakthrough Stranger Than Paradise, a film initially released as Greg and Mitch Brown were completing the editing. But despite a certain superficial resemblance, there are real differences between the two films and ultimately the attempt at comparison is unfair to Downtime.

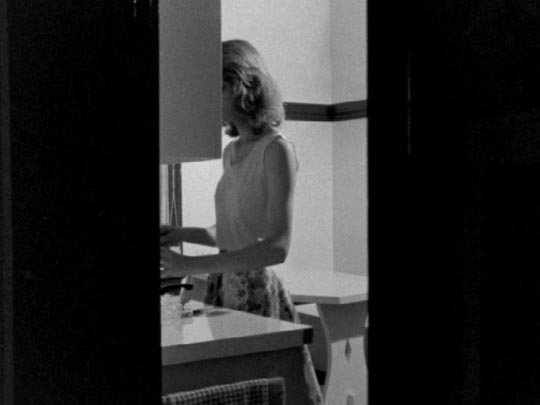

Jarmusch constructed Stranger Than Paradise as a series of masters with the camera perfectly placed to capture every detail of a scene, its focus on the rhythms and nuances of performance. His film is a masterful comedy of character. Greg’s locked off camera, in contrast, is deliberately limited in its field of view; characters pass in and out of frame, often with crucial elements of action occurring off-screen, indicated only by shadows in the background or sounds. Greg attributes this approach to the influence of Bergman (it’s a technique that Woody Allen used increasingly as the influence of Bergman took hold of his work in the late ’70s and ’80s). But Downtime has no pretensions to be a kind of Bergmanesque psychodrama. The technique is used here as a way to convey the implacable weight of the film’s physical environment and the wraith-like, almost ephemeral presence of characters who can barely make their existence felt.

We first meet the Woman (Maureen Gammelseter) behind the counter of a tiny corner store, passively waiting to be activated from an almost catatonic state by the entrance of a customer. The first customer, the Man (Padraic Obeirn), buys a litre of milk and at the end of the transaction, while barely seeming to acknowledge her presence, asks the Woman out. She says no and he just leaves. From then on, the film alternates between their lives – her in the store and her completely bare apartment; him doing his job as a school janitor and sitting aimlessly alone in his own apartment. They have three more encounters over the course of the film, each a clumsy attempt on his part to make some kind of contact, to raise some kind of response from her. But the inertia which grips her makes it impossible for her to react.

Set against these two are another woman, Debbie (Debbie Williamson), and a second man, Ray (Ray Impey). Debbie is a non-stop talker with no sense of personal space, who forces her way into the Woman’s life after they meet at a laundromat. She shows up unannounced (at one point walking into the Woman’s bedroom while she’s sleeping, vaguely claiming that “the door was open”), imposes on others and seems totally oblivious. She invites the Woman to a party, with Ray to drive them; this is one of the film’s highlights as they end up at a house where nothing is going on and an old man refuses to let them in.

Debbie works at a movie theatre (the late, lamented Cinema 3 on Ellice Avenue), where we glimpse a scene from what appears to be an excruciatingly tedious movie about aimlessness and inertia (yet another indication of Hanec’s self-aware humour). She moves in with Ray, but there’s obviously no connection between them; the bizarre scene in which she tells Ray that she’s flushed his toothbrush down the toilet forms part of a comic triptych about the meaninglessness of action which includes the “party” scene and the attempted robbery at the store. The formation of this “couple” is as much a dead end as the inability of the Man and the Woman to get together. And in the end, the Woman still stands behind the store’s counter, waiting …

With its stark, high contrast, shadow-filled black and white images (shot by Hanec himself), and the peculiar broken rhythms of the performances, Downtime reminds me a little of Eraserhead (though, as with Stranger Than Paradise, Greg hadn’t seen Lynch’s masterpiece before shooting his own film). Much of Downtime‘s comedy arises from the same kind of dysfunctional affect that marks the exchanges between Henry Spencer and others in Lynch’s film, where communication has become all but impossible because meaning can never emerge from the spaces between one character’s words and another’s response.

Hanec’s boldest formal strategy is the slow fade to black between scenes and those tableau shots which repeatedly interrupt the “narrative”. Here, he builds into the film’s fabric a sense of inertia, the virtual impossibility of moving forward, which holds the characters in their crushing stasis. Downtime is the work of a filmmaker who has thought carefully about the ways in which images, editing and sound create meanings which go beyond the thematics of drama, to express something far less tangible, but deeper than narrative. As in Lynch’s work, the essence of Hanec’s achievement here is a mood, an expression of existential dread which is nonetheless viewed as deeply comic, not in spite of but because of its hopelessness. I can only think of one other film which makes boredom and hopelessness as entertaining as this: Chris Smith’s brilliant exploration of soul-crushing dead-end labour in American Job (1996).

There are probably a number of reasons why this remarkable film virtually disappeared from view after its appearance in Berlin. One was that unfair comparison with Stranger Than Paradise; another is its awkward (from a commercial point of view) length. At only 65 minutes, it doesn’t fit accepted standards for a feature (following the screening, Greg mentioned that the first cut had been considerably longer: I’d love to see the deleted scenes!). A third reason is no doubt that it came from a young, unknown filmmaker working in the boondocks of Winnipeg – it would be several more years before Guy Maddin managed to break out of this invisible box with his far more quirky, but much shallower Tales From the Gimli Hospital (1989).

Perhaps now that it’s available on DVD, Downtime will get the wider recognition it deserves.

*

The evening was made doubly worthwhile by an engaging discussion after the screening, moderated by filmmaker John Kozak, in which Greg and lead actress Maureen Gammelseter offered amusing anecdotes about the filming and insights into their creative process.

As for the DVD itself, it’s nicely produced, with a sharp image and a fair representation of the 16mm print’s harsh soundtrack. Two of Hanec’s shorts are included – the very early Music, in which we get a glimpse of a startlingly young Greg Hanec, and the recent very brief piece he made for the Cinematheque’s 25th anniversary, Fast Slow Single. There’s also a 27-minute interview with the director, conducted by John Kozak in Hanec-cohort Barry Gibson’s used book store, in which he talks about the film’s origins and influences.

Comments