Otto Preminger and Anatomy of a Murder (1959)

Otto Preminger’s Anatomy of a Murder (1959) is the quintessential courtroom drama. Looked at now (in an excellent Blu-ray edition from Criterion) as a perfect expression of its genre, it may even seem formulaic in light of everything that’s been seen since its release. The crime, of course, is murder. Who did it is not in doubt: Lieutenant Manion (Ben Gazzara) shot bartender Barney Quill in front of a roomful of customers. The trial hinges on the question of motive and justification: did Quill rape Manion’s wife Laura (Lee Remick), and did that cause a burst of temporary insanity, an uncontrollable rage?

Then there’s the defence team: country lawyer Paul Biegler (James Stewart), who’d rather be out fishing every day than in a courtroom, and his sidekick Parnell McCarthy (Arthur O’Connell), an alcoholic who loves the law and its workings even more than the bottle – so he agrees to give up drinking for the duration when Biegler decides to take the case.

Opposite them are the prosecutors, the out-of-his-depth District Attorney Mitch Lodwick (Brooks West) and Assistant State Attorney General Claude Dancer (George C. Scott), brought into Michigan’s Upper Peninsular to oversee the small-town trial.

The dynamics of Preminger’s film might have been borrowed from the long-running Perry Mason series (1957-66) which started its run two years before the feature was made, but the movie was actually based on a 1958 novel written by John Donaldson Voelker (writing as Robert Traver). Voelker was a lawyer and judge, born in the small town of Ishpeming, where the film was shot entirely on location, and in 1952 he defended a soldier named Coleman Peterson who was accused of murdering Maurice Chenoweth after Chenoweth supposedly raped Peterson’s wife. Voelker, like Biegler, got his client off with a verdict of temporary insanity.

Despite the fact that the novel and film follow this real case closely, and that the original defence attorney wrote the book, Anatomy of a Murder departs from the expected formula and becomes something unique in the genre. Perry Mason ran for years on the absolute moral certainty of its protagonist, week after week humiliating the prosecution by uncovering a truth which the state was too lazy or short-sighted to discover. Even the critical favourite The Verdict (Sidney Lumet, 1982) was rooted in this sense of absolute moral certainty, with the alcoholic underdog lawyer played by Paul Newman triumphantly sticking it to the powerful forces opposing him.

But in Anatomy of a Murder, there is no sense of certainty. Preminger, trained in the law himself in Vienna before he emigrated to the States and a successful movie career, was drawn to the central idea of the novel that the law is essentially a form of theatre. What makes Anatomy of a Murder stand out from its genre is the idea that the trial is not finally about getting to the truth, but rather about dueling performances, with the best actor taking home the prize.

Biegler takes the case not because he’s convinced of Banion’s innocence, but because he sees a way of playing the game with a chance of success, or rather that there’s a legal way to get the man off regardless of his guilt. It was a stroke of genius on Preminger’s part to cast James Stewart in the role, an actor with a big store of aw-shucks honesty behind him, and Stewart rises to the occasion by giving probably the best performance of his career. He plays a version of his screen persona in the courtroom, the simple, indignant country lawyer struggling to keep up with the powerful attorney sent down from the capital; but we can see at every moment that this is a performance, a finely tuned manipulation of the courtroom stage by a very smart and wily actor up against an opponent whose mistake it is to believe that the law is actually a matter of clarifying the facts of the case for the jury.

As the trial progresses, the audience is forced to make judgements just like the jury in the film, although we viewers are privy to additional information because we spend so much time outside the courtroom with Biegler, McCarthy, Manion and Laura. Which is why, as we see Biegler successfully manoeuvre the case towards an acquittal, we find our own doubts growing increasingly stronger. By the time Biegler triumphantly crushes Dancer with a final surprise witness and piece of evidence (the climax of virtually every episode of Perry Mason, in which Perry’s client is conclusively proven innocent and the real culprit suddenly offers a hysterical confession), we are pretty certain that Laura willingly had sex with Barney Quill, that Laura’s injuries were inflicted by Manion himself when he found out and beat her, and that he killed the bartender in deliberate cold blood. But within the confines of the courtroom and the rules of the law, that “truth” has been supplanted by the defence story of the rape and an uncontrollable act of revenge because Biegler is the more skillful performer.

Preminger was fond of looking closely at vast and powerful institutions and dissecting the ways in which they function and establish their own reality. It may be because of his own background in the law that Anatomy of a Murder emerges as his finest, most perfectly accomplished movie, one which remains virtually unique in its willingness to question and leave finally unresolved the issue of how much the law is actually involved with establishing truth. The seemingly endless reports of wrongful convictions that turn up regularly in the press appear to prove the film’s thesis that verdicts ultimately depend on the performances of the opposing lawyers rather than any objective truth.

As in the earlier The Moon Is Blue (1953), Preminger used Anatomy of a Murder to push against the restrictive Production Code. There were obvious objections to the frank talk of rape and the production of Laura Manion’s ripped panties in the courtroom, but Preminger refused to back down. He was one of the prime movers in the final collapse of the Code a few years later, insisting on making a film for adults, people mature enough to take a dose a realism.

Although it seems counter-intuitive, Preminger commissioned Duke Ellington (who appears in the film briefly, jamming with Stewart’s character in a roadhouse) to write one of the first genuine jazz scores for a Hollywood movie. Jazz, with its urban associations, should seem out of place in this rural setting, but it actually complements the film’s themes very well; after all, what Biegler does in court is a kind of improvisatory performance, riffing on themes, responding spontaneously to the playing of the opposing attorney in a kind of jazz theatre.

The entire cast is superb, with Gazzara and Remick conveying the toxic essence of their marriage largely through unspoken gestures and looks; O’Connell exposes the emotional core of an attachment to the law which complements Stewart’s intellectual investment in the game; in a stroke of publicity genius, Preminger cast attorney Joseph N. Welch as the judge – Welch was the man who finally put an end to Joseph McCarthy’s witch-hunting in Congress with his quietly indignant “You’ve done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir? At long last, have you left no sense of decency?” Although not a professional actor, the wryly charming Welch underlines the idea that all attorneys are performers.

Finally, in his first film, George C. Scott has terrific authority as Dancer, a skillful manipulator himself but ultimately undone by underestimating Biegler, in effect being fooled himself by the country bumpkin act.

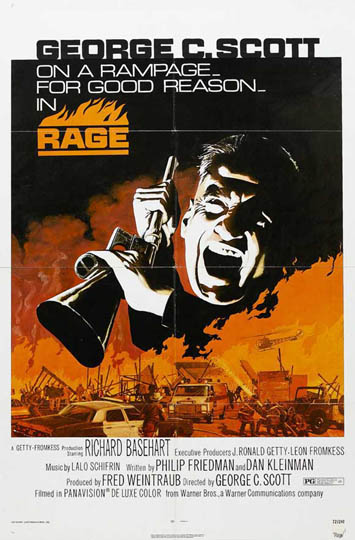

Footnote: George C. Scott’s Rage (1972)

And speaking of George C. Scott, a few years back Warner Archive released his feature directing debut, Rage (1972). I just came across a copy and saw it for the first time (I don’t think it got much distribution, at least not in my neck of the woods, when it first came out, though I did read co-writer Philip Friedman’s novelization back in the day).

Scott only directed two features, the other being The Savage Is Loose (1974), which I still haven’t seen, so perhaps like Marlon Brando (One-Eyed Jacks, 1961), it was something he found less to his taste than acting.

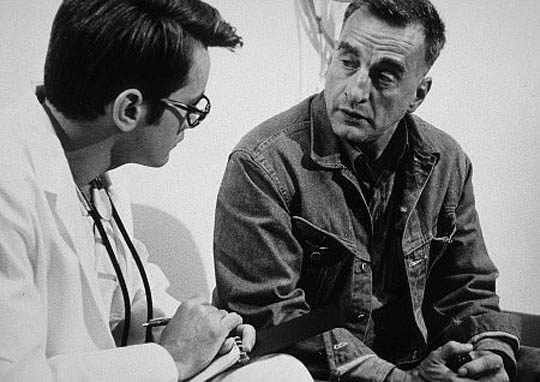

Interestingly, as with some other prominent actors who have tried their hand at directing (Brando and Mel Gibson, for example), Scott was drawn to a kind of masochistic, martyr story. In Rage, he plays Dan Logan, a Wyoming sheep rancher, a widower with a 12-year-old son. After camping out one night, he finds his son in a coma, bleeding from nose and mouth, and rushes him to the hospital. There’s obviously something a bit sinister about Dr. Holliford (Martin Sheen), the man who immediately takes charge of the case, shunting Logan’s family doctor, Roy Caldwell (Richard Basehart), aside.

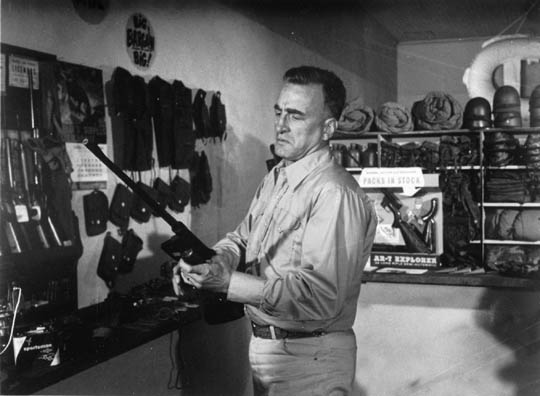

Logan remains passively trusting for rather a long time, although he’s kept from seeing his son. What we viewers know, but he doesn’t, is that he and the boy were accidentally sprayed with nerve gas when a test at the nearby air force base went wrong. (The story was loosely based on a 1968 incident in which a jet from the Dugway research station in Utah released VX nerve gas over Skull Valley, causing the death of 6000 sheep; a military report implicating the gas tests was written in 1970, but it was only officially released in 1998.) When Logan eventually discovers that his son has died and that he himself is also dying from the effects of the gas, he slips out of the hospital and sets out to get some kind of revenge.

The first time I watched the film, this is where I found myself frustrated because his actions are clumsy, unfocussed and eventually ineffectual. No sense of dramatic satisfaction. Only when I watched it again a few days later, taking into account its origins in the early ’70s, towards the end of the Vietnam war, at the height of distrust of the government, did the film make dramatic sense to me … no false Rambo-esque vengeance, just an ordinary guy trying to figure out what has been done to him and his son and wanting to strike out at those responsible. The fact that he never even gets close to the cold-blooded military men who have chosen to view the “accident” as an opportunity to study the effects of their new nerve gas on human subjects is an expression of the sense of helplessness and frustration people felt as they watched their government doing terrible things without caring about what ordinary citizens thought or wanted.

Rage ends on a chilling note of impotence rather than the kind of heroic triumphalism audiences got used to in the ’80s and beyond (Bruce Willis taking on ever larger armies of terrorists and criminals in the Die Hard series [1988-2007], Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger in countless action movies, Liam Neeson single-handedly destroying an army of Albanian scumbags in Paris in Taken [2008], etc.).

Scott’s determination not to make his protagonist too heroic results in a rather dull, methodically paced movie, although one which is more plausible and realistic than revenge thrillers to come. There are solid performances, though many scenes are purely expositional, and the only nods to an attempt at some kind of visual style are some fairly creative transitional effects, although because the film is shot in such a straightforward manner these tend to draw attention to themselves as mere editing tricks.

Comments