Background Detail

If I’m in a room talking to someone and there happens to be a bookcase nearby, or a shelf of DVDs, I become easily distracted from the conversation as I try to read titles to get some idea of the other person’s tastes and interests. A similar thing happens when I watch a movie: if there’s text somewhere on screen, my attention will go to it – signs in the background, the contents of a newsstand, the title of a book on a bedside table … and, of course, theatre marquees.

This is particularly interesting in movies from the ’40s and ’50s, when budget constraints combined with creative choices to make location shooting much more common. Movies shot in the streets of New York, say, offer a lot of documentary background which adds flavour and social interest to whatever story is being told. For a real movie fan, catching a glimpse of a favourite title or the name of a favourite actor on a poster or marquee in the background of a gritty film noir can add an extra little thrill.

Something like that happened just the other day when I was watching Michelangelo Antonioni’s interesting if not entirely successful second feature, I Vinti (The Vanquished, 1952), which consists of three short films loosely based on recent news reports involving crimes committed by young people, set in three different countries and three different cultures.

In the first story, a group of middle class Parisian students take a day trip to the country, intending to kill one of their number – partly to “punish” him for his seeming arrogance and partly to rob him of what they believe is a lot of money. As it turns out, after all his big talk, his thick wad of cash is phony, and the whole thing becomes depressingly pointless, the conspirators ultimately betraying each other.

In some ways, the second part, set in Italy, is both the most interesting and the least successful of the three. Initially, it was about another middle class young man determined to make a big political statement in the name of the workers. So he dynamites a factory, apparently killing a lot of workers in the process. Injured during the crime, he wanders about a grim city still under construction in the early postwar years, and eventually makes it home to his confused parents, dying as the police close in.

After the film’s premiere at Venice, where it was not well-received, this section was rewritten and new material shot to remove the “political” message. Now, the young man is merely an aimless opportunist involved in cigarette smuggling to make easy cash. A raid by customs agents ends with him shooting a policeman, after which he again wanders about for a night before returning home to die. As an exercise in radically altering a narrative while still using much of the original material, it’s quite illuminating (a bit like the horrendous Universal “love conquers all” cut of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil [1984], though less drastic); there are moments, particularly in the underground garage with his would-be girlfriend, where the new dialogue seems oddly out of phase with the character’s appearance and body language. The result ends up trivializing the narrative in order to make it less offensive to official Italian sensibilities. According to co-writer/producer Turi Vasile, Antonioni was perfectly willing to make these changes to appease the censors. (The original version is included as an extra on Rarovideo’s excellent disk.)

In the third story, set in England and in many ways the most conventionally movie-ish of the three, a blithely ambitious young man reports finding the body of a murdered woman in a park and sells his story to a newspaper. When his fleeting notoriety quickly fades, he tries to remain in the news by revealing more about the crime, until finally he confesses to being the murderer himself. When his trial ends with a death sentence, the newspaper’s editor is left with the depressing feeling that he, as a representative of the sensation-driven media, is at least partly responsible for the woman’s death.

There are hints in I Vinti of Antonioni’s later concerns and techniques (the French story might be an early sketch for the island section which opens L’Avventura [1960]; the English story, with its body found in a city park, is an obvious precursor to Blow-Up [1966]), and from what we know of the director’s obsessive attention to detail in his later films, we might suspect that anything in the frame has been put there deliberately. So, in the English story, when the young man walks out of a movie theatre where he has just met his apparently random victim, a rather sad and battered middle-aged woman reduced by necessity to prostitution, and Antonioni frames their brief conversation in the street with the theatre marquee clearly visible above them in the background … well, it doesn’t seem unreasonable to wonder about the significance of the show they’ve just been watching.

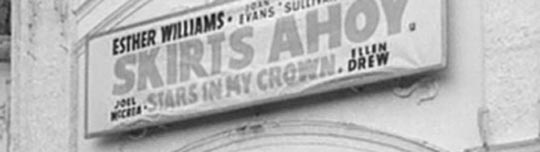

Although the town of Saffron in which the crime takes place is apparently fictional (while there is a small town in Essex called Saffron Walden, coincidentally only about twenty miles from where I was born, that doesn’t seem to be the film’s setting), the marquee bears the titles of two actual movies. Of course, this might just happen to have been the double bill showing in that theatre on the day that Antonioni shot the scene; but would he really have just left this detail to chance when he could have easily changed the signs to suit the purpose of the scene? So, if we suspect that the show the characters have just seen is of some importance, what might that importance be?

The headline picture is an Esther Williams romance called Skirts Ahoy (Sidney Lanfield, 1952). I admit I’ve never seen this, though it appears to be a routine, undistinguished effort. The second feature is Jacques Tourneur’s Stars In My Crown (1950). The slight difference in release dates needn’t mean anything; distribution back then was different from today’s obsession with getting a movie out to the widest possible audience immediately on release and burning off interest quickly before sending it to secondary markets; a movie could circulate for years, turning up as here at the bottom of a double bill, and there was no perceived need to pair films which had some kind of connection with one another. The seemingly random combination of an Esther Williams programmer with Tourneur’s exquisitely personal drama is quite plausible.

And yet I keep circling back to the idea that it’s unlikely that Antonioni would have left this detail to chance. Is it possible that he could be offering some kind of comment on the narrative and its themes?

The contrast between a vacuous Hollywood romantic comedy and the pathetic exchange between Aubrey (a chillingly cheerful Peter Reynolds) and Mrs. Pinkerton (Fay Compton), with her attempts to add a small note of romance to the commercial arrangement between them, is perhaps all rather obvious, a cruel irony.

But then, in smaller lettering, there’s the second feature, Stars In My Crown with Joel McCrea. If I’d watched I Vinti a few months earlier, this would have meant little to me. Although I’m a fan of Tourneur’s work, I only recently became aware that he’d made a number of westerns (a genre for which, intuition suggests, he would have had little affinity). I first came across Stars in a passing reference in Jonathan Rosenbaum’s most recent book, Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia (University of Chicago Press: Chicago and London, 2010), in an essay on John Ford’s The Sun Shines Bright (1953). What he said was interesting, so I ordered a copy of the Warner Archive burn-on-demand release, as well as tracking down a copy of Chris Fujiwara’s book on Tourneur, The Cinema of Nightfall (Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore and London, 1998). The film surprised me and the book, while Fujiwara sometimes goes overboard in his admiration of Tourneur (there are occasions when even a film’s flaws are “perfect”), revealed a body of work even broader and richer than the considerable achievements of the poetic Lewton horror films and Out of the Past (1947), the greatest of all noirs.

Stars In My Crown (based on a book by Joe David Brown, whose other novels formed the basis of Peter Bogdanovich’s Depression-era Paper Moon [1973], and Delmer Daves’ anti-racism war film Kings Go Forth [1958]) is the story of a war-weary man named Josiah Doziah Gray (McCrea) who turns up in the small town of Walesburg after the Civil War and establishes himself as the local preacher. The film is about the formation of community, the establishing of a peaceful society through the application of a firm sense of decency rather than at the more usual barrel of a gun.

There are two main storylines in the film. One involves an outbreak of typhoid which the young doctor Harris (James Mitchell) blames on the Reverend, towards whom as a “man of science” he’s hostile. But the other line, about a form of social rather than medical contagion, may be pertinent to I Vinti. Throughout Stars In My Crown, there is an escalating degree of violence directed by the local mine owner Lon Backett (Ed Begley) at an old black man, Uncle Famous Prill (Juano Hernandez), whose land sits on top of a rich vein of ore. Backett puts pressure on Famous to sell his land, but the old man stubbornly clings to what’s his. Eventually, Backett’s workers attack the farm (dressed in Klan-like hoods), first trashing the place and destroying the crops, then when Uncle Famous still won’t leave, returning to lynch him.

The Reverend steps in and insists on speaking to the mob, but not to prevent the lynching, rather just to make sure everything is in order before they do it. He holds up a paper which he proceeds to read from: the will he says he’s helped Uncle Famous draw up. One by one, he names each man in the mob and reminds him of some prior connection with Famous, leaving a small token in remembrance of that connection so that these killers will always be reminded of the old man they murdered. By the time the reading of the will is done, all the hate and anger have been shamed out of these men and no one has the stomach to carry out Backett’s orders. It’s only as they shuffle off into the night that Tourneur reveals the blank paper in Josiah’s hand; he has simply used his knowledge of the community, of each of its members, to remind all of them of the deep connections they have with one another, to force a recognition of their mutual humanity, which makes the intended act of violence impossible.

It’s that sense of community, of mutual connection and dependence, which is missing from the bleak little town of Saffron where the pathological egotist Aubrey commits his random act of violence without a trace of empathy or conscience. He simply can’t see the humanity he shares with his victim; she’s merely an object to be used to make a name for himself.

Of course, one of the great themes that runs through Antonioni’s work is the sense of emptiness that envelops people in a desolate world where that recognition, that sense of connection and community, has been obliterated by a materialistic modernism.

Was Antonioni thinking of this when he aimed his camera past his actors to that marquee? And if he was, could he expect that clue to mean anything to his viewers?

Maybe I’m reading far too much into this small detail, but the fact that it’s there forced me to think a bit more deeply about the story Antonioni was telling and made I Vinti – situated in both a realistic social world and a larger conceptual world – just that much richer for me.

Comments

The “Saffron” scenes were mostly shot in the Cheam area. The actual scene of the murder is a combination of Banstead Common and Banstead Downs Golf Club, which lie either side of the railway line seen in the film.